How a poet found PH in colonial art

It was a modernist museum, and an art exhibit by Fernando Zobel in the 1960s, that led Renato “Butch” Santos to inquire about the genesis of Philippine art and eventually start collecting traditional art in the form of religious imagery.

He was a student then of the Ateneo de Manila University and the country’s first modernist museum, the Ateneo Art Gallery, had just opened.

Now in his 80s, the retired banker and Palanca award-winning poet has launched a book on his interpretation, his views on what really is colonial art through his reading, observations, and experiences as a collector and life-long student of art history.

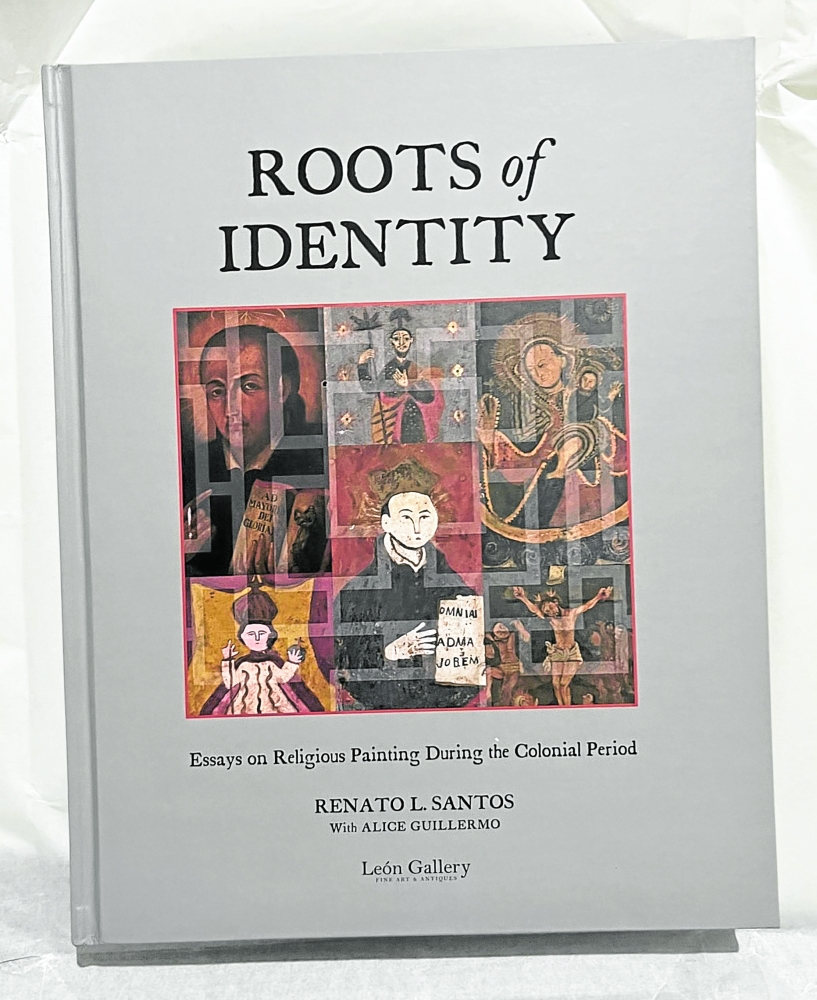

At the launch of “Roots of Identity: Essays on Religious Painting during the Colonial Period,” published by Leon Gallery, attendees included some of the country’s art and culture luminaries such as Esperanza Gatbonton, Jaime Laya, National Museum director-general Jeremy Barns, and Gemma Cruz-Araneta.

On display were artworks from Santos’ collection, including those from the Lucban school of Vicente Villaseñor, those attributed to Simon Flores, Bohol religious art, and exquisitely framed religious and nationalistic tableaux.

Santos’ love for religious art may have unconsciously started in his hometown of Concepcion, Malabon, a village known for its devotion to the Nuestra Señora de la Concepcion.

One of his first pieces is the image of the Our Lady of the Rosary, a possible work of Simon Flores which graced the cover of the culture and arts magazine Archipelago, and part of the week-long exhibit.

The book was initially planned in the 1970s but did not push through for “lack of specimens to dissect.”

In his speech at the launch, Santos said that the value of collecting art is not in the millions it will fetch, but in the sense of cultural identity gained. These pieces, he said, are “touchstones to the evolving value of Filipino identity.”

Influences

In the book, Santos starts with the introduction of religious images as a contrivance for attracting faith, and discusses the idea of “visual anthropomorphism” by the Spaniards to propagate Catholicism.

He likewise touches on the devotion to the Virgin by the various religious orders; the lesser-known Jesuit painters, the Italian Francisco Simon and Manuel Rodriguez, whose works are undetermined to this day; and eclectic influences in art such as the Chinese character of Esteban Villanueva’s 1821 “Basi Revolt” paintings.

Santos also delves into the rise of the ilustrado in the 19th century, which introduced a style called miniaturismo, and provides his insights on the folksy traditions of Bohol and Siquijor, the lagang (shell ornaments) of Cebu, nationalism in art, and the social conditions that created these works.

In an essay written in the 1970s, the late art critic Alice Guillermo investigated the factors that produced regional iconographies and syncretism in art.

Through Santos’ analysis of artworks and in-depth observation, he stitches together the history of colonial art in the country and provides an intimate take on its development anchored on an educated examination of its many aspects.

In one of the essays, Santos writes that “it will be simplistic to label culture as an admixture implying essential innate awareness of the sacred, homo religious defiled, or a state of original purity forgone.

“Culture, after all, is life, and life is never a done deal; rather, it is lived with liminality, always in transition, in gall and grit contextualized,” he adds.

It is in this context that the book is recommended to be read, for one to have a grasp of what is Philippine art and the Filipino identity through centuries of art and art-making.