‘Decolonizing’ the kitchen: Lessons in growth and leadership

This year has been one of change and introspection. It made me rethink my career path, the direction I wanted to take, and more importantly my worth as a chef and a woman.

In an increasingly celebrity-driven industry, having a restaurant to call my own was very important, though in my case, it wasn’t really mine. I was trying to make it my own while listening to what others expected of me as a “French-trained chef.” Metronome was a tough balancing act, but I can proudly say that I did it well.

Was I really happy, though?

Metronome made me think of my situation as a woman in a professional kitchen: how societal gender roles have been so ingrained in me, how I’m supposed to put what others think and expect of me first, how to approach that with grace and gratitude, how to smile and make sure everyone else was happy with what I was doing.

I feel Filipino women do this naturally because it is expected of us. We are strong, we take charge, hold positions of power, are given opportunities, are educated, and are encouraged to have careers and earn our own money. On the other hand, we are also expected to nurture, appease, and put others first because we are still mothers, daughters, sisters.

Identity

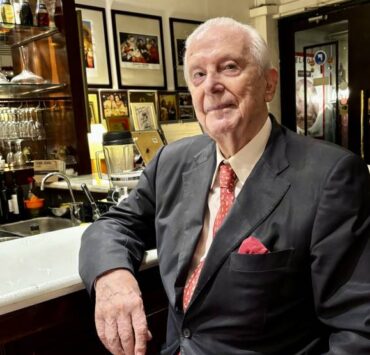

When I had a chance to step away and start fresh, I told myself to shut out other people’s expectations and cook the way I really wanted to. Yes, I had studied classic French cuisine at École Gregoire Ferrandi Paris, worked for Joël Robuchon for seven years, and lived and worked abroad for almost a decade. But these are just facets of my whole identity as a cook.

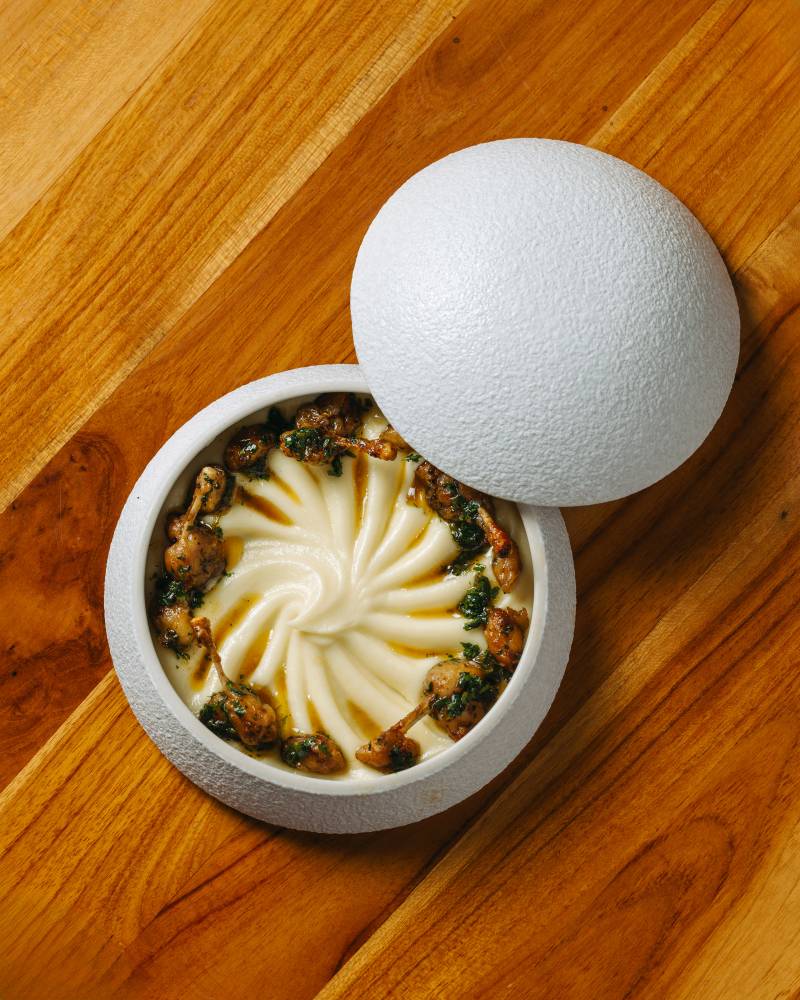

I am Filipino, first and foremost. I learned how to cook in family kitchens in Butuan City, where I was born. How I experience and study food will always be tied to my identity and experience. So when I use local ingredients or play with textures and flavors, it will never be classic French because that is not my life experience. I learned the technique, but how I cook is through my own experience.

This, for me, is my way of decolonizing the professional kitchen; that is, through a thoughtful and disciplined way of echoing my experience and identity. The idea that Filipino ingredients, thoughtfully deployed, could be made into dishes to equal French cuisine in refinement and sophistication can only enrich and vitalize the restaurant industry as a whole.

Representation matters

This residency at Makati Shangri-La was a personal “glass ceiling” I have broken. To say that it was a great opportunity for me is an understatement. For Filipino chefs to get recognition from a hotel such as the Shangri-La means we can cook as well as—or even better than—any of the chefs imported from abroad. If more hotels could recognize local talent like the Shangri-La did, the local dining scene would look very bright indeed.

This year allowed me to revisit what I set out to do for myself. I met so many people and so many young female cooks along the way. This has reminded me of how much representation matters. I was very fortunate to have had a strong, uncompromising woman in my Tita Susan (Calo Medina) to guide me through my formative years.

I was also fortunate to have witnessed, albeit from the sidelines, other female chefs carving out a career for themselves in the restaurant industry: Glenda Barretto, Myrna Seguismundo, and Margarita Forés. Because of these pioneering women chefs, I became convinced there was space for me in the culinary scene—local and global. I would also like to be able to set a tone for the young female chefs in return.

Yes, my 2024 was a roller-coaster ride, to say the least but I’m grateful for it. —WITH A REPORT FROM MARC MEDINA