From failing student to school founder

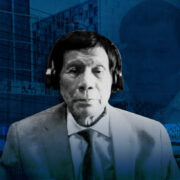

Fr. Rogelio B. Alarcon, O.P., education reformist and founder of Angelicum School in Quezon City (now known as University of Santo Tomas Angelicum College and my alma mater), was born on Oct. 26, 1937, in Laur, Nueva Ecija. His father was a doctor in the Armed Forces of the Philippines. Because of his father’s work, they had to transfer along with him to the various places he was assigned.

Alarcon started kindergarten in the middle of the Japanese Occupation. He studied in the garage of his neighbors. In second grade, he transferred to Sta. Catalina College in Legarda, Manila, and then spent Grade 3 in the evacuated setting of Sta. Teresa, since the San Marcelino school was occupied by the Japanese.

His schooling was interrupted once more during the battle for the Liberation of Manila. After Liberation, he and his family moved to Baguio City and Alarcon enrolled at St. Louis University (then St. Louis School) as a Grade 4 student.

Pupils attended classes in tents and they had only a few textbooks which had been saved from the war. He stayed at St. Louis until fifth grade before moving back to Manila. Alarcon and his family lived in Tondo, and he went to Letran for sixth grade.

He remembers his early days in Letran, saying in Filipino, “My classmates knew a lot more than I did; they were skilled in reading, arithmetic and other subjects. I couldn’t understand anything because I kept moving schools. My grades were … line of six,” he said.

He ended up repeating sixth grade and then staying in Letran until he graduated from high school. After, he would study at La Salle College of Engineering, but after one year, he felt a different calling—that of the priesthood. He entered the postulancy for the Order of Preachers, the Dominican Order, in San Juan.

After being accepted, he was assigned to the elementary department of Letran. The Dominicans had returned him to the place where he had failed in his studies or, in his words, “lumagpak.”

Blaming the system

While he was assistant principal, Alarcon observed some sixth graders failing, just like he did when he was their age.

He said in Filipino, “Of course there were students who were having a hard time with their studies. They had their own problems. When I saw that, I said to myself, ‘Something is wrong with our education system.’ I knew what happened to me wasn’t my fault. It was because my father was in the army, we kept moving houses, there was a war … These kids weren’t dealing with that but they were also failing. So I blamed the system.”

At the time, he was taking up his master’s at UST. Alarcon explored the flaws of the education system in a paper he was working on. “I wanted to find solutions to the problem.”

His quest led him to the cultural officers of different embassies. After talking with them, he discovered that some countries have educational systems that do not use grades. He wrote about all of this in his thesis.

In 1971, the Dominican Province of the Philippines was founded. Alarcon was elected its first provincial superior. Since the Dominicans had the Sto. Domingo Convent and the newly established parish church in Quezon City, there was a growing call for a school to be established as part of the Dominican’s ministry. “I said, if we will build a school, it will not be a traditional one.”

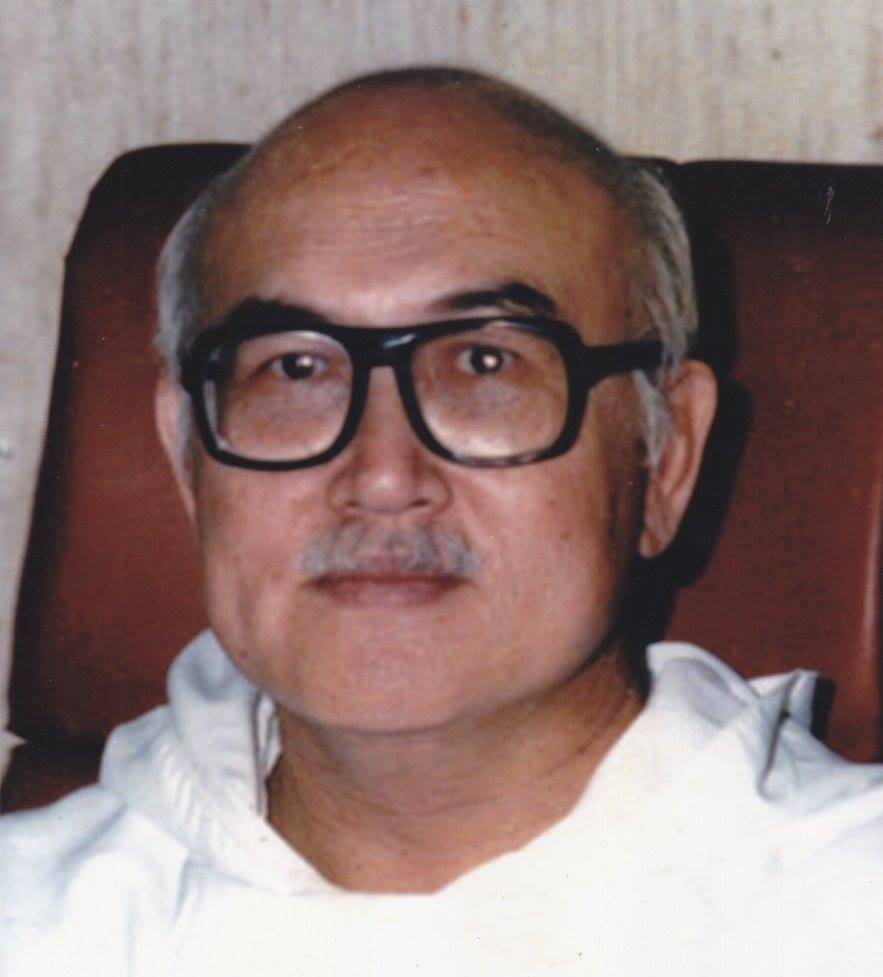

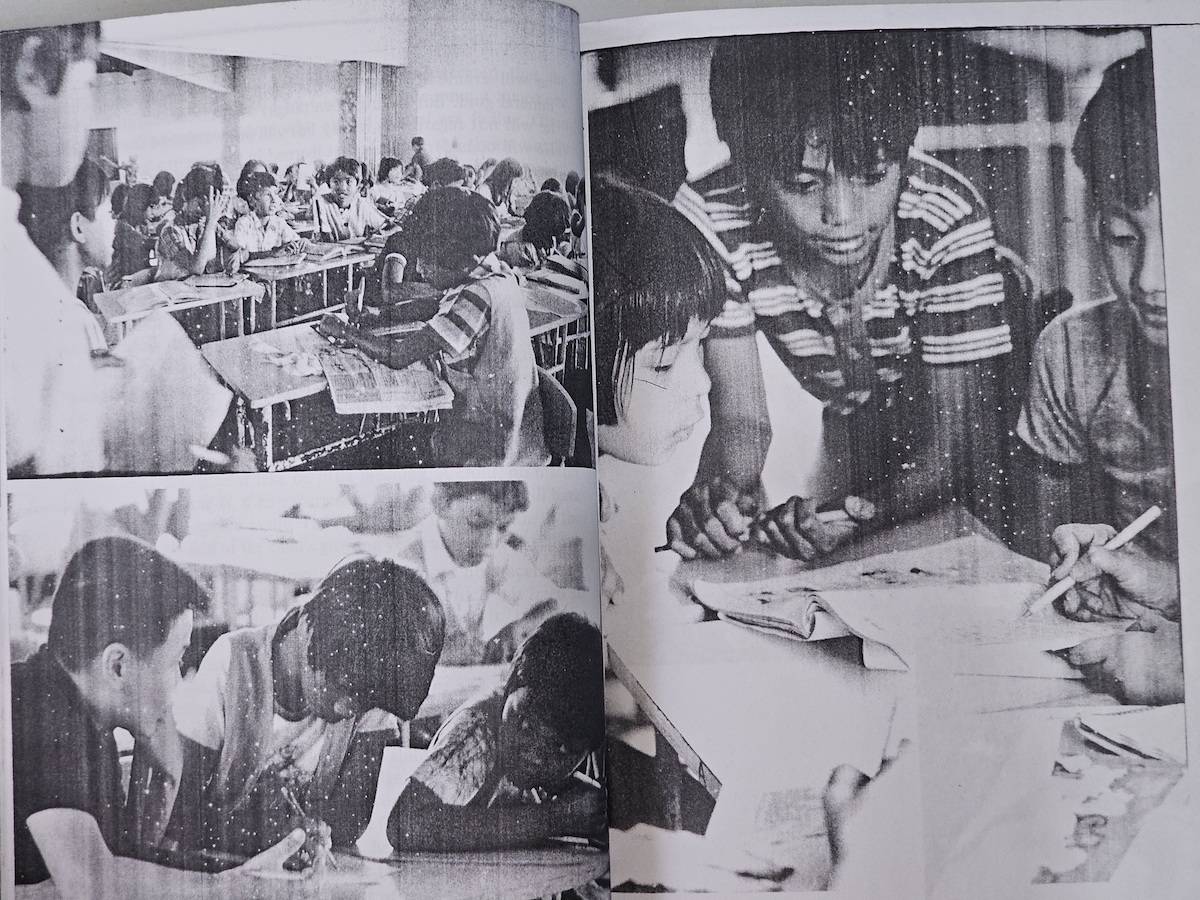

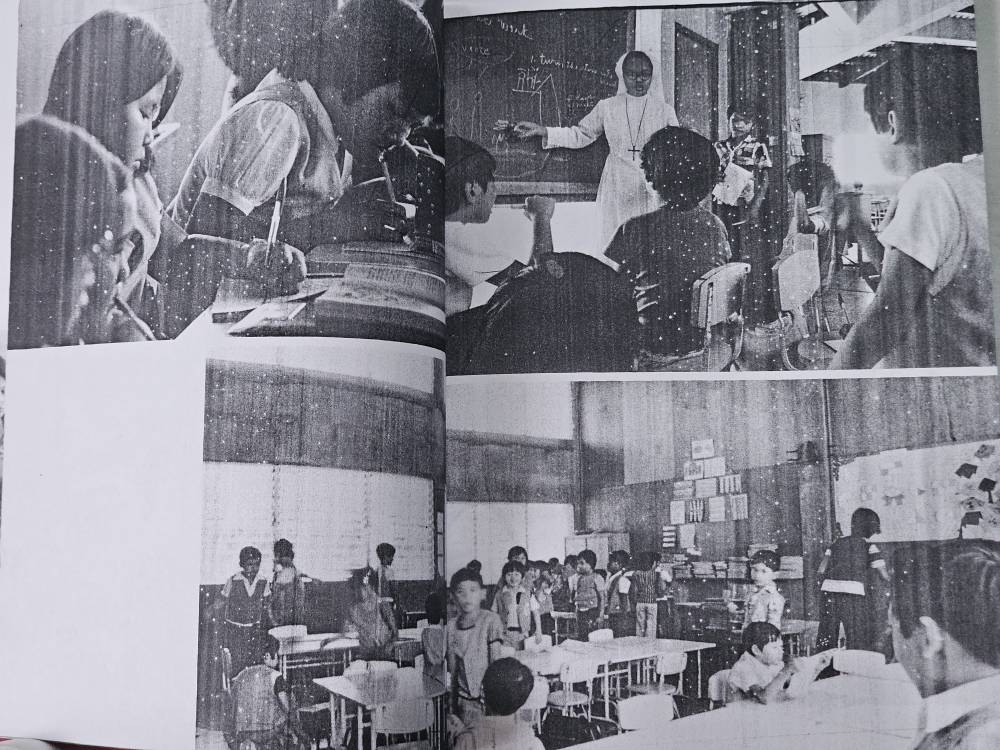

On July 5, 1972, Angelicum School was born. The school had six classrooms and a small library housed at the old Santo Domingo Seminary where nine teachers taught 315 young boys. This was the beginning of the self-paced, non-graded system Alarcon envisioned.

Instructions

When the school began operating, Alarcon gave instructions to guide the teachers. One, the school will not use a graded structure. While traditional schools had Grade 1, 2, 3 and so on, Angelicum used levels of learning.

Unlike the traditional grading system which was set within a span of time, with all students moving up after each school year, at Angelicum, when students master the required skills, they move on to the next level, regardless of the time of the year.

Two, there will be no marking system—no 75s, no As. Three, positive motivation was the rule. Scolding, ridiculing, embarrassment and punishment in any form would not be considered as disciplinary measures.

Four, Alarcon said, “It’s important for the teachers to know their students well because teaching will be done at the child’s individual pace and level. Teachers were free to do what they think is best for the child. The school relies mainly on the teacher’s sense of responsibility, although when inevitable, they will be free to approach the administrators.”

The teachers were given liberty to experiment, and the students were encouraged to use methods which best suited them. Alarcon believed that these changes were necessary to breed a fresh, new mindset for learning. The new setup also ensured that students were no longer held back, or pushed, by the requirements in their academic progress.

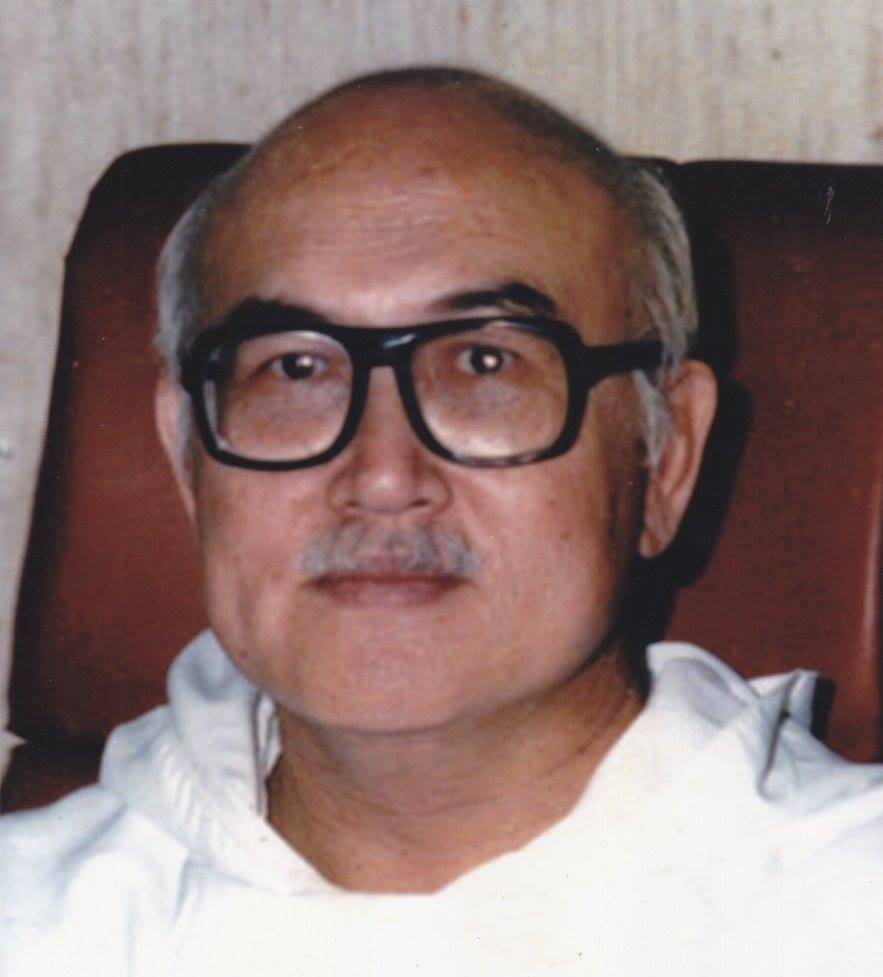

Alarcon, now 86 years old, believes that negativity stems from grades. He said, “In my experience, grades are the cause of cheating. Because of competition, students do not help each other. In a graded school, everyone wants to be ahead of the others.”

Competition is not part of the system he conceptualized. “Many times, the best students wouldn’t want to help their classmates because they want to stay at the top of the class. And that value is carried by the graduates. So, we see a world that is carried by competition. That is not what the Bible tells us. Jesus wants us to help one another.”

Academic excellence

He may not like the traditional grading system, but this doesn’t mean Alarcon isn’t dedicated to achieving academic excellence. He said that the education system should remove a mindset of mediocrity.

“We are encouraged by the Bible to do the best we can. It says, ‘Be perfect as your heavenly father is perfect.’ What is that? That is mastery. In the grading system, getting 75 means you passed, but that 75 means you did not get the 25 percent, you did not master it.”

Alarcon, a recipient of the Ten Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) award of 1972, believes that education is crucial to produce three types of love—love of God, love of country and love of neighbor. “The values are different. We emphasize love of God, love of country and love of neighbor very much.”

When asked if his system’s lack of competition becomes a problem to motivate students in learning, he said that the mindset of competition itself seems to be the problem.

He shared an anecdote that began at the beginning of one school year. He noticed a group of girls who were trying to avoid running into him. He asked them what was wrong and they told him, “Father, we lost in a basketball game.”

Alarcon asked the coaches to gather all the teams so he could meet with them. “I told them, ‘In a contest, there is always somebody who will get a higher score.’ When you play any sports, you should always be the winner. Number one, you are a winner if you play according to the rules. Number two, you are a winner if you give your best during the game. And third, you are the winner if you enjoy the game. With those three, you will always be the winner,” he said.

A week after that encounter, he ran into the same group of girls. This time, they waved at him and said, “Father, we lost.” Alarcon said, “Despite the score of the other team being higher, they were happy. Which means they are winners.”