Icon and ‘papabile’: Tagle, St. Caesarius, and the Holy Spirit’s descent on Manila

In the hushed baptistery of the Manila Cathedral, where generations of Filipinos have received the sacrament of rebirth, a new icon rests—silent, striking, and almost otherworldly.

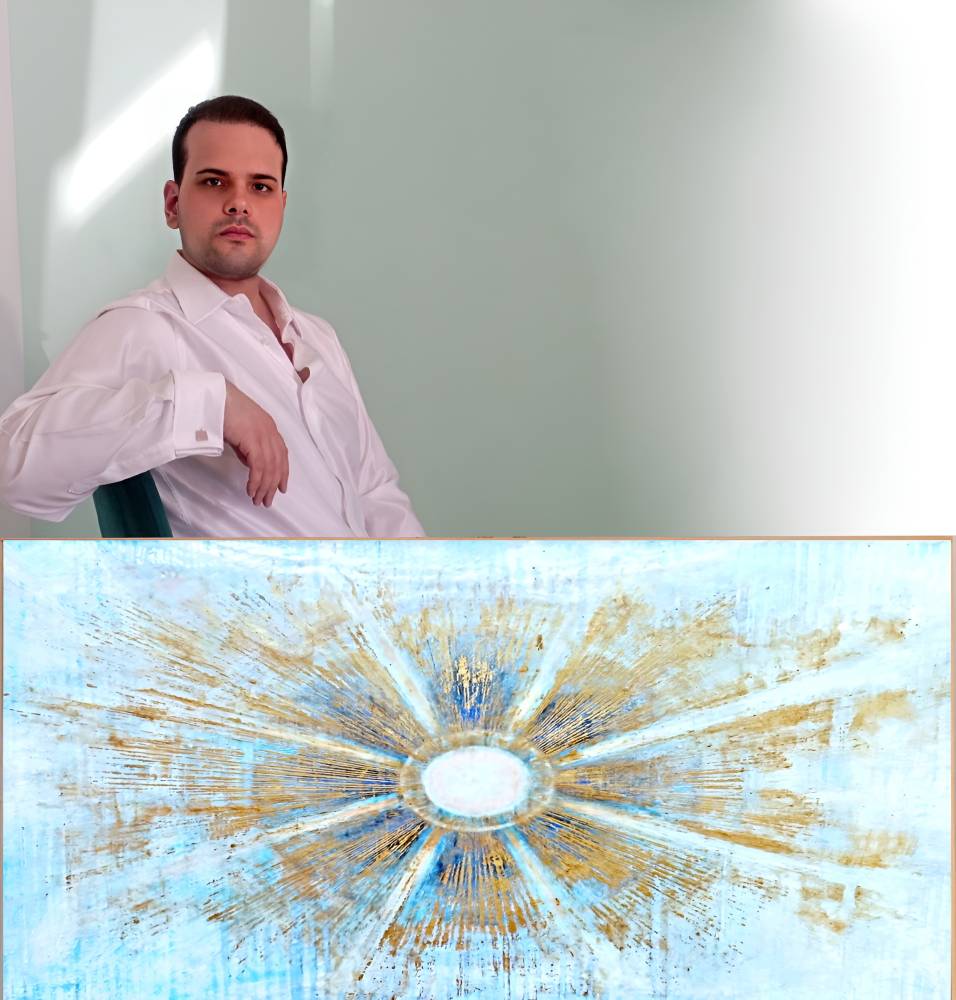

“Caesarius Diaconus,” a painting by Italian artist Giovanni Guida, portrays a young martyr-saint without a halo, stripped of grandeur, gazing not upward but outward—toward us.

More than just a painting, the work—gifted in 2015 to Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle when he was Archbishop of Manila—is a spiritual act, a Pentecostal gesture, a breath of divine imagination.

“I reflected deeply on the final words the young deacon might have spoken to the Roman judge before being sentenced to death,” Guida told this writer in a recent interview. He was referring to Saint Caesarius of Terracina, martyred in 303 AD by being sewn into a sack and cast into the sea.

Guida imagined the saint saying, “The water in which I was born anew will receive me as its son.” That imagined farewell inspired him to offer the work to the Filipino people. “They don’t explain faith,” Guida said. “They live it.”

In the Philippines, baptismal water is not merely symbolic—it is a lived reality. Guida draws a parallel between this and Pentecost, where the descent of the Holy Spirit becomes an act of rebirth—a divine breath that animates both body and image.

Guida’s “Caesarius Diaconus,” then, is no mere icon. It is a portal, a work that bears the memory of a Roman martyr while revealing the artist’s incarnate theology of art. For Guida, the sacred is not applied to the surface—it is uncovered beneath it.

Born in 1992 in Acerra, near Naples, Giovanni Guida is part of a rising generation of contemporary European artists. Trained at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples under Mariarosaria Castellano, Guida developed his signature style through grattage, a technique pioneered by the surrealist Max Ernst. It involves scraping away layers of pigment to reveal hidden textures beneath.

But for Guida, grattage is not just a method—it’s theology.

“Just as grattage tears away pigment,” he said, “Filipino history has endured colonization, war, and poverty—yet from beneath those scars, light emerges. The tear becomes revelation.”

The temple veil

Every scratch, every stroke of the blade becomes a metaphor for the spiritual rupture that allows grace to enter. Guida often evokes the biblical image of the temple veil being torn in two—the moment when the sacred is revealed to all.

“The veil falls forever,” he explained. “It lets you see what is hiding.”

The result in “Caesarius Diaconus” is a striking composition. Painted in vibrant blues reminiscent of lapis lazuli—the sacred pigment of Byzantine icons and Michelangelo’s ceiling—the painting feels at once ancient and contemporary, fractured and whole. Unlike conventional portrayals, Guida’s Caesarius appears unadorned and vulnerable. He is “a beardless youth,” the artist said, “without a halo, placing himself at the service of others, offering himself wholly and unconditionally.”

During the Jubilee of Mercy in 2015, Guida offered a series of Caesarius icons to churches around the world. One was given to Cardinal Tagle, then archbishop of Manila and a rising figure in the global Catholic Church. (Pope Francis would appoint him pro-prefect of the Dicastery for Evangelization in 2019, and Tagle later became a papabile—or papal contender—at the most recent conclave.)

But Guida’s gesture was not political; it was pastoral.

“In him I saw the transparency of the simple,” Guida said. “The silent voice of peoples awaiting a shepherd with a human face.”

That offering was made with a quiet hope. “I held in my heart the hope that the Ruah—the Spirit—would descend upon him,” Guida recalled.

Today, that spiritual thread continues. Guida’s latest painting, again offered through Tagle’s hand, affirms their shared vision: to bridge art, faith, and people. “One through the faith that animates communities,” Guida said of Tagle, “the other through the beauty that uplifts the spirit.”

Guida’s admiration for the Filipino faithful runs deep. In the interview, he referenced Cratylus, the Greek philosopher who, disillusioned with language, chose to communicate solely through gesture.

“When I think of the Filipino people,” he said, “I see the personification of Cratylus. They do not explain faith—they live it.”

This embodiment of belief—this sacramentality woven into everyday life—is what Guida seeks to honor. In the Philippines, he observes, religion is not confined to Sunday rituals. It is breathed, sung, worn. “Their silence is not absence,” he added. “It is fullness.”

That incarnate spirituality has entered the classroom as well. Guida’s grattage technique is now taught to Filipino students as a kind of visual catechesis. “To teach the young to scratch beneath the surface,” he explained, “is to teach them to see the sacred in the hidden.”

Pentecost for the poor in spirit

In a country where religious imagery saturates the landscape—from jeepney Madonnas to mass-produced crucifixes—Guida offered a word of caution: “The sacred risks becoming invisible through excessive familiarity.”

His art, by contrast, seeks not to repeat but to awaken. It invites not doctrinal clarity, but sacred encounter. “True sacred art does not explain the divine—it points to it,” he declared.

This Pentecost Sunday, when the Spirit descends like fire and wind, Guida’s Caesarius offers a similar gesture. It draws the faithful not into explanation, but into breath. Into vulnerability. Into silence.

As the painting now rests in the Manila Cathedral’s baptistery—where water and Spirit continue to meet—it speaks without words. It offers no answers, only presence. Only the possibility that beneath the scraped surface of our lives, the sacred still waits to be revealed.

The Manila Cathedral is not the only place touched by Guida’s vision. Portraits of Saint Caesarius now hang in churches across Europe and Asia, part of the artist’s mission to rekindle devotion to the little-known Roman deacon. In Rome, the spiritual lineage is closer to home: Guida’s uncle, Dom Marius Bove, serves as rector of the Church of San Cesario de Appia, continuing the saint’s legacy within the Eternal City.

What emerges from all this is the image of an artist quietly reshaping sacred art for a contemporary world—not by rejecting the past, but by piercing through it.

Guida’s work does not catechize in the conventional sense. It does not command belief. It invites it. By opening “spaces of silence within the noise of the already seen,” his icons restore mystery to the overly familiar. They remind us that the sacred is not lost. It is only buried—waiting to be scratched into revelation.

And in the Philippines, a land where faith is worn into the rhythm of daily life, that revelation finds its truest echo. Caesarius Diaconus may be Roman by name, but in the gentle hush of the Manila Cathedral, the saint’s silence speaks in a Filipino tongue.