Balletcore, but where are the ballerinas?

Designers are increasingly treating fashion as a form of performance, where garments come alive through bodies, movement, sound, and narrative. Take, for example, Willy Chavarria’s Fall/Winter 2026-2027 Paris show, which transformed the runway into a Broadway-style cinematic tableau. Music, theater, and fashion merged seamlessly. Models moved slowly, almost choreographed, through vintage-inspired silhouettes, such as low-rise tailoring, oversized jackets, and cocktail dresses—transforming the presentation into a deliberate, performative experience.

Similarly, at Paris Haute Couture Week Spring 2026, Gaurav Gupta treated fashion as wearable sculpture. His collection relied on philosophical storytelling, transforming garments into moving artworks that were as much narrative as it is ornamentation.

Both shows highlight fashion as performance art—where meaning emerges only when the body inhabits the clothes.

Taking the ballerina out of balletcore

Balletcore endures because it captures a unique intersection of aesthetic and emotion. The trend isn’t just tulle skirts or satin flats; it’s also about the culture of femininity, discipline, and grace. Balletcore translates the language of ballet into clothing—a skirt swishing, a shoe pointed, a posture extended—allowing anyone to participate in a performance, but in fashion form. This is why the question of who wears the clothes matters.

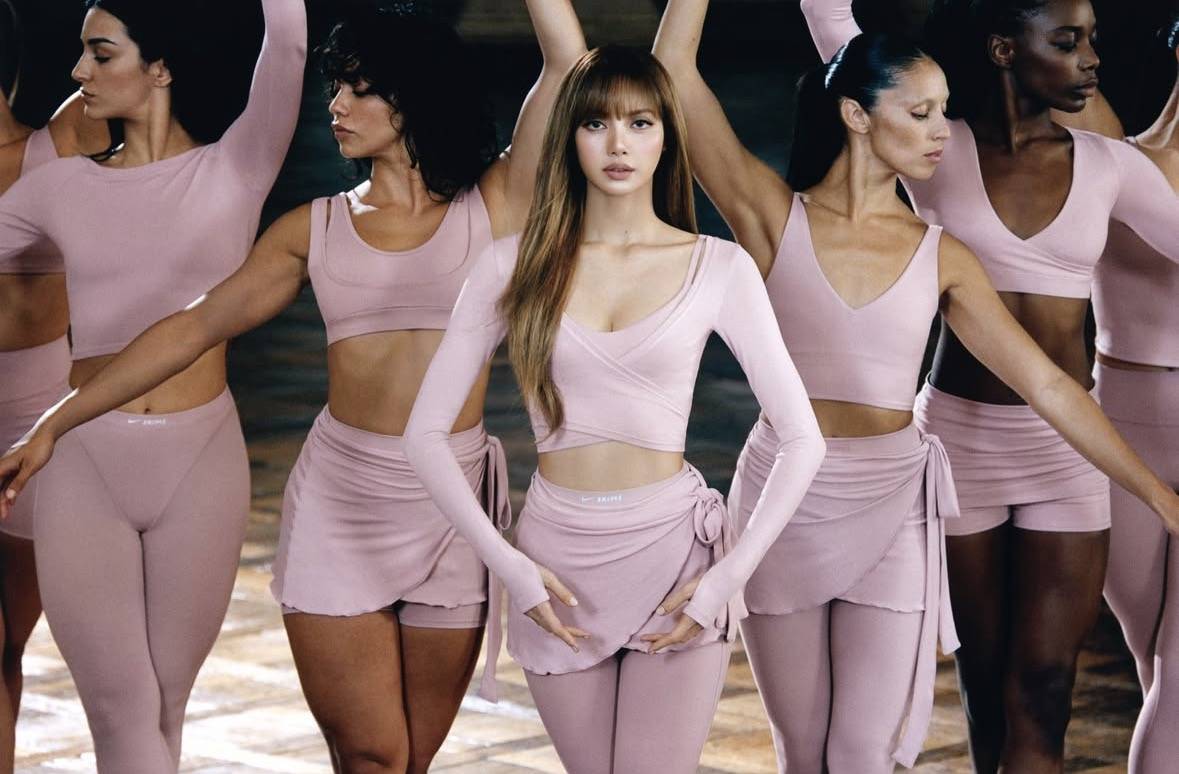

Recent attention around the Nike × Skims Spring 2026 collection featuring Blackpink’s Lisa illustrates this perfectly. The campaign leans into ballet-inspired imagery and choreography yet instead of hiring a trained ballet dancer, it stars a globally visible pop icon.

People argue that while Lisa’s presence brings attention and energy, she does not embody the technical discipline of ballet. Yes, fans defend the campaign, citing Lisa’s dance skills—but much online commentary highlights a tension: If balletcore is about movement, femininity, and grace, then why isn’t the person performing ballet trained in ballet?

Choosing a famous face over a trained artist

Instagram users and Reddit threads have pointed out that the choreography reflects basic gestures rather than true ballet technique. Meanwhile, ballet dancers pointed out the irony of Skims invoking ballet’s physical language without employing the people who practice it.

This critique extends beyond Nike × Skims. Past balletcore-inspired collections—from Miu Miu’s satin flats and pastel corsetry to Christian Louboutin and Reformation dropping ballet-inspired pieces—did not feature trained dancers.

Brands like Selkie, however, prove that it can work. Hiring ballet dancers for a balletcore campaign, Selkie received overwhelmingly positive feedback for bringing real movement literacy and aesthetic to fashion.

Why do brands keep doing this? The answer lies mainly in economics and visibility. Celebrities like Lisa bring instant global buzz and guaranteed media coverage—that’s good for clicks and sales. Ballet dancers, even acclaimed professionals, typically don’t have mass-market star power outside of dance communities.

And from a marketing perspective, a famous face is easier to sell than a trained artist. However, that alone does not justify why Lisa deserves to be the face of this collection, even if she is also the brand’s global ambassador.

Why it matters

The issue isn’t about representation. It’s about the meaning of performance in fashion. If fashion truly sees clothing as a vehicle for lived experiences—as movement, body negotiation, and emotional expression—then hiring ballet dancers shouldn’t be optional. It should be strategic.

Fashion often co-opts ballet’s visual language but rarely honors the labor and expertise behind it. If balletcore is here to stay, brands need to align image with expertise. At a minimum, hiring trained dancers in campaigns would honor the discipline that gives balletcore its meaning.