Learning the lingua franca—‘lingua franca?!’

I remember growing up with “English-only” policies in the schools I attended. There were times when I had to pay one peso per Filipino word that I say, which would supposedly go to a class fund—but I was pre-pubescent, and had no knowledge of financial transparency, so I never knew (or cared to know) where that money went.

I was raised prioritizing English, and this meant I had a lot of difficulty speaking Filipino—or, at least, Tagalog. When I was in Grade 2, I was even asked to read in front of the class, and I pronounced “alas-2,” not as “alas-dos” but as “alas-two.”

Even today, I hear many Filipino parents speaking to their children in English, no doubt to prepare them for a globalized world. An English speaking child—an “Englisero”—is seen as smart. One who speaks English badly, with a thick Pinoy accent and too many grammatical mistakes is called “barok,” which for some time, I thought was an archaic word that meant “broken.”

But actually, Barok was a caveman-like character from a 1970s comic strip. Essentially, whether we are aware of it or not, we are calling all bad English speakers uneducated and primitive—that is, like Barok the caveman.

Knowledge (and language) is power

English is today’s main choice for commerce, education, and communication (what we call “lingua franca”) and is the direct result of historical domination. After all, you have to know the language of whoever you are trying to trade goods with.

In fact, the term “lingua franca” was used to refer to a mix of languages in Western Europe, which was once in vogue many centuries ago. It is not impossible for the world’s most-used language to shift to a different one eventually, should new powers dominate economics, politics, and popular media.

The search for a national language

For a long time now, the Philippines has attempted to standardize a national language. Many Filipinos are bilingual—at least with English and Tagalog. Even more are tri- or multilingual. In addition to the first two, they are also fluent in their mother tongue. Tagalog, however, dominates as the foundation—likely because of political influence, from the early revolutionaries to those who sat at the table that decided on the national Philippine language. In fact, most of our movies and reading materials are in Tagalog to this day.

It makes sense, then, that this is seen as a form of domination by “Imperial Manila.”

But can we really have a fairly representative national language? We have almost 200 regional languages—not merely “dialects,” because two distant ethnolinguistic groups will likely not be able to understand each other. There are a lot of words from various regions that are in common use today, but a mixed, pan-Philippine language is just too bizarre to make any real sense. It would have the words, but not the depth.

Tagalog itself is already quite an odd mix, having absorbed many Sanskrit, Chinese, and Spanish influences early on. There are even English words that are spelled as pronounced, such as “nars” and “kompyuter.” We also use English words with our own particular meanings, such “commute,” “overacting (OA),” and “comfort room.”

I like to think that if we, as Filipinos, want a useful national language, it would be ideal for regional terms to fill the gaps of Tagalog in its imperfect attempt to give us access to a collective cultural consciousness. Even more ideal is that we become bilingual—not necessarily in English and Tagalog, but in a standardized Filipino (Tagalog-based or otherwise) and whatever our regional mother tongue is.

Let English handle itself, and let the globalized learn the cosmopolitan ways of the world on their own. But let us learn to speak to each other and share the old stories the way they were meant to be sung.

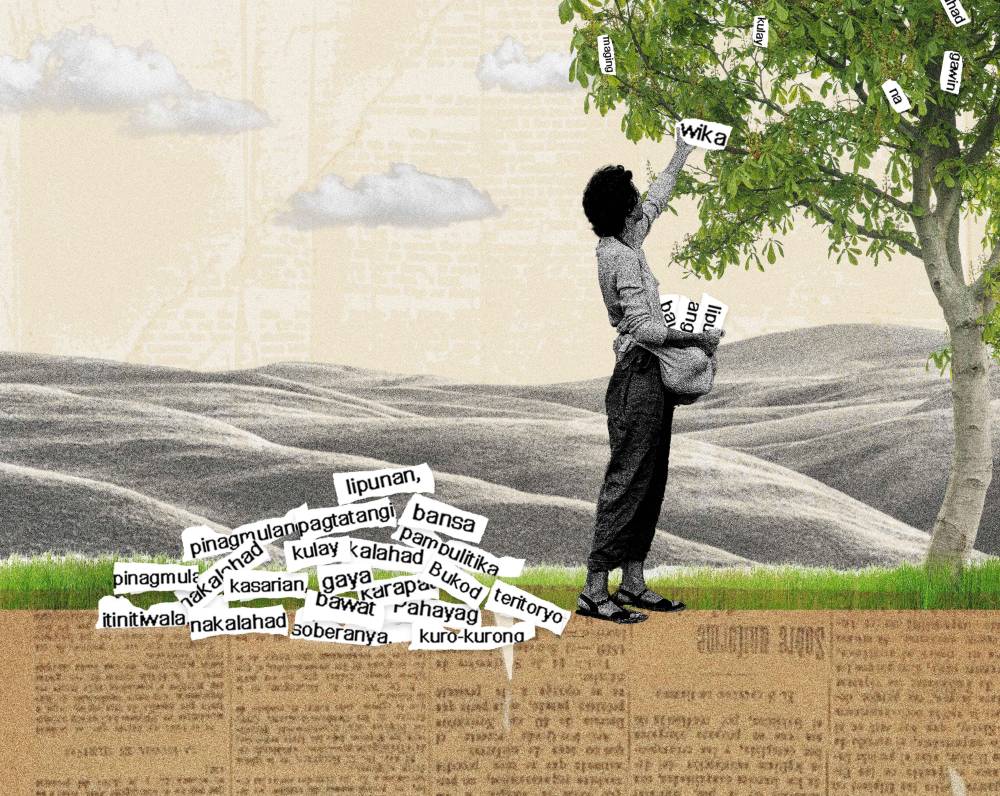

More than words

This Buwan ng mga Wikang Pambansa, it would be good to remember that language is really just a system of symbols and sounds. Actually, by itself, it is useless. But as a whole, it is a system of symbols that represent important human experiences. And when these languages are forcefully erased, or the people who speak it die out, we are also losing our access to these experiences.

For example, I can explain something in English, and it can be understood by most people (that is why I wrote this in English), but it will never capture the same humor, comfort, and spiritual pleasure of my native tongue.

The mother tongue evokes the warmth of being held by a parent. It is the poetry of a lover and the unbridled wrath of an enemy. How much better it is to say, for example, “Ginahigugma taka” (I love you) or “Akin ka lang at sa iyo lang ako” (I am yours, and you are mine), or even “Giatay ka, yawa” (Damn you, devil), rather than their English equivalents—at least for native speakers.

Language is a cultural map of our psychology. This is why Filipino scholars once turned to the terms used by the everyday person in order to create a technical vocabulary for Filipino psychology (e.g. kapwa, hiya, pakikiramdam, etc.).

Hearing the songbird melody of Hiligaynon transports me to my grandfather’s house, where the cool Silaynon breeze always smells like sugar. When I teach and give talks about psychology and folklore in Tagalog or Taglish rather than in full English, any important topic feels more true and more relevant—even more so when I mention regional equivalents in Ilokano or Cebuano. I see eyes light up when they realize, “Ah yes, that is exactly what it is!”

And what an amusing thing it is, when I travel with loved ones to a foreign country, and we chance upon a fellow Filipino. We will likely never meet again, but a shared comment and a laugh just reminds me that we are at home, wherever we are around the world.