Celine Lee stitches the human in a world of code

When an artist turns to an analog process to contemplate digital spaces and experiences, the result can be a meditation on the very nature of perception.

In Celine Lee’s hands, the act of stitching—an additive gesture as ancient as the human story—becomes an assertion of the human presence amid the pixelated and the programmable. Each thread resists deletion, insisting on touch in a time defined by screens.

What it means to be human

Lee’s solo exhibition “Through” at MO_Space, is a visually riveting inquiry into the intersection of the analog and the digital. It is a series of works that thinks as much as it feels, with a visual language that moves fluently between precision in craftsmanship and conceptual depth—a reflection on how the handmade might still map meaning in a world increasingly drawn in code.

Her work also gestures—albeit tangentially—toward the tension between the utopian and the dystopian currents of contemporary life. By posing an existential question about human agency amid the rise of artificial intelligence and the relentless march of scientific advancement, Lee invites viewers to reflect on freedom itself: what it means to assert one’s will in a world where change and “progress” are the only constants.

In more ways than one, she urges viewers to question their own ways of seeing—their visual perception, conceptual judgment, and philosophical and social moorings. Who are we, she seems to ask, in a world that is drifting ever more rapidly toward the unknown? And can we still make a difference within what often feels like a carefully engineered system—a matrix of power relations, artificial intelligence, and vested interests—that continues to redefine our understanding of what it means to be human?

What lies at the core of your distinct visual language and multidisciplinary practice?

From a very young age, I’ve already been confronted by the thought of “nothingness.” For most of my life thus far, I’ve been someone who has constantly felt the liminality of being. I’ve learned to sit through these thoughts through my artmaking.

These existential thoughts have informed my practice by grounding it in science while trying to navigate the psyche. They have led me to question and/or mirror pre-existing concepts and systems in order to gain a better understanding of them and, hopefully, provide a different perspective on them. I think that artists are actually “masters” of the liminal space because they constantly traverse thought and form, so that’s exactly where I ought to operate from—to be my own medium.

Can you walk us through the ideas and process behind your solo exhibition “Through”?

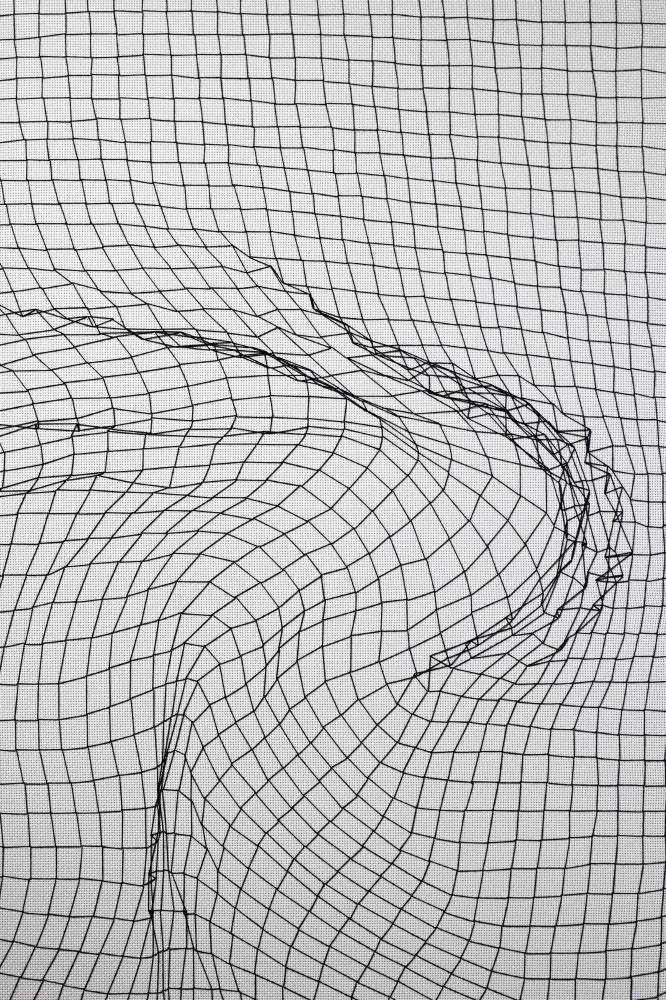

I started using Aida cloth back in 2017, initially using the material to represent the “fabric of spacetime”—ironically so, because the idea was to represent something that was “unseen.” The Aida cloth, which is typically used in cross-stitching, resembled a Cartesian plane, consequently becoming this metaphorical world map.

Eventually, the series of works on Aida cloth has solely relied on the wireframe imagery, generated through a 3D software called Blender. I think that “world-building” is innate in using such tools. So, combining the processes together to create embroidered pieces on Aida cloth adds to the ontological layer of the series itself. When did the image or form become “some thing”? Was it when the code displayed it on screen, or was it when I embroidered it?

For “Through,” I wanted the viewers to feel the temporality of the work more than anything. In the process of making the work, there have been these “unseen forces” that have come into play, and that is the whole point of the exhibition.

You have spoken about the notion of agency—what human beings can and cannot do. What draws you most to this idea of agency, and how does it shape your work?

I’ve mentioned being grounded by science, but sometimes I think it diminishes this idea of one’s “agency.” For example, in neuroscience, the so-called Libet experiment found that there’s brain activity hundreds of milliseconds before a human is consciously aware of a decision to move. In genetics, a part of who you are isn’t just because of your personal experiences but also your genetic makeup. I think these speculate on the idea of free will being an illusion, and I find that quite interesting.

I feel that perception precedes perspective when viewing art, and that’s why I’m drawn to making works that demand perceptual attention. I think it forces viewers to engage with the work. This interaction is the point of my art practice—to question what they see, how they see it, and why they see it. The autonomy that comes with creating a work and showing it to others is potent.

In a way, I’d like for the viewers to question this very notion of agency with me.

Your relationship with materials seems deeply philosophical. What is it about specific materials or modes of production that speaks to you most?

I think every little thing holds meaning, or at least, reason. I consider my use of different materials as visual cues that already explain themselves to a certain extent. They already mirror a fraction of the world, so it’s interesting to be able to create another simulacrum out of them.

Additionally, different modes of production give room for me to experiment, and I think that trial and error and problem-solving keep my mind occupied creatively.

As one of the more established millennial artists working today, what would you say to those aspiring to become full-time studio artists?

I want them to ask themselves: “Ano ba ’yong ‘art’ para sa akin?” I think whatever their answer to this question is will say a lot about their intentions and aspirations.

If their answer to this question is clear, then good. If it’s unclear, I think they should be ready to face faltering. I think it’s more important to remember why you’re doing something rather than to know what you’re actually doing.

Maya Lin once said, “If we can’t face death, we’ll never overcome it. You have to look it straight in the eye. Then you can turn around and walk back out into the light.” If you were to leave us with a statement that captures your own artistic core, what would it be?

The way out is through.

Finally—why are you an artist?

Because I’m human.