Defining freedom: PH makes historic debut at 15th Gwangju Biennale

Since the Gwangju Biennale’s inception in 1995, the South Korea-based large-scale international festival of contemporary arts has featured a few Filipino artists, including Mark Salvatus in 2018. For its 15th edition, which opens on Sept. 7 in various locations around Gwangju City, the Biennale will have the Philippines’ own pavilion and exhibition, titled “Locations of Freedom.”

Multidisciplinary artist and curator Avie Felix has been tasked to put together the project. At the recent media launch for “Locations of Freedom,” she recalled that she got very excited getting the invitation in November because “curating in commercial arts for 15 years, it’s always hard to present the progressive work,” such as injecting social awareness.

The people behind the Biennale, she explained, “welcome progressive ideas” and “respond to the idea of revolutions,” Gwangju being the site of the 1980 uprising against South Korean dictator Chun Doo-hwan. Right away, Felix thought of like-minded artists who would join her in the lineup: Adjani Arumpac, Sari Dalena, Toym Leon Imao, Dennis “Sio” Montera, Paul Eric Roca, and Veejay Villafranca, plus Karl Castro as designer.

But Felix hesitated, as she and Montera are both with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA). She is an officer of the executive council of the National Committee on Art Galleries, while Montera heads the National Committee on Visual Arts.

Thus, asking for funding of a project outside the NCCA would pose a conflict of interest. Still, they agreed to fly to South Korea in December to meet the Gwangju Biennale’s organizers. Around that time, they decided they would take up the challenge of self-funding the endeavor and, by January, they officially accepted the invitation.

Felix got support from vMeme Contemporary Art Gallery, Fundacion Sansó, Imao Studios, the University of the Philippines Film Institute and the Philippine Embassy in South Korea, in addition to the funding from the Gwangju Biennale Foundation.

She and her team have also started a fundraiser to shoulder other expenses, such as the shipping costs of artworks, production and printing of catalog, airfare, accommodations and local transportation. Some of their artworks had been replicated into prints and can be purchased, along with “Locations of Freedom” shirts and mugs, at Fundacion Sansó in San Juan and through the museum’s website (fundacionsanso.shop). The exhibition runs until Dec. 1.

Act of resistance

Born a few years before the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution, Felix said she could connect that act of resistance to the revolution that’s been happening inside her. She explained in a mix of Filipino and English, “There’s anger, there’s a desire to break free from everything … Because there are so many things that you have to fight as a woman in a Third World, in Manila. I’m also a single mom.”

That yearning to express freedom is shared by her fellow artists, whom she described as contemplative and similar to philosophers. “Presenting a national identity is very tricky,” she said. “The artists I’m working with are truthful and authentic and really honest with their work. It’s very clear in their practice. I knew the show was already complete when they all said yes.”

Imao, likewise a human rights advocate, shared his thoughts at the launch of “Locations of Freedom.” He said in Filipino, “The meaning of our participation in the Biennale is that we value freedom of expression in our country, and we want to assert it. The Biennale is the perfect setting. It has a larger audience and there’s a discourse, not just noise…That’s why this group was created, and we’re not given an instruction manual on what to do, rather how to present the Filipino narrative in a global audience.”

Castro, for his part, told Lifestyle, “Freedom is based on justice, dignity, equality, and until we see that, in terms of how people live, how our cities work, and how our lifestyle is shaped and our policies, we don’t have freedom…I think in my own work, I try to pursue that. I make works on very political topics and also very personal topics. I also enjoy working with communities in a collaborative way to make art. I work with indigenous communities, veterans of martial law, and other communities.”

Remembering the disappeared

For the Gwangju Biennale, Imao is presenting two installations: “Desaparecidos” and “Debugging.” He described the first installation as an “old work,” dating back to 1972, when citizens considered dissidents by the martial law government mysteriously disappeared.

The artwork consists of sculptural figures made of resin and fiberglass that have, over the years, grown to the current tally of 53. The figures carry empty frames that cut through their bodies to “symbolize emptiness” and underscore the theme of of “remembering the disappeared and memorializing absence.”

Imao’s second installation is composed of seven life-sized figures, all women, who sit on a spiral staircase while hunched over, from the grandmother to the granddaughter, for the age-old practice of pagkukuto (removing head lice). In this scenario, though, each figure’s cranium is exposed to express the idea that “every generation has to weed out the lies perpetuated within their particular era.”

Filmmakers Dalena and Arumpac will showcase moving images that show a “parallelism of the historic and the mundane.” Dalena said she dedicates her artwork to the women whose pivotal role in history is being obliterated, from the comfort women during the Japanese occupation to beauty queens-turned-activists of the martial law era.

Arumpac, on the other hand, did interviews with some people from Marawi City about their experiences during the siege in 2017.

Importance of memory

Roca’s painting, “The Paradise of Unfulfilled Promises,” is patterned after 16th-century artist Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights.” He said his triptych has a narrative about the Philippines’ historical events, including martial law, with an allusion to cinema, because movies were used to entertain and divert people’s attention from what was really happening in the country at that time.

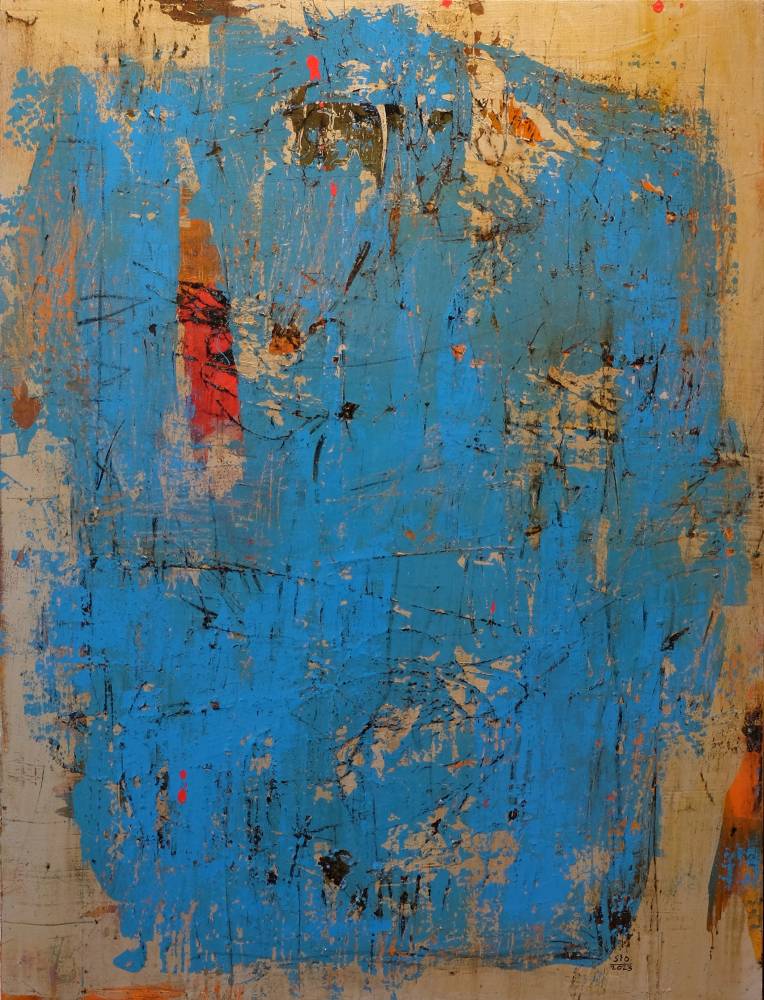

Montera came up with a mural-sized painting to illustrate “unlearning, uncloaking, dismantling illusionary paradoxes of belief through peeling off layers of paint.” It also turned into a geographical map featuring the different lines created by what is being contested now in the West Philippine Sea, causing tension around the region and beyond. He correlated this to having “anxious feelings of losing his blissful moments” at sea and his connection to the islands, particularly in his hometown in Cebu.

Villafranca’s photo montages, which were extracted from years of documenting daily life, turned into “visual journals of how the everyday lives of Filipinos bear witness to the everyday revolutions stemming from various challenges in the post-colonial contemporary Philippines.”

From there, he produced an installation that looks like a big scroll from a very high vantage point “to emphasize the importance of memory and how we seem to forget, even though images are already in our faces.”