A tale of three ballets

‘Rama Hari’ (Alice Reyes Dance Philippines)

In 1979, National Artist for Dance Alice Reyes scored a coup when she assembled the country’s best talents to write the script and libretto, and translate and design the Pinoy musical “Rama Hari,” based on the Indian epic poem. In the four decades since, it recently held two successive reruns with live orchestras playing to packed audiences.

“Rama Hari” was in a different world when it was launched in 1980. Back then, a Filipino musical with contemporary movements and National Artist for Music Ryan Cayabyab’s scoring of ballads, pop, rock ‘n’roll, hard rock and kulintang was novel. The singing counterparts of the dancing characters have since become OPM icons.

Alice Reyes Dance Philippines’ production resonated with today’s audiences largely due to Cayabyab’s enduring and heart-tugging songs, written by National Artist for Literature Bienvenido Lumbera and translated into English by National Artist for Theater and Literature Rolando Tinio. The singing cast in the recent production, led by Vien King and Sheila Valderrama-Martinez, enthralled the audience.

Today, “Rama Hari” looked like a product of its time. The dance’s main style, a soft execution of Martha Graham, was injected with a hodgepodge of influences such as a Chinese ribbon dance, Indonesian puppet shadow play and jazz. The battle between Rama and Ravan via shadow play was anticlimactic.

The choreography could still be relevant if the dancers had the correct technique, movement dynamics, risk taking and, more important, the understanding of their characters—even if they were just the townspeople. The attack of the movements was too lightweight for an earthy dance genre. Most of the ensemble, borrowed from other dance groups, made the National Artist’s choreography look like a classroom exercise. The matinee leads, Ejay Arisola as Rama and Katrene San Miguel as Sita, lacked chemistry. Likewise, they could have been more interesting if they did research rather than looking cute on stage.

In the past, the stage design by National Artist for Theater and Design Salvador Bernal was grandiose on the cavernous stage of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. That same design was not scaled to the dimensions of Samsung Theater. Hence, everybody looked cramped onstage.

Still, there’s something about the romance, the enduring music and the innocent choreography that lured people to the theater.

‘Le Corsaire’ (Ballet Manila)

If Ballet Manila (BM) were an app, this company would have been the highly improved version. The principals and soloists are in their best shape ever as a result of strength training and artistic maturity.

Historically, “Le Corsaire (The Pirate)” has been an extravagant display of virtuosc and prolific dancing threaded together by a silly plot. Yet, it has become a perfect vehicle to show off BM’s consistency through the years.

Artistic director Lisa Macuja-Elizalde reworked the structure and injected some character development and dances to make the inane story seem logical while maintaining the major dances, choreographed by Marius Petipa. It took a while to distinguish stunning identical twins Jasmine Pia Dames as Medora from Jessica Pearl as Gulnara, Medora’s friend. Onstage, Pia’s dancing was marked by muscle control, sparkling confidence and well-articulated movements. She sailed across the Aliw Theater stage in broad sweeps and effortlessly embellished fouetté turns.

As Gulnara, Pearl matched her sister’s prowess on a lighter level. Pearl’s dancing power was softened by her inner fragility. She was most impressive in the balances and lyric movements.

Romeo Peralta as Conrad was a technically adept and sensitive partner, though a bit reserved for a pirate.

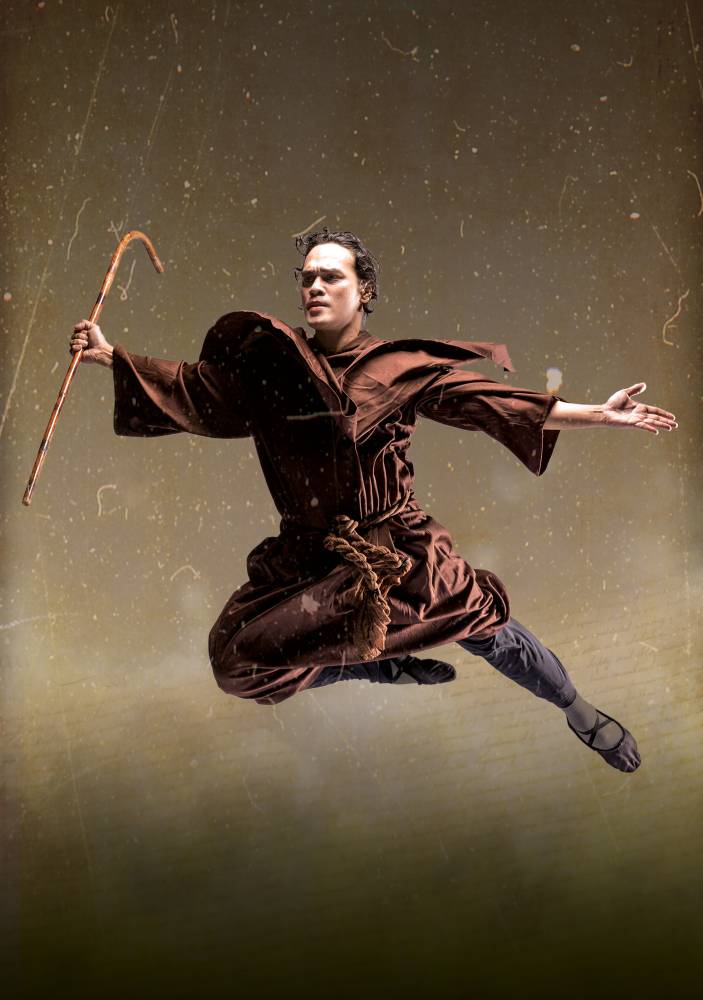

At age 42, Gerardo Francisco played Ali, whose solo is a favorite competition piece of teenage boys. Young dancers could learn from Francisco that great dancing is not about tricks. He impressed the audience with his suspended leaps highlighted by the lengthening of muscles, clarity of movement and hitting the music’s pulse in a thrilling manner.

Joshua Enciso has always stood out for a strong stage presence. As Birbanto, Conrad’s traitorous companion, he was sleek and brutish.

Among the three Odalisques, Sharia Comeros was close to perfection, blossoming in her upper body while her footwork was delicately flickering and weightless. Risa Mae Camaclang compensated for the lack of refinement with her raw energy and willpower. The unflinching Eve Chatal executed an inspired diagonal of triple and quadruple pirouettes.

The company’ strength is always determined by the corps de ballet. BM’s male ensemble always brought the house down with its testosterone-driven dancing, apropos of their pirates dance. In the Jardin Animé divertissement in Act III, the female corps members were well synchronized.

‘Limang Daan’ (Ballet Philippines)

How has colonialism turned the Philippines into a patriarchal society which oppressed the Filipina? Why did it take her five centuries before she could undress onstage and hold up her fist? This seemed to be the premise of Ballet Philippines’ 54th season-ender at the Theatre at Solaire.

Written by filmmaker Moira Lang, “Limang Daan,” filled with historical references, presented Filipina archetypes—the harassed nurse, the sexually repressed nun, the demure bourgeoise Maria Clara, the objectified Igorot and the transgender as the babaylan.

The slick production design, replete with moving sets by Emilio Infante and LCD projection and costumes by fashion designer JC Buendia, made “Limang Daan” look expensive. But the choreography by BP artistic director Mikhail Martynyuk left us with questions.

On the plus side, we could now understand his choreographic intentions. Thanks to his coaching, BP company became better movers, although the dances didn’t give them much motivation to be emotionally involved.

A weak spot was the lack of tension between the antagonists and protagonists in the vignettes.

Then there was the awkward pas de deux between Crisostomo Ibarra and Maria Clara, wherein the partner made her look heavy in the overhead lifts. The scene stealer was Peter San Juan, as Padre Damaso. Still, the audience had no idea why he was emoting.

We were further bemused in the Chico Dam scene which referenced the resistance to Marcos’ project. When the government forces stacked large boxes on the set, the audience wondered what was their function, which was never revealed. The choreography of the square off between the Kalinga women and the government forces was inconsequential until the leader Buwaya was stabbed.

One of BP’s weak spots is the lack of diversity of viewpoints. All the choreographies are made by one person who is more of a mentor and a classicist than a choreographer.

Is there a problem with inviting a guest choreographer or inspiring emerging choreographers from the ranks to offer a little variety? —CONTRIBUTED INQ