An artist’s ode to fisherfolk and the sea

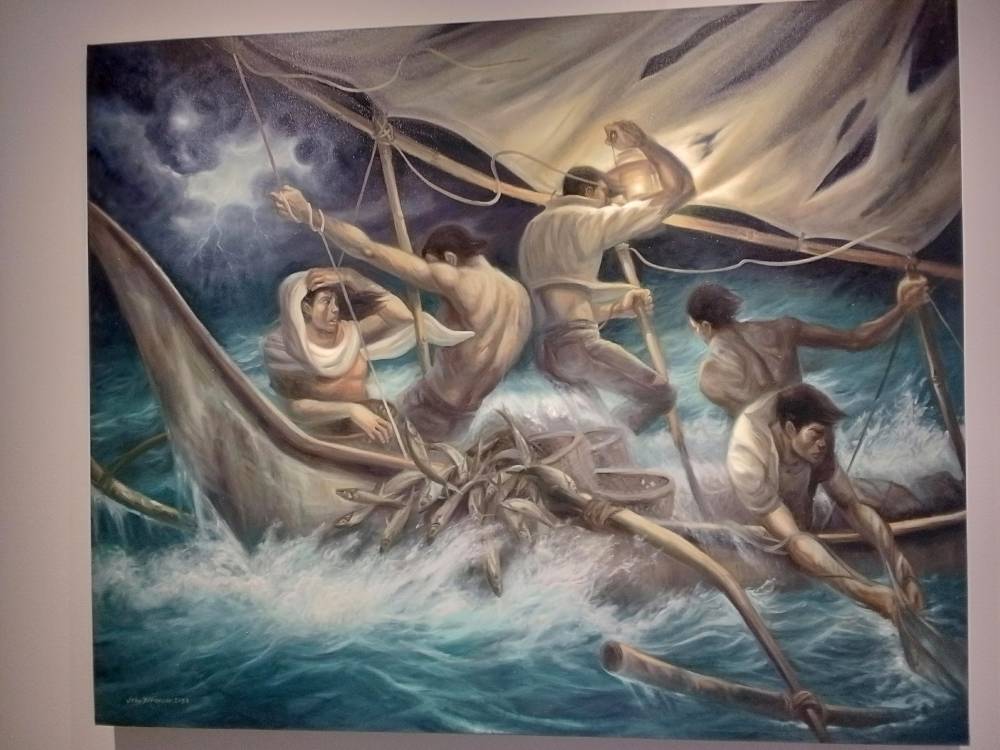

The images are powerful, fisherfolk against the sea. We see fishers and their families struggling to earn a living in storm-tossed waves, and as the sun sets. The women are no maidens in distress; they are strong and share the hardships of the men, and so do the children. Nature is threatening, and tension is in the air.

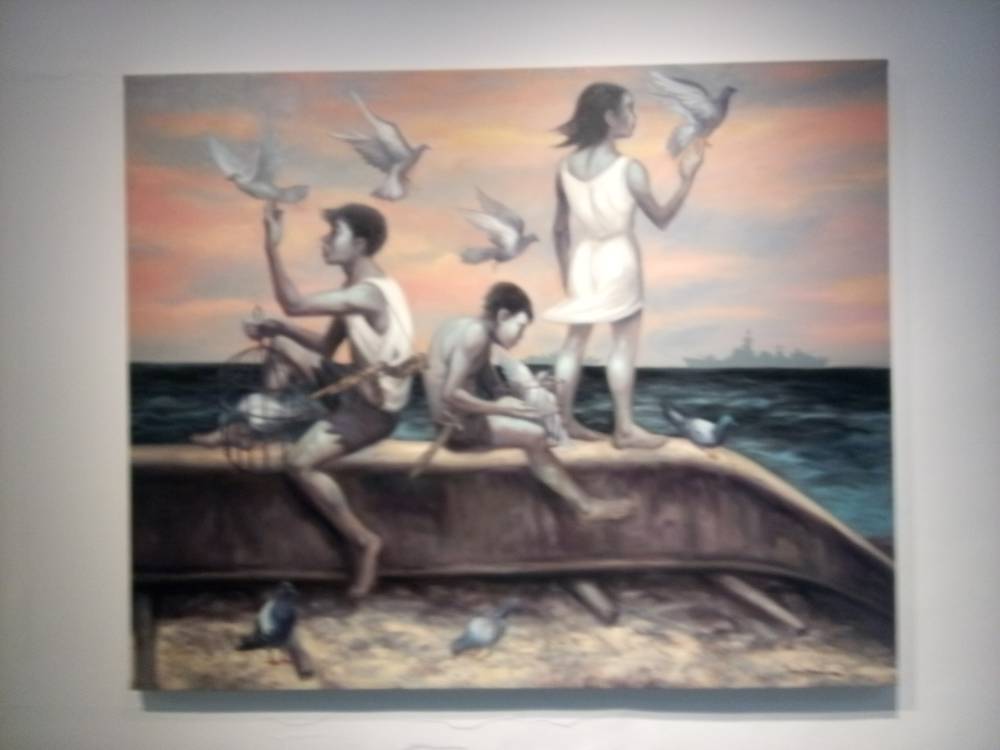

There is only one painting (“Hayon sa Lirip”) which can be called typical and peaceful. Three children are on an overturned boat playing with the birds flying around. The sea is calm now, and there is a ship in the background.

These are some of the impressions one gets while viewing the solo show—his 26th—of Jeho Bitancor, titled “Sa Dalampasigan ng Daluyong at Dalangin,” at Art Cube Gallery, Makati City (tel. 88167758). The exhibit runs until Oct. 5.

Bitancor’s art has evolved through the decades, from what he called quasi-surrealism, social realism, some kind of expressionism and finally back to social realism with a vengeance. The artist hails from Baler, Aurora, a historic coastal town facing the Pacific Ocean, which is why he can interpret the sea with gravitas.

Martial law baby

A martial law baby, Bitancor majored in Painting (minor in visual communication) at the University of the Philippines, Diliman, during the 1980s; the campus was in turmoil. “I discovered social realism,” he said.

Another talent lay in Tagalog poetry, although he was not sure about his academic qualifications here and passed up the chance to hone his ability, including a Rio Alma clinic.

Flash-forward: In 1997, during his second solo show at Liongoren Gallery, Bitancor used his own verses to accompany his paintings on display. One of the visitors was poet Pete Lacaba (a Gawad CCP awardee). So he asked the poet, “Sir, pwede na ba ang tula ko (Does my poem pass muster)?” Lacaba’s reply: “Kung ako ang editor, isasama ko ang tula mo sa libro (If I were the editor I would include your poems in the book)!”

He may not have made it as a poet but the literary influence remains strong in Bitancor, as evidenced by the title of his current exhibit at Art Cube, with its imagery of the seashore, storm surge and prayer.

Rush hour

The artist’s first solo show, “Takipsilim” (Dusk) was in 1995, with the sponsorship of the Art Association of the Philippines (AAP), then headed by eminent glass sculptor Ramon Orlina, who liked Bitancor’s work. His paintings were inspired by the chaos of rush hour in the metropolis, with overloaded buses and jeepneys, beer gardens starting to be filled with drinkers, and people hurrying home.

“So I captured all this, the traffic, the commuters,” he recalled. “There were a lot of subjects, people going up and down the stairway, Quiapo underpass, the flyovers, you could see they were tired, hurrying to catch a bus or a jeepney. As a worker myself, I hated that experience, hurrying, hurrying, hurrying … ”

After his second solo show in 1997, another prominent figure gave him a break. Art critic Eric Torres, then curator of the Ateneo Art Gallery, recommended him for a grant being offered by the Vermon Studio Center in the United States. He was accepted, the only two from Southeast Asia. The other was sculptor Julie Lluch (another Gawad CCP awardee), who unfortunately could not make it for some reason.

It was a good experience for Bitancor, for there were other young artists from around the world. And they worked undisturbed for three months.

When he returned to the Philippines, he resigned from his job as an advertising art director, and became a full-time visual artist.

His current show pays tribute to the fisherfolk, but it is more than that. Lurking in the background is the artist’s political consciousness in the wake of the headlines over the West Philippine Seas issue.

“They are heroic,” says Bitancor of the fisherfolk he depicts. “They risk their lives in the sea just so they can have food on the table. Their work is more honorable than you politicians, you businessmen. And now their livelihood is being threatened by China.”

For this artist, art should be in the service of society (“may silbi sa lipunan”). No art for art’s sake for him.