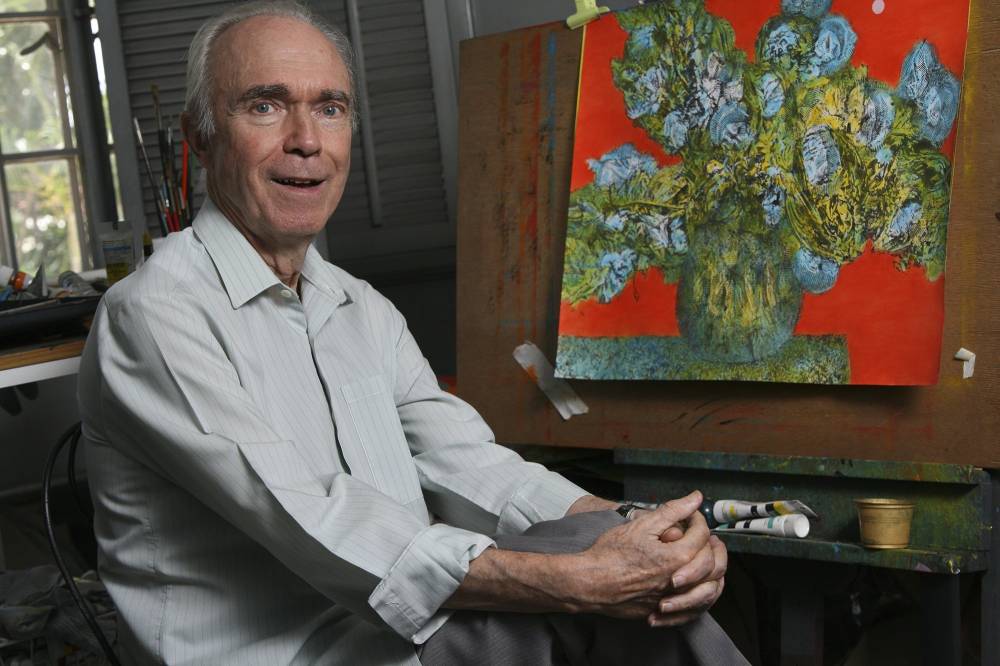

Juvenal Sansó: ‘My paintings are like my fingerprints’

This interview was conducted in the artist’s San Lorenzo Village, Makati residence, in March 1973.

Cid Reyes: Do you always base a painting on a preliminary design or study?

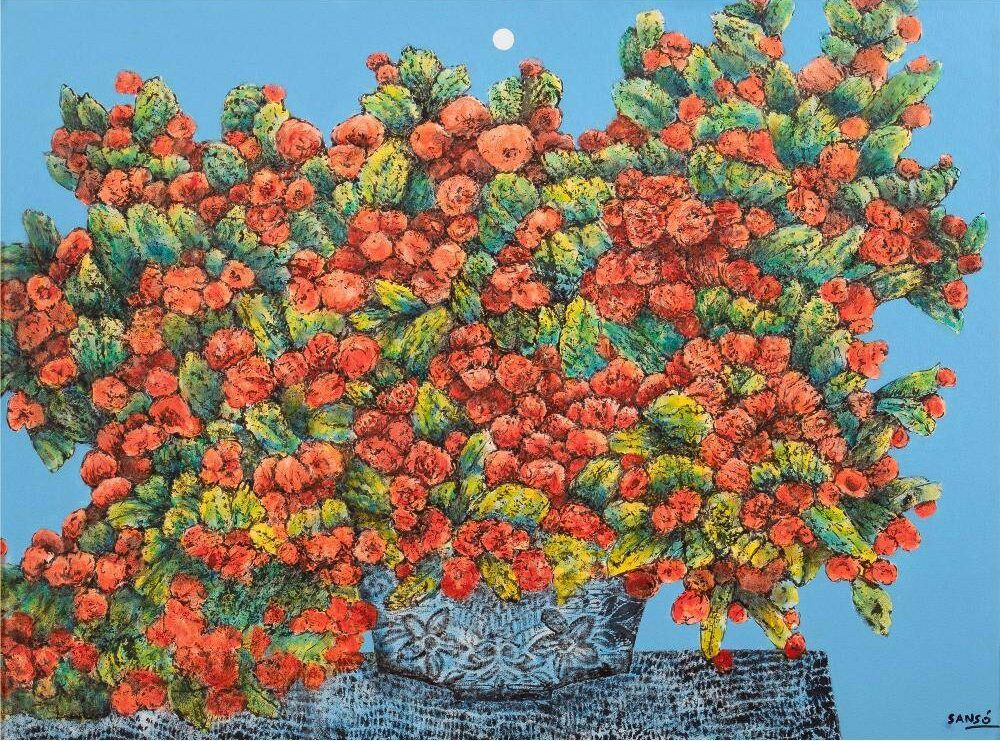

Juvenal Sansó: No, never. I do endless studies, as you can see around the room. Oh, I do them by the hundreds, by the thousands. My studio is crammed full of them. Take my studies of plants, for instance: there are studies and studies of architecture, the structure of plants, and all that. But I never copy these studies when I’m doing a painting. I never take a sketch and transfer it to the canvas. That would be such a bore; I like the nervous feeling when you’re creating a painting from nothing but your imagination and instinct. I like to think of painting as walking on a tightrope… the tension of it!

Do you work on one canvas at a time, or do you work simultaneously on several?

I don’t really work on one painting at a time. I work probably on… oh, 10, 20, 30, 40 paintings at the same time… You see, it takes an awfully long time to realize one’s potentials. Some painters feel that they have to finish a painting on the same day, or sometimes they just plod along until the painting is completed. Well, I just cannot work that way. I must work in stages, and that’s why I work in two phases. The first is the starting phase, which I consider an act of passion. It’s a tense, nervous stage for me: that long, long ligaw-tingin, just moving around and staring at this empty canvas aching to come to life. This goes on for days until the whole thing becomes a pain in the stomach. And then, I start in an abstract manner. Slowly, the shapes emerge and evolve into reality, or, anyway, my type of reality. I work on these canvases until I’m so saturated with them that I feel like throwing them out the window.

In the painting process, are your aesthetic decisions directed by emotional and intellectual forces or objective and subjective considerations?

I do certain things, I make certain decisions for which I cannot explain rationally. Why this shape? Why this color? I cannot listen to any voice other than my own.

Here, I see drawings of the barong-barong… Why do you think the barong-barong holds such an intense fascination for the Filipino painter?

Why? I wonder myself. I have exhibited these drawings of barong-barong in Paris, and they have elicited enormous curiosity. I suppose there’s the human element, for one. A reality too painful to think of: all these people huddled together, crowding each other under this frail roof, this almost derelict construction of planks, boards, and corrugated sheets. But aesthetically speaking, I think the barong-barong is one of the most beautiful things the Filipino has ever constructed spontaneously: an invention made out of desperate necessity. You have these planes that catch light: a reflecting plane. They’re almost like sequins, and the haphazard construction of patterns and shapes is rhythmic and animated. That’s what’s so lovely about the barong-barong.

Do you think that Philippine painting, to be genuinely Philippine, must depict Philippine subject matter?

There again, you use the word “must.” But why? One must not lead one’s emotions by the nose. Please take a look at my paintings of the coast of Brittany. Indeed, it is a French landscape. And consider my paintings of San Dionisio. Certainly, it is a Philippine landscape. What conclusions can we draw from this? I think that for a painter—whether he’s Filipino, French, or American—the most important thing is to paint what he thinks he wants to.

You have done for San Dionisio what [Carlos V.] Botong Francisco has done for Angono and Bencab for Bambang. Because of the painters who have recorded the landscape of these places, these locations are now more obstinately memorable. These artists used them, in fact, as

genus loci. It generates an emotional experience affected by the sight and smell of one particular place. It’s the stuff that makes for romantic painting—this concern for the particular, not the general.

I might also add that the nature of my painting is essentially nostalgic.

Nostalgic?

Yes, nostalgic. These things come to me now as afterthoughts. I don’t know if I am rationalizing my feelings. One evening, when I was having a chat with Ding Roces, I remarked that it had just struck me all of a sudden that the war—yes, the war—had shattered the dream-like quality of my life. I thought of all the anguish and the suffering, the catastrophe, and the horrible massacres. I don’t know, but I believe that it is through my paintings—romantic, you call them—that I can find it.

Are you using your art not only as a medium for personal expression but also as a means of escape? An opiate, perhaps?

That’s a rather harsh way of putting it, but I feel that, in general, most artists have a hard time adapting to… what? The reality of life? I believe that in any artistic creation, there is always an element of neurosis. It’s the only bridge we have left, the last refuge from a world of madness, insanity, and despair.

Once your paintings are finished, are you interested in them? Are you glad to see them go?

If I could have my way, I wouldn’t sell any paintings… not a scrap. I couldn’t afford my paintings!

Is there any painter who has had the most influence on your work?

No. I don’t think so. Instead, a specific culture has had the most significant influence on my work. By this, I refer to the culture of the Far East, which has profoundly impressed me. There isn’t any single artist whom I have wished to imitate, even in my earlier days. Why should I use a parallel and imitate the voice of Marlon Brando when I have my own?

Since your first one-man show in 1956 at the Galerie de la Maison des Beaux-Arts in Paris until now, you’ve had an impressive string of exhibitions. Tell me, as a veteran of these shows, how does it feel on opening night?

Still an agony, a bit of an agony. I am a very shy person. I have always been. Terrifyingly so. While studying in Rome, I wouldn’t dare go inside a restaurant. I was always so embarrassed then, as I could not speak Italian. Now that I can speak several languages, people rush to you during opening night talking in a babel of languages. Sometimes, I get so dizzy shifting from Spanish to French to Italian to English to Tagalog!

What would you consider the most significant painting you’ve ever done?

I would think the fresco painting I did for the Palazzo Dario in Venice. It’s one of the most beautiful palaces in Venice. As it is a national monument, I couldn’t just doodle anything on the wall, you understand. Let’s say it was an understanding between the architecture of Palazzo Dario and myself.

Your output has been terrific, with works ranging from paintings, drawings, and photography to the graphic arts, mosaics, and sculpture. You have also done quite a lot of work for the theater by way of stage sets and costumes…

Yes, quite. The last one I did was for Gian Carlo Menotti. I have worked mainly on operas and musicals.

How does your painting relate to stage design? What sort of conflict, if any, arises from the practice of the two?

Well, a set designer works in two ways: one is that he serves the piece, opera or ballet. The other is that he serves himself. I try to be in the middle of the road. To me, a set design is like a monumental painting come alive. My fresco and mural painting training has given me this approach to set design. I try very hard to serve the piece. You see, the thing is not to accept any old thing, any set commission that comes along. Sure, I could put in anything I fancy, but that would not be fair to the piece.

This question seems academic, but to whom is the artist’s first obligation?

To himself, of course! I don’t say that out of a narcissistic need. My paintings are like my fingerprints! If they are somebody else’s fingerprints, I have no business painting.

Have you, from childhood, always wanted to be a painter? Or did you become a painter by chance?

It was a most peculiar thing. Early on, I knew that I was highly dissatisfied with many things, and of course, I never did like my father’s business. I never did like any business at all. I was maladjusted, completely maladjusted. But then, as luck would have it, Alejandro Celis walked into my father’s shop one day wanting to show my father some of his paintings—there weren’t any galleries then, you see. Fortunately, my father liked the paintings. My father, in fact, had wanted me to take up design, furniture design, and all that. Anyway, the whole thing ended with Professor Celis giving me painting lessons at home in the evening. But there was a limit to what you can learn at home. I mean, I was painting without models, nude models, you know. So, Professor Celis suggested I study at the University of the Philippines. So, I started my studies at the UP as a “special student” because, as you know, at that time, to be a painter was a ridiculous thing.

You must be extremely fortunate to have parents who encouraged you in your artistic vocation.

I think, on the other hand, that parents should be careful about encouraging their children to pursue an artistic career. It’s one of the toughest lives possible.

I have always thought that Filipino parents discourage their children from taking art as a profession.

Well, they’re right to do so in many ways. It’s a whole life of endless sacrifices. People just don’t realize it. Take, for instance, the life of a ballet dancer. People think, wow, isn’t she lovely to look at, just prancing about? We have no idea at all of the punishing discipline a dancer must go through to hold or raise or stretch that arm at the right length and moment. It probably took her years and years of daily torture. Well, painting is this way, too. Perhaps worse even. Whereas a dancer needs only to interpret, a painter struggles to create.

Perhaps if parents considered painting a financially stable profession, they wouldn’t discourage their son or daughter from being a painter.

But it never is financially worthwhile!

Well, how can you say this? Your paintings command prices that are astronomical, to say the least.

But think of the effort; think of the hours of work a painter devotes to his art! When he holds an exhibition, he has to be a painter, PR man, and host.

How would you compare Paris’ art scene with New York?

The New York art scene is more active for good and bad reasons. Artists are launched like toothpaste and detergents; fashions and styles change to push people into buying. The market is like that in Detroit: you’ve got a new chromium and a new model; it doesn’t matter whether you’re ruining the countryside landscape. It doesn’t matter; you must have a new car every year. It’s really like killing the goose… But don’t get me wrong, I love New York. To a lesser degree, in Paris, you have the same kind of jungle. But I’d rather be poor than fall into the mafias of the big galleries because then you are under their power.

Which peculiar quality of Paris attracts you and a thousand others to work in this city?

The human scale. I feel I am not crushed by the city. Of course, like any other city, Paris is getting more polluted, and its pace is getting more hectic. Then, there’s the challenge of competing with 50,000 artists in a city where even the slightest recognition is a major victory.

Shall we say then that your roots are now in Paris?

Oh, no. My roots are in the Philippines. Let’s just say that the leaves are in Paris.

You have done most of your work in Paris or, in any case, out of the Philippines. Do you feel that you are somehow living in self-imposed exile?

Oh, most definitely not. I feel that I still live in the Philippines—through my paintings. My paintings, if I may say so myself, are probably among the most Filipino you can find.

Read the full interview in the book “Conversations on Philippine Art” by Cid Reyes, published by the Cultural Center of the Philippines.