He carves out grief and memories with rubber cuts

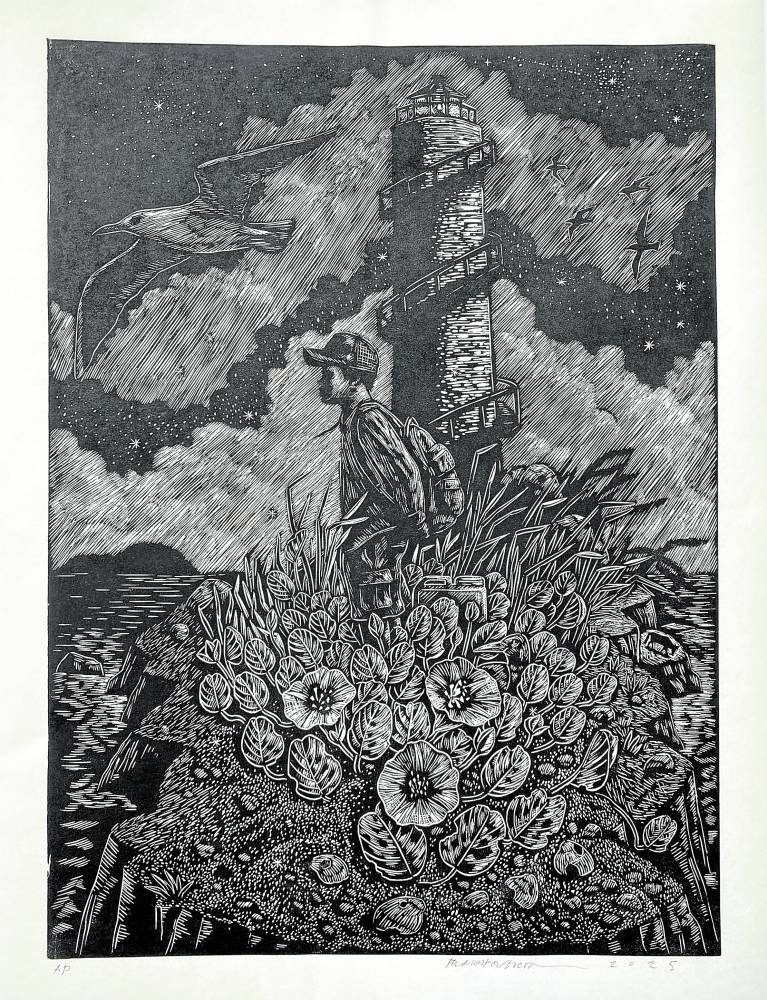

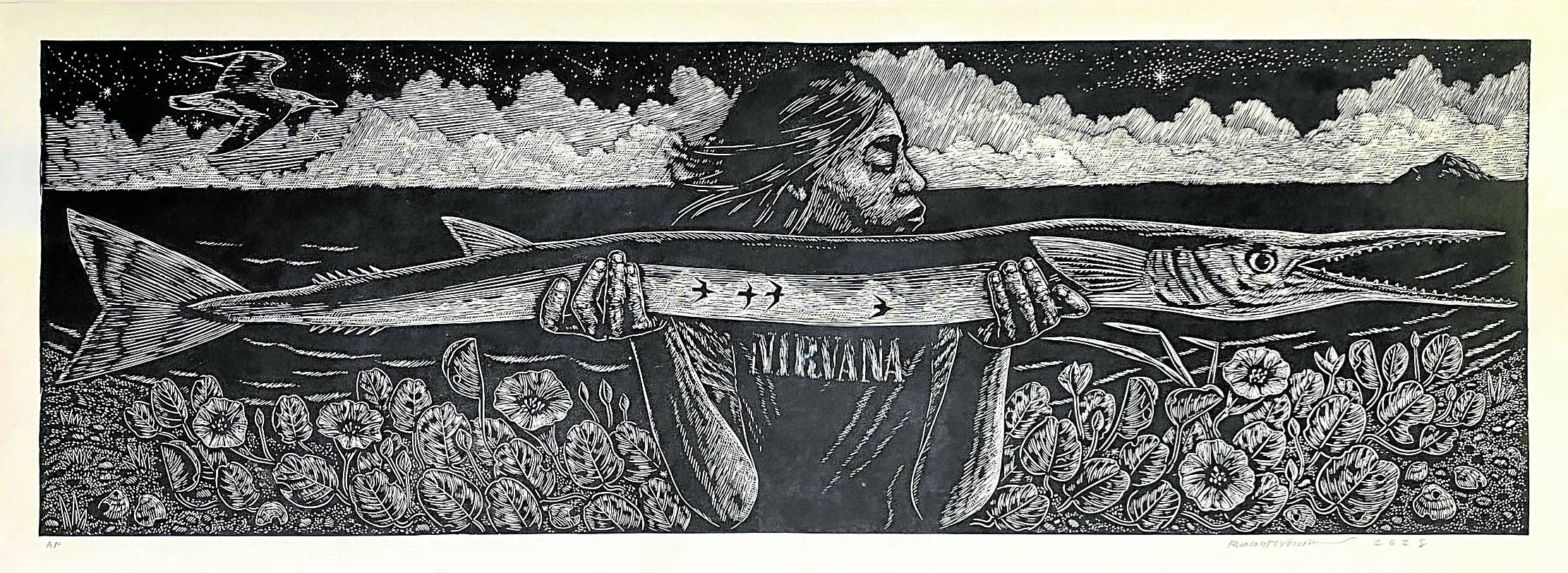

Printmaker Filomeno “FM” Monteverde Jr. grew up in a house not too far from the shore of the sea in Taggat, Claveria, in Cagayan province where tales of mermaids were common. He remembers the windows where he would “watch the waves rage during the onset of a typhoon. On calm summer nights, the rhythmic slapping of waves against the shore lulled me to sleep.”

When he later moved to Aparri, 130 kilometers away, to live with his aunts while his mother was ill, the sea was still present, only four blocks from the house, but he heard stories of mermaids abducting children, even adults, so that kept him from venturing too close to the waters.

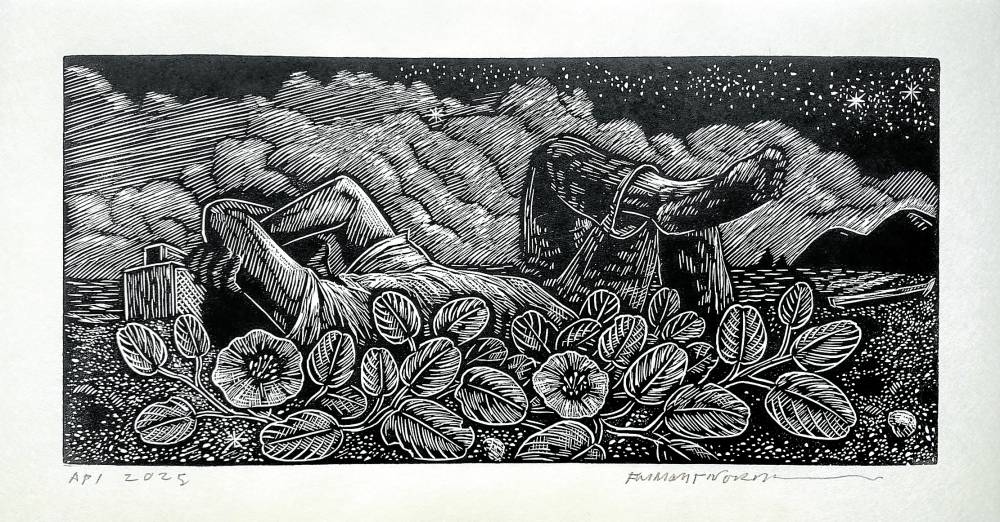

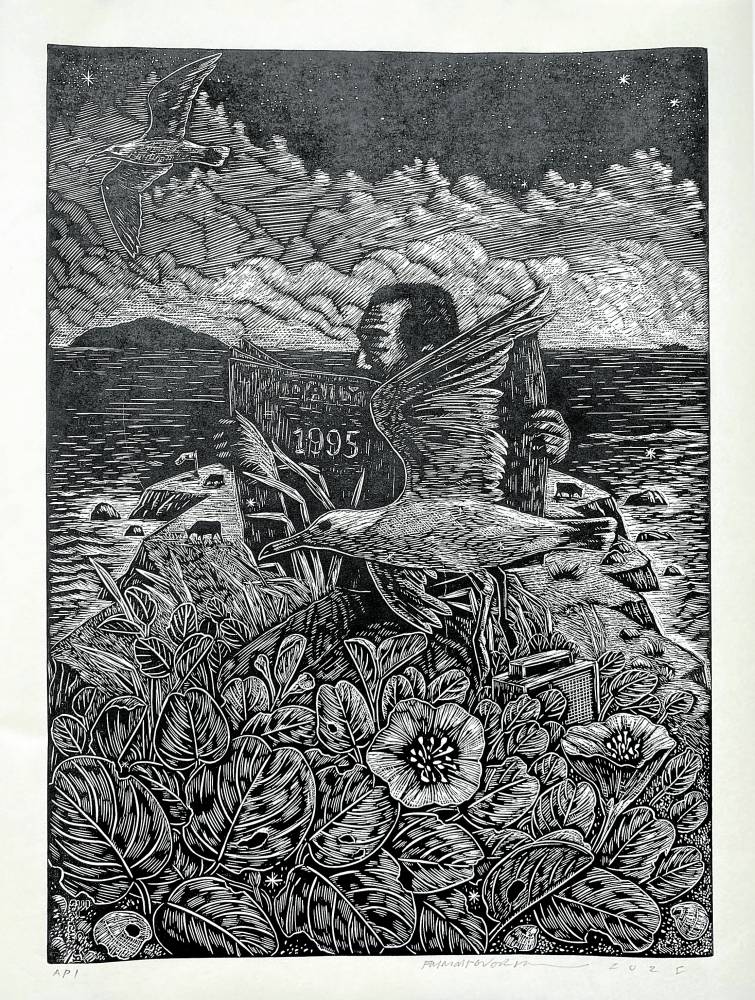

Last year, as he prepared for his exhibit, “1995: Murmurs of the Sea,” ongoing until March 23 at Pinto Art Museum’s Upper Gallery 4, he returned to those towns, he said, “to rekindle old memories and immerse myself once more in their landscapes, scents, and stories.” This time, he discovered the correspondence between his father, who was stationed on Mabag Isle, next to Fuga Island and part of the Babuyan Islands, and his colleague in Claveria.

The older Monteverde was an engineer working as plant superintendent at a timber processing company. After the Edsa revolt in 1986, the government sequestered the company. More than a decade later, it lost its logging concessions and was on the verge of shutting down. As part of his job, the older Monteverde was sent to the island for maintenance work.

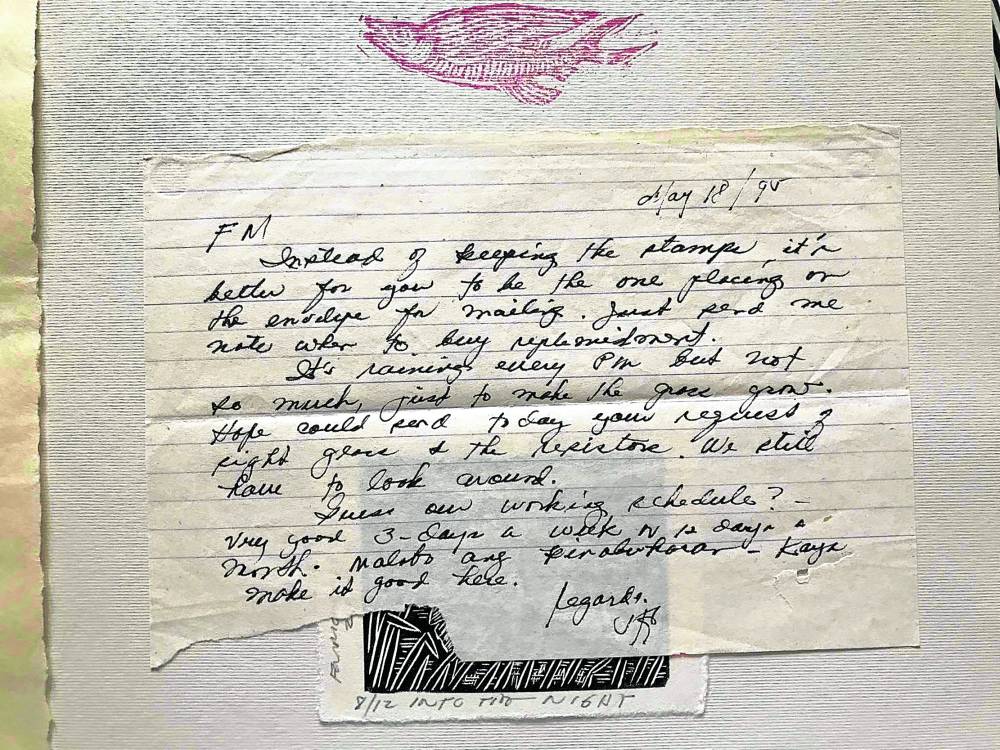

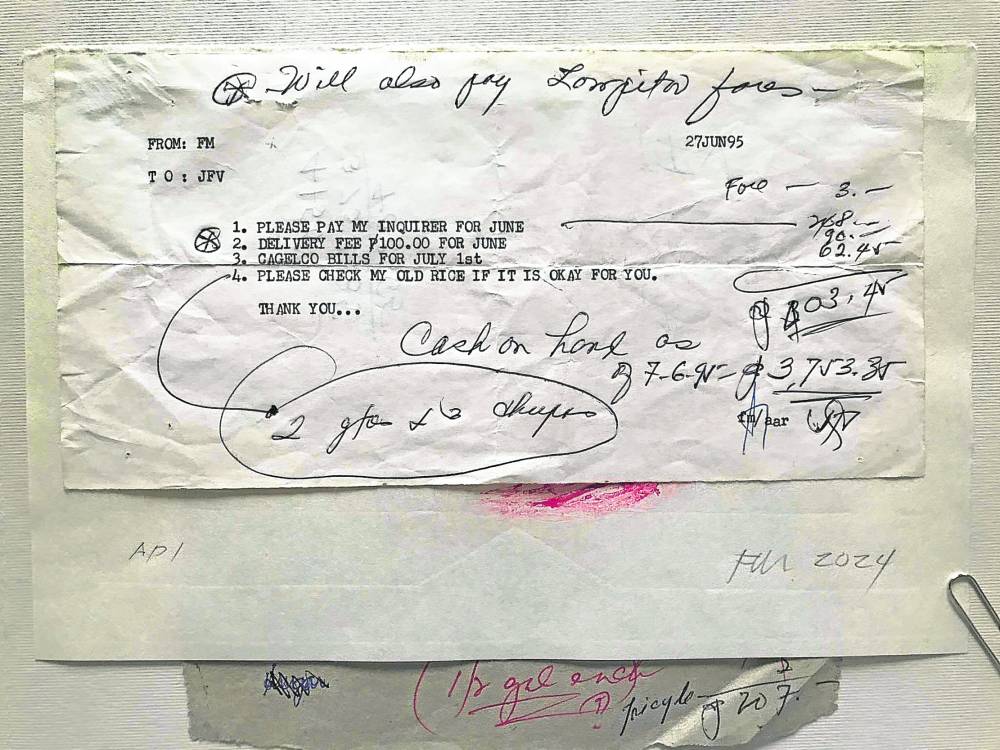

Unsent letters

The messages, transmitted via radio, contained requests for resupply, along with more personal matters: checking on the house, paying the electric bills, and sending newspapers via the lampitao (a small boat with an engine). Among these telegrams were unsent letters addressed to FM Jr., dated 1995.

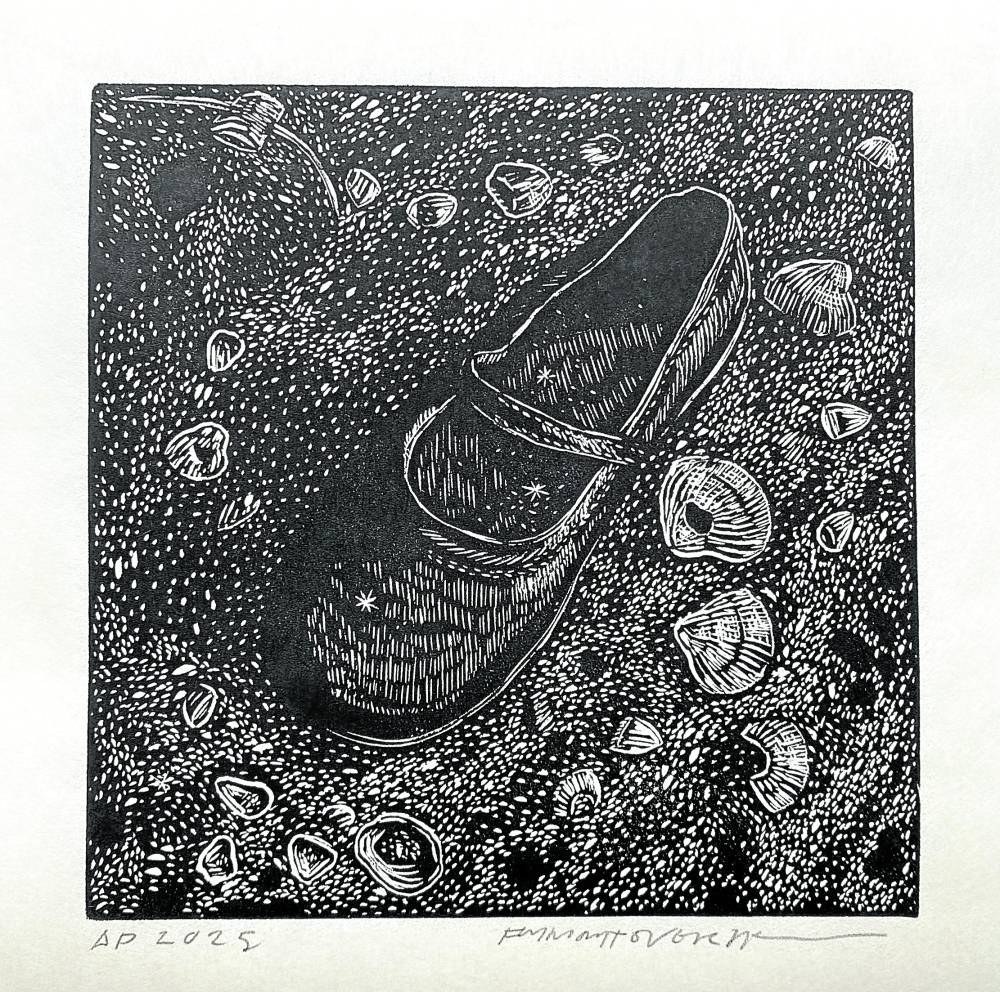

What follows, curator Carlomar Arcangel Daoana writes in his notes, is Monteverde’s “meditation on loss—both personal and universal. The personal: loved ones who have departed, objects once treasured but now irretrievable. The universal: the slow vanishing of untouched landscapes, the erosion of innocence before modernity, the quiet unraveling of nature’s beauty when it exists not as a resource but as an unfettered wonder. Loss, in its many forms, is at the heart of this body of work, but so too is the act of searching, even when what is sought is irretrievable or remains undefined.”

With rubber-cut as his medium, the artist, after graduating from the University of the Philippines-Baguio with a degree in fine arts, set himself “adrift to find inspiration” for decades. He would sometimes paint, but as the years dragged on, he saw himself becoming more of a spectator than an artist.

But he encountered teacher-printmaker Darnay Demetillo in Baguio. Monteverde says, “It was Darnay who introduced me to printmaking in the early ’90s. At the time, he was preparing for an exhibit and demonstrated how to carve linoleum. But this wasn’t the soft linoleum we have today—it was the kind used for flooring. Back then, sourcing printmaking materials was difficult. Darnay would buy tingi-tingi (small portions) of ink from printing shops for our printmaking class. Around the same time, in Baguio, I saw BenCab’s intricate etchings of miners on display and was completely blown away.”

When Monteverde moved to UP Diliman, Neil Doloricon became his figure drawing instructor. He recalls, “One day, as I was submitting a plate, I noticed him working on a rubber-cut print. He generously shared insights into his process, further deepening my appreciation for printmaking.”

Meditative

Lately, Monteverde has been “carving blocks outside in a space fit for a small table, two chairs, and a black cat to roam around. Preferring natural light over the lamp, my renewed interest in block printing began after the great sorrow after my father’s death. Many things were going on inside my head then, and I was looking for a way out of the grief. Working on the block became a meditative process. When the mind is at peace, the story it tells is clear and crisp.”

He chose printmaking over the other visual arts because carving the block, applying the ink, and hand-burnishing the paper are “both demanding and meditative. Each step requires patience and precision, but once you find your rhythm, the repetitive motions create a deep sense of focus and connection to the work.”

He adds that “no two prints are exactly identical. Each edition carries its own subtle variations, making every piece unique. Printmaking’s power lies in its ability to create multiples while staying true to the original. This makes the work more accessible. The more people it reaches, the greater its impact.”

Pinto Art Museum is at Grand Heights Subdivision, 1 Sierra Madre St., Antipolo City.