Bambi Mañosa-Tanjutco: Dream peddler

Bambi Mañosa-Tanjutco held many job titles in her life: toy quality tester, interior designer, artist, and teacher. But in her role as Museo Pambata president for the past six years, Mañosa-Tanjutco could also be called a dream peddler.

For what else could she be? From the moment she became president of the museum in January 2019, all she did was make phone calls, set up meetings, and rally people, including her family and friends, selling dreams and visions to save the Philippines’ first children’s museum.

Her late father, National Artist for Architecture Francisco “Bobby” Mañosa, convinced her to join the Museo board.

“He went, ‘You start with little kids. Teach them to love our country,’” she recalled. “On his deathbed, I said, ‘Dad, you’re leaving me now. You wanted me to come on board Museo. I’m going to be there now. Better send me the right people from heaven.’ And for some reason, the right people just fell into place.”

Museo Pambata first opened its doors in 1994, housed in the historic Elks Club Building on Roxas Boulevard. The City of Manila granted the museum free lease of the land and building, but when Mañosa-Tanjutco signed on, the lease was ending. The board was already looking into other places that could be the Museo’s new home. But she refused to give up.

Reimagining project

Mañosa-Tanjutco’s first task was to have the museum’s free lease extended. After a talk with the local government, she succeeded in securing another 25-year lease. That extension became the foundation on which she began to reimagine the museum’s future.

But then the pandemic struck, and the threat of closure returned. Like everybody else, she thought the lockdown would only last for two weeks. When they realized it would be longer, the lockdown presented an opportunity to fix the building and update the space. But the museum had no funds. They were forced to retrench employees because they no longer had the means to pay salaries. From 45 people, the staff was trimmed down to three.

Mañosa-Tanjutco took a month off from the board, away from the “adults.” She tapped her daughters and Kids for Kids founders Bella and Tasha Tanjutco to brainstorm with her.

“I worked with young people, reimagined. And when you start listening to them, there’s so much hope. And there’s a dream. So it gets you, it fuels you. [I told myself that] this was now a reimagining project,” she said.

Then the Makati Development Corp. offered to manage the project for free. Supported by her childhood friend and Museo vice president Sofia Elizalde, they were able to meet with suppliers and present their plans via Zoom. She successfully received discounts on Museo’s behalf.

Learnings

But Mañosa-Tanjutco didn’t stop there. Her family also pitched in to help.

Her architect brother, Gelo Mañosa, suggested a lot of things, which included tucking the fire staircase into a corner so they could make use of the space as an open area. He also suggested the Bahay Kubo 2.0 feature in place of the greenhouse. The 2.0 is traditional on the outside, but modern Filipino in its interiors. Mañosa-Tanjutco herself designed the space with Milo Naval’s furniture.

She mobilized volunteers and convinced many people to join her in saving the Museo. She remembers all of them: her classmate who specializes in pools created the pond under the Bahay Kubo; her father’s friend who donated P8 million worth of air conditioning; and the artists who shared their talents to make the walls of the Museo come alive with colors.

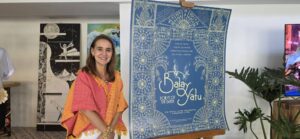

The condemned annex building wasn’t fit for people, but it’s not in Mañosa-Tanjutco’s genes to give up on structures. Her daughters, who also founded Tayo Philippines, reimagined it as a space for teens and young adults—and they worked on it. It is now called Balay Yatu, a spacious building for events and exhibits.

The playground makes use of her father’s beehive design—something she had to dig up from his archive.

“So every space actually has learnings. Bahay Pukyutan is all about the geometry of space, value of small ecosystems, inclusion, and community,” she said.

National Artist for Film Kidlat Tahimik and artist son Kabunyan de Guia also lent their hands to the Museo because of her convincing. De Guia worked on the mosaic of the Bahay Kubo, while Tahimik loaned some of his pieces to the Museo.

Artists Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan have their own room on the second floor. Their massive cardboard community encourages children to create their own pieces and leave them there to join the others. Mañosa-Tanjutco says this room is her happy place.

The Museo, for all the beautiful updates it received under Mañosa-Tanjutco’s leadership, remains child-friendly. If an area in the Aquilizan room gets accidentally flattened, it will simply be rebuilt.

Grand gestures, quiet details

Mañosa-Tanjutco’s contributions to the children’s museum come in both grand gestures and quiet details. Her fingerprints are on the wrapped trees outside the compound, which serve as markers that catch the eye of passing motorists. It’s also in the ROYGBIV-defying rainbow at the floor entrance. It’s a deliberate message to encourage those who enter to create their own rainbows. In the same area, one could find the gigantic jackstone pieces, which she got for free from a mall after asking for them.

It’s in the lighting along the hallway, thoughtfully positioned to reveal the beautiful scenery painted on the walls. Her experience as an interior designer and artist gave Museo a more cohesive, inviting atmosphere because every space is thoughtfully utilized.

Perhaps one of the most understated improvements she made is the space for adults. There are now seating areas outdoors, which allows parents to pause while kids explore and play on their own. A simple solution to make families stay longer.

There was excitement in her voice when she gave this writer a tour of Museo. She acknowledged the efforts of those who made it happen. She touched the displays lovingly, closed the doors carefully, and smiled broadly when she saw children enjoying the things she worked hard for.

At some point, we stood together in a relatively empty area outside Balay Yatu, facing a door that leads to a storage room.

“The idea is to have a hub out here, so then it could be an outdoor library. It would be like entering a forested area. It would feel like Narnia,” she said animatedly, her eyes twinkling.

And there, in all its emptiness, this writer allowed her words to sink in—and saw it, too, and found the vision beautiful. This is Mañosa-Tanjutco’s power. She inspires hope for better spaces for children—a true force of nature.

Mañosa-Tanjutco’s stint as president ended last January. She served two terms back-to-back. For now, she is working on her father’s book about the Coconut Palace.