Getting to know Capiz through its food and people

The province of Capiz has been earmarked as the seafood capital of the Philippines, with its 80-kilometer coastline and the long stretch of Panay River, both of which allow locals to harvest the freshest and most diverse produce from the surrounding water.

In my recent trip to this Western Visayan location, though, I discovered something that is just as prized and deserving of recognition as its terroir and title: the people. Over three days, we met some of the most generous Capiznons who not only let us into their workspaces, but also shared with us their success stories and recipes.

Pontevedra

Nanay Patring’s original recipe for dayok or Capiz’s version of bagoong, which was first formulated in 1955 by Patria A. Bulaqueña, created livelihood for her family, allowing her to send nine kids to school. Unfortunately, none of her kids wanted to continue her business. But her niece, Eva Bretaña, was more than willing and able to carry on her legacy.

Apart from the original recipe and the sweet and spicy variants, Bretaña innovated a product that makes her brand stand out. She recalled a vivid memory of the elders enjoying dayok with langkawas or galangal, a type of ginger, and so she came up with a product that fused both. The result is a condiment that has more character and flavor profile. Her humble business is thriving.

Panay

My idea of pusô is the one peddled on the streets and restaurants of Cebu, a dense pack of rice wrapped in coconut leaves, and typically dipped into a bubbling sauce of sautéed pig’s brain, or what the locals call tuslob buwa.

I was delightfully surprised to see a product of the same name, only reddish in hue and had a sticky gloss. As it turns out, the Capiznon pusô is eaten as a dessert. This was explained to me by Teresita Bering, who has been producing it for five years now.

First, she makes the balay, the casing made of coconut leaves, which comes in two designs—the male (pointed) and female (round). Then she half-fills them with rice, ties them together to make a pair, then drops them in a vat of tuba vinegar, which her husband gathers early in the day. The pouches are then cooked for five long hours until the liquid becomes lasaw, akin to molasses. They are taken out of the pool, rested, and sold for P15 a piece.

Roxas

Nick Dolendo was born in Antique but has lived for 15 years in Capiz to build his own family. Straight from the airport, we met him at The Edge, a restaurant perched on top of a hill that required a five-minute trek.

There, he prepared a home-cooked breakfast spread of local dishes that clearly showed the province’s seafood and vegetable bounty, something he confessed to appreciate now that he’s living in this part of Visayas. “This place is a great source of fresh produce. We have many options and mas mura pa dito,” he said.

While admiring the panoramic sea view inside a nipa hut, we gorged on fish tinola with lemongrass and alukon, adobong takway, pinakbet, sinaing na matambaka sa kamias, banana chips with tuyo salsa, and pandan biko with bukayo.

My good friend, Cristina Syching, who is the president of Hercor College in Roxas City, welcomed us at the Palina Green-belt Eco Park where guests can ride and have lunch aboard the floating cabanas while on the clean water of the Palina River.

Our lunch was a feast of discovery as I got introduced to lesser-known regional dishes: puyoy or small eels prepared two ways—grilled and fried; tahong na sisig; ginataang gabi with bagungun; pinamalhan or fish slowly cooked in vinegar, salt, and ginger until it becomes a bit dry; binakol sa dahon or pork and beef cubes, cow’s brains, and kamias wrapped in banana leaves then steamed; fresh stalks of fern called palaypay that had been boiled, pounded, and cooked in coconut milk; and papisik, lemongrass-stuffed chicken cooked in a clay pot filled with salt.

While sailing through a lush mangrove, I got to sit down and chat with Jose Roy Depon, a former seaman, who, with his wife, invested on a plot of land and grew cacao trees, not knowing there was a potential business there. He attended trainings and tried his luck in making products, including a tablea seasoned with dried fish. It won third place at the Cacao Congress.

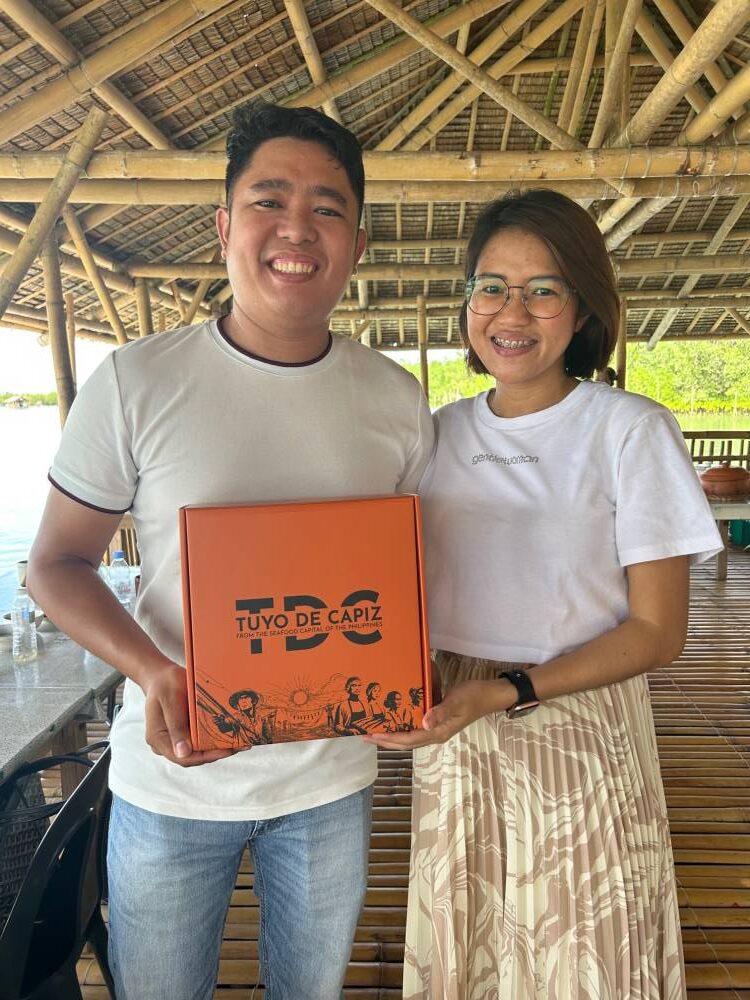

I was also introduced to couple JR and Lucille Dalida, third generation of a family of mag-tutuyo. Both were working in Singapore when the pandemic hit. Sadly, they lost their jobs and were forced to come home.

It wasn’t exactly an unfortunate twist of fate as it allowed them to take over the family business and incorporate their innovation and industry know-how. The result is Tuyo de Capiz, beautifully and properly packaged dried fish that comes vacuum-sealed and boxed. They now export to countries like Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States.

Ivisan

After visiting the water pens and learning how the people sustainably gather fish, we proceeded to nearby Patio Beach where we were treated to a lunch prepared and cooked on site by a team of ladies from a local community, namely Dyna Bonitez, Sandra Vargas, Josephine Olisco, Magie Oberas, and Villa Villar.

The spread consisted of dishes they would normally eat at home with their own families. We indulged on ginataang tambo na may kasag at mais, a fish paksiw where kamias took the place of the vinegar, sweet and sour dilis, adobong pusit, and tinolang isda with labog.

Cuartero

Before heading back to Manila, we took a detour to the Capiz Ecology Park and Cultural Village to soak up more of the province’s food culture. They set up stations where cooks demonstrated how to do some of the local fare, including the binakol na manok sa bamboo, ginataan na pantat na may balinghoy, nilupak, bitso-bitso, inday-inday, and even puto sa tuba.

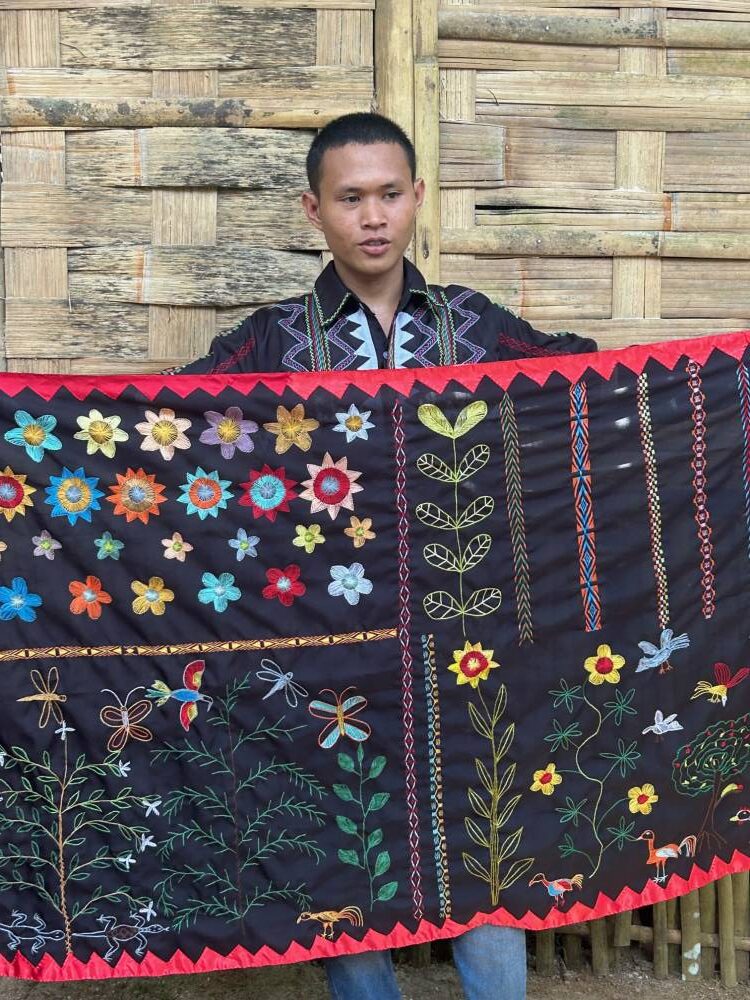

The highlight of this day was when the Panay Bukidnon tribe gave us a peek into their culture by sharing the stories behind the colorful patterns of their panubo outfits, delighting us with a traditional courtship dance called binanog, and showing us how to cook inubudang manok and a burnt rice drink called sara-sara.

This Capiz trip was quite a revelation as I learned so many things in such a short span of time. It was quite immersive and impressive, one that will definitely go down as a favorite in my travel book.

Special thanks to Al Dalisay Tesoro of the Capiz Provincial Tourism, Harold Ortiz Buenvenida and Ramon “Chin-Chin” Uy Jr., president of Slow Food Negros.

Angelo Comsti writes the Inquirer Lifestyle column Tall Order. He was editor of F&B Report magazine.