In the tropics, nothing is permanent

In his latest exhibition “Seiches” at Artinformal Gallery, artist Kristoffer “Kris” Ardeña returns to one of his foundational concerns: what a painting can be when rooted in the Philippine tropics rather than in Western art history. Based in Bacolod after living around the world, the artist is firmly committed to the landscape, climate, and material realities of the Philippines, shaping a practice that is as philosophical as it is physical.

Ardeña was born in Dumaguete, where he eventually moved to Germany and Luxembourg as a teenager, then went to University in the US. Later, he moved to Spain, and then moved back to Bacolod, where he currently anchors his studio practice.

Despite his long ties to Europe, Ardeña states that the light and life of the continent didn’t really affect his work. But when asked about the Philippines’ influence on his practice, it’s a different story. “[The influence is] 100 percent, I would say. I would say it’s deeply rooted in that aspect,” he says.

The exhibition’s title, “Seiches,” comes from a scientific term describing a standing wave that forms in an enclosed or partially enclosed body of water—like the rhythmic sloshing in a lake, a bay, or even a bathtub after a disturbance. A seiche is subtle but powerful, a movement that’s almost invisible from afar yet continuously reshaping the surface.

The use of the word seems to show in images that convey these ripples in histories and everyday realities—almost imperceptible, but persistent in Filipino life and, by extension, Ardeña’s work.

Just as seiches reveal themselves only when one looks closely, Ardeña’s paintings, with their embodied realism, crack surfaces, and layered substrates, pull viewers to pay attention to what shifts beneath.

Elastomeric paint as a tropical language

Perhaps Ardeña’s most distinctive material choice is elastomeric paint, which comes directly from the Philippine-built environment. “Elastomeric paint is the kind of paint that we use in the rural areas… and for me, it’s important because I was also looking for a paint medium that had the same formal characteristics as oil or acrylic,” he explains.

The artist wanted a medium that could function like traditional Western paint, yet belong to a Filipino everyday experience. “If people don’t ask, people wouldn’t know. They probably would think it’s acrylic, and some might even think it’s oil.”

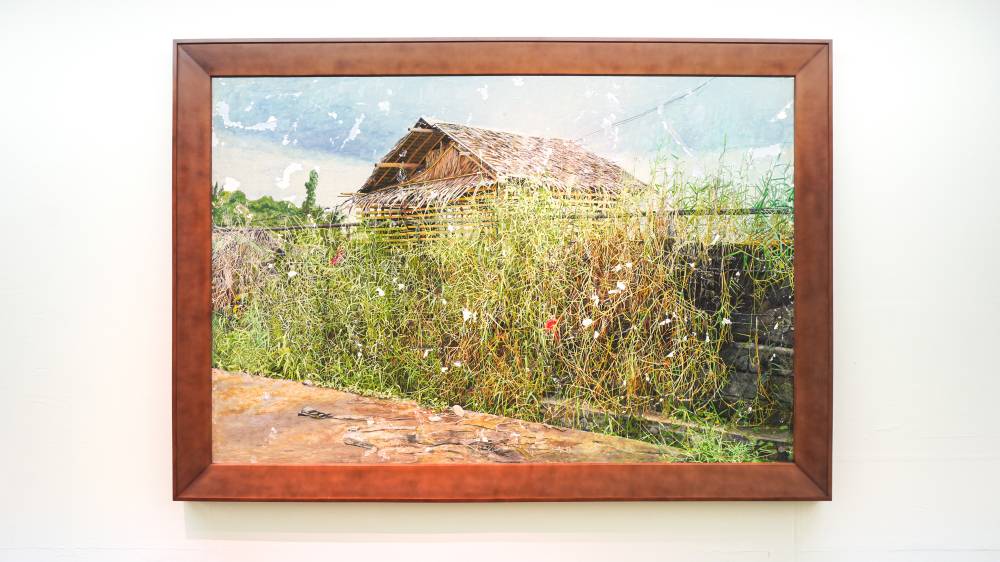

His shift from using borrowed, Western standard materials to local, ubiquitous, tropical ones is a conceptual turning point. It is also deeply technical. Ardeña’s signature cracked surfaces took two years of research. “The cracking itself for me is important because I wanted to have a technical trope that alludes to the tropics… cracking is something that naturally happens, and we see it a lot in buildings in the Philippines,” he explains.

For Ardeña, the cracks are not flaws, but evidence of climate with its unflinching humidity, lived history, and impermanence, as well as a sense of politics, all forces that shape the structures of the Philippines.

“The west wants the work to be eternal… conservation… because there’s also a monetary value attached to the work.”

But what is permanence in a country of typhoons, humidity, decay, and constant repair? He cites the example of jeepney seats, where paint is often trapped under the plastic, and the upholstery becomes worn and torn, an aesthetic very much obvious on the surfaces of his paintings.

“Our relationship to permanence and impermanence is very different. And I wanted to imbibe that in the paintings… to contest that idea of permanence in the West,” he says.

Ardeña questions why the structure of painting, its materials, processes, and image-making assumptions, remain tied to Western models even as Filipino artists insert Filipino narratives. “Painting in itself is an inheritance from the West. It’s a colonial inheritance,” the artist notes. “And for me it’s important that we also question and be critical about the medium, but rooted in our everyday experience in the Philippines.”

Realism embodied

As Ardeña continues to reject Western assumptions of painting, he still takes on the long tradition of realism. “A lot of realism in the classical sense is descriptive… So what I do… the realism is not described. It’s embodied.”

He paints the cracked surfaces of elastomeric paintings in portraits of regular, everyday Filipinos, from Masskara dancers to public school teachers, janitors, and a flag seller, as well as renditions of “Balay Tropikal.”

Ardeña also presents a variety of his practice. In one of what he calls his “Ghost Paintings,” he specifies it as a “Study after a Tricycle Sidecar and a Sari-sari Store, ” with GI metal tubular frames and sachets of Filipino products from Nagaraya to Pantene. On another “Ghost Painting” with tinges of purple, pink, and teal, he features shells from Sipalay beach divided by corrugated clear polycarbonate roofing.

Rather than paint representations of objects, he also puts latex paint onto the objects themselves, such as mannequins, a coconut, and a coffee cup.

Or he paints directly on tarpaulins from election seasons, making the printed and painted surfaces nearly indistinguishable. If the artists hadn’t revealed the tarp’s origins, viewers might simply see an orchid. This is also how he addresses the political “in a more poetic way… without it being didactic or moralistic.”

“Sometimes you get confused which is the painting and which is the printed image… because the realism is embodied in the work, it’s not described,” Ardeña says.

In the tropics, nothing stays untouched. Ardeña is conscious and assertive of this truth.

A reframing of painting from the ground up

Ardeña seems to be a pretty chill guy, with an unassuming demeanor. But after a few minutes of chatting, it’s clear he is relentlessly analytical, with work that reveals a constantly probing mind rethinking the structures of art. Still, he does not dictate the narrative of his paintings. “Anything when it enters a perceptual field of the viewer will always contain a narrative… the narrative is created and completed by you, the viewer.”

He shows radical generosity in a landscape where political messaging in art is often didactic. The artist uses these objects, materials, cracks, and fragments, not as conclusions, but as clues. So what Ardeña ultimately attempts is not a change in subject matter, but in structure, the foundation upon which painting often operates.

“It’s important to start with the parameters of painting because we also need to innovate and reframe how we think of painting, but from the Filipino perspective… Because imagine in 50 years… the structure doesn’t change.”

With “Seiches,” Ardeña seems to offer a proposition: Painting can be tropical. Painting can decay. Painting can crack. Painting can carry politics without explaining them. Painting can be Filipino, not by narrative, but by structure, very much alive, changing with the climate and the times.

“Seiches” by Kristoffer Ardeña runs from Nov. 27, 2025, to Jan. 7, 2026, at Artinformal Gallery, The Alley at Karrivin, Chino Roces Ext., Makati