Letizia Constantino, her letters, and her grandson

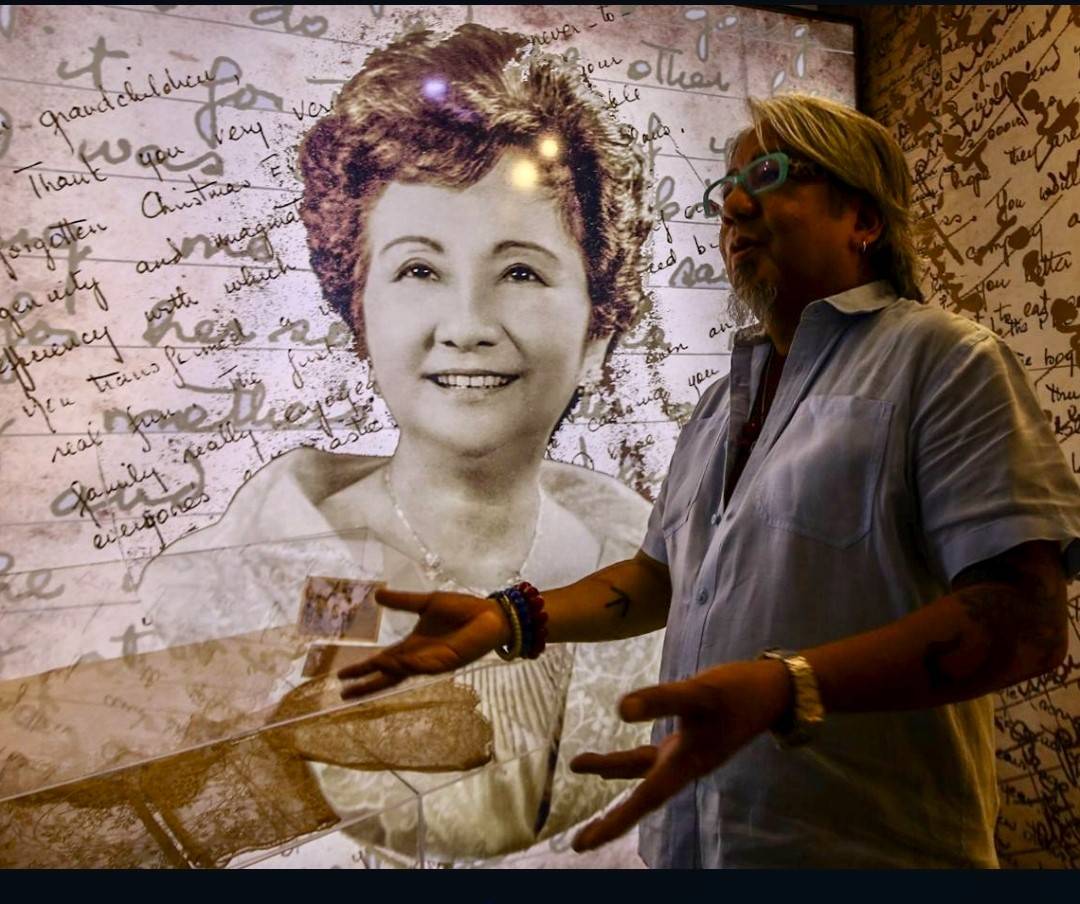

A n invitation from Renato Redentor “Red” Constantino to view the exhibit “Letizia: A Life in Letters” slipped into my DM shortly before Holy Week. (Red and I were classmates at Jose Abad Santos Memorial School or JASMS, which used to occupy a wide stretch of land along Edsa.) The exhibit celebrates Letizia Constantino’s 105th birth anniversary and runs until May 30 at the Constantino Foundation’s Linangan Gallery, 38A Panay Ave. in Quezon City.

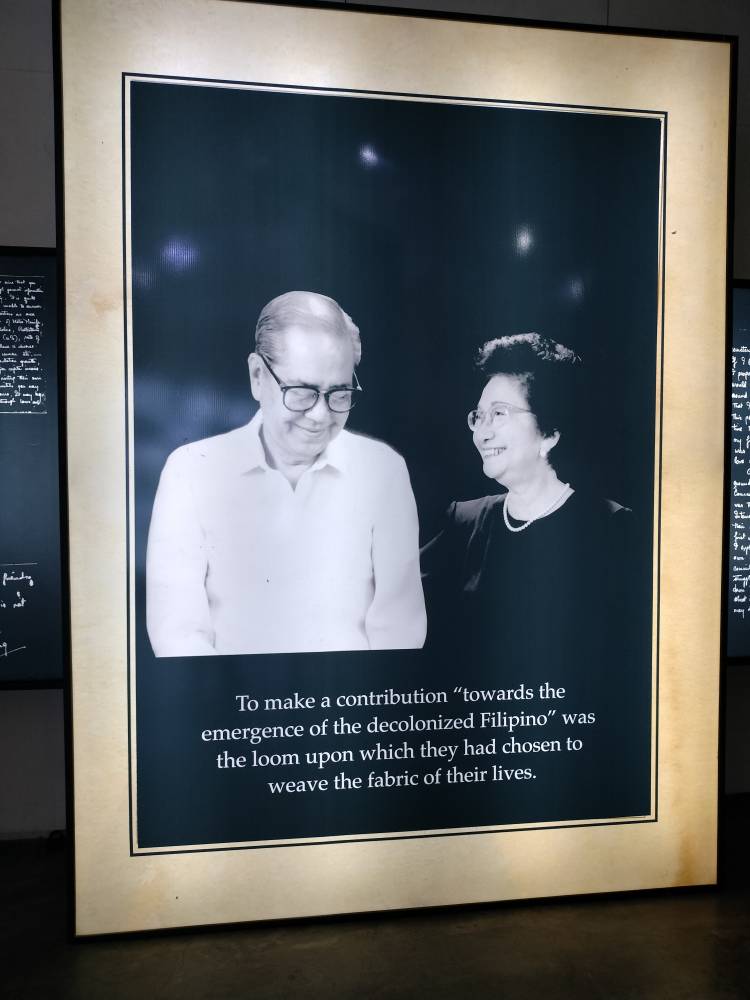

Letizia, who died in 2016 at 96, was familiar, yet she wasn’t. We knew her only according to her relations. She was Red’s grandmother. And she was married to the historian Renato Constantino and his collaborator in “The Past Revisited.”

Looking at her letters, manuscripts, and notebooks on a Tuesday morning early in May stirred a faint feeling of nostalgia and a budding understanding of her as her own person, while finding a common ground in writing.

From her memorabilia, I learned that Letizia’s interest lay in history, literature, music, and writing. She loved conversing with people and writing letters to friends and family. She wrote in her diaries and notebooks; she wrote essays and annual newsletters, which kept family and friends in the loop on the “achievements of [her] growing family.” All are displayed in separate vitrines around the gallery.

Her letters are reminiscent of Jose Rizal detailing his life abroad and in exile in his letters to his family and friends. Her newsletters are similar to what my maternal relatives sent during the holidays from the United States decades ago.

Letizia kept “records of household purchases, books and pamphlets sold, income from apartments she and Renato managed,” as well as letters from her husband dating from the 1930s. She wrote annotations on news and articles clipped from weekly magazines and newspapers, storing a set of clippings for her own file and sending the rest to her husband Renato and her children and grandchildren with notes attached on grammar, political angles, criticism, and praise, etc.

One reads: “For eight decades, Letizia recorded everything in notebooks and journals, including expenses, [raffles she organized, the] winners and prizes, gifts to and received from friends and family, repairs, and tasks due. What is on display is less than 1 percent of accounts she kept and filed.”

Affinity

The vitrines with stacks of bound index cards and old notebooks lead me to think nostalgically about my school days. Index cards and notebooks (Corona was a popular brand) were indispensable for Gen X, my generation. It was the same for Letizia and Renato, who wrote and organized the tasks they needed their children to do on index cards while writing their two-volume history books, “The Past Revisited” and “The Continuing Past.” The children were the late siblings Renato “RC” Jr. and Karina, and their respective spouses, Lourdes and the sociologist Randy David.

Gen Xers wrote notes on index cards of varying sizes for research papers in high school and university. When I was teaching English literature at an international school in Indonesia, the index card was the same research tool I wanted my own students to use for their research paper, a final requirement in my class. Oddly, index cards were unheard of there!

Card catalogs are part of the nostalgia. A fifth label states that Letizia and Renato, in the precomputer era, used card catalogs to arrange their books, notes, and research.

A vitrine with CDs reveals another interesting side to Letizia. My thoughts circle back to the huge didactic text at the gallery entrance that quotes author Rosalinda Ofreneo from the book “Letty at Eighty”: “She could have been a great concert pianist but love steered her to another direction not as glamorous but no less demanding. Today, we are all the richer for that twist of fate, from piano to pen.”

The CDs contain one of the many recitals of a classically trained pianist, put together by her grandchildren: CP recorded Letizia playing the piano, Kara digitized them, and Ninel made the CD covers.

Writing space

A desk illuminated by a collage of video footage sits at the back of the exhibit hall. If musicians have their instruments, writers have their desks. Letizia’s desk has two drawers, a portable “vintage” index card holder, a lamp, and ample elbow room for comfortable scribbling. (The desk was Red’s favorite, too, he said on Messenger, adding that the desk and chair were what his grandmother—affectionately known as “Dada Ming”—used for a long time.)

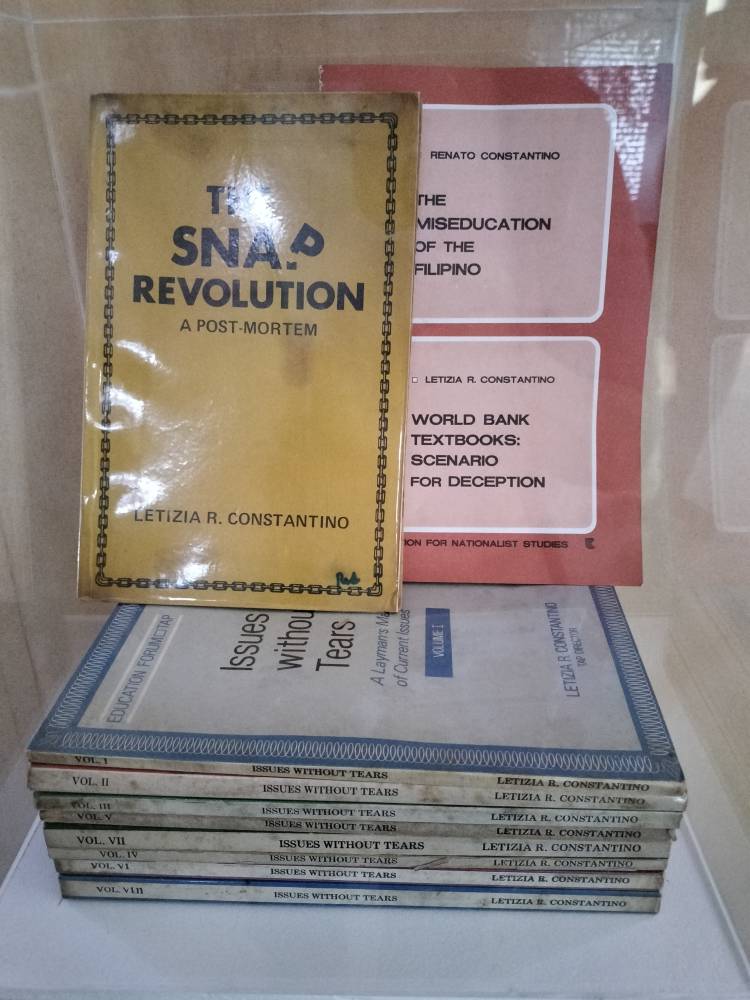

I see Letizia in my mind’s eye writing to her granddaughter Ninel in Hong Kong and to her grandson Carlos David in Escondido Village in Stanford University. I see her again writing an essay, editing her series “Issues Without Tears,” and recording recipes and the meals she served to guests. She was meticulous about repasts served at her house, states an object label on a box of recipes.

It is a small thrill to know that Letizia wrote in longhand (like my father did) and, thoroughly old-school, had her works typed. Her manuscripts and letters hurled me back to my own typing class with Ms. Amy Manangbao. Typing class was “music class”—clickety-clack against the platen of the keys, click of the line space lever, and ding of the bell by the typists during the drills.

Letizia was a methodical writer. “She would always write the first draft of her essays, letters, and speeches by hand. The second draft would often remain handwritten, which she would edit before having the final version typed out. She kept all the original first drafts filed with the final copy,” states the label of the vitrine holding her typed speech dated Sept. 24, 1978, for The Philippine Booklovers Society.

Educator

Letizia worked closely with teachers and members of the Education Forum, explains a label below a vitrine displaying “Issues without Tears” and “The Snap Revolution.” She organized, wrote, and edited the contributed essays in “Issues without Tears” that discussed the social, economic, and political issues plaguing the Philippines in the early 1980s from a historical perspective.

She and her husband Renato rejected the traditional colonial approach to Philippine history, strongly advocating for a Philippine historiography or a Filipino perspective on the struggle against oppressors. As the couple saw it, Filipinos had to understand their historical past in bringing about a just society.

That Letizia was a teacher is a detail I learn from the exhibition pamphlet that carries a reprint of her Aug. 20, 1992 letter to Red. The letter was in response to his admission of his fascination with poetry, which contrasted with her interests. She was not into poetry, despite having taught poetry analysis/appreciation many years ago.

Interestingly, Red’s confession coincided with her effort, as she wrote, “To exercise a rapidly deteriorating memory, I’ve been memorizing poetry and reciting a couple of them before sleeping, in lieu of other people’s Hail Marys, both sleep-inducing because they shut out other thoughts.” Wittily, she pointed out the contradictions of “poetry as mental stimulus and as soporific, but no matter, life is full of contradictions.”

Memorizing Carl Sandburg’s “I Am the People, the Mob,” Letizia shared it with Red because it was “politics in poetry and poetical politics.” But she cautioned him from reading the rest of the letter until he had reread the poem slowly and savored it.

Letizia’s letter to Red transported me to my past literature classes, and I imagined Letizia as my teacher. She outlined in it her possible discussion of Sandburg’s poem in class, beginning with locating him within the context of history and his own milieu (“Sandburg was an American poet born in Illinois in 1878 to humble Swedish immigrants,” she wrote).

Next, as a literary critic, she would have discussed the two Sandburgs—the “imagist” and the “muscular.” Rounding up the discussion, she listed questions for further rumination, like: “In the title, why did the poet choose to call the people the mob?” Or: “What are ‘a few red drops for history to remember’?”

She concluded the “lecture” with the line “end of lesson,” signing off as Dada Ming.

Reacquaintance

Red liking poetry was a revelation to me. In high school, could we have discussed literature, poets, and novelists? Was it uncool for a recalcitrant teenager like himself to talk about literature with my clique?

We went to the same school, but belonged to different cliques and classes. Teachers didn’t need to keep a stern eye on my clique (the so-called “behaved” students), unlike Red and his gang—in their trademark jeans, T-shirts, and Chucks—who were perpetually on the teachers’ radar. We didn’t talk much, whether in school or while riding Mang Mark’s school bus home.

There was radio silence after graduation, until seven years ago when a high school buddy took me to Red’s old bar at the Cubao Expo and we gabbed the night away. We met again when a former flatmate organized lunch two years ago on Morato, and again when I attended his father’s wake last year.

Like his grandmother, I’m not fully into poetry but I’m partial to Pablo Neruda’s lines, Shakespeare’s sonnets, and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven.” What would Red have said?

“Letizia: A Life in Letters” is a strong lesson on the importance of honing intelligence for a generation of students taught by memes, misinformation, and fake news. There’s no disregarding the figures on the Filipinos’ literacy level recited by Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian: 24.86 million Filipinos, age 10 to 64, are functionally illiterate, and 5.86 million Filipinos in the same age group are basically illiterate.

Personally, it was my reintroduction to a woman who, beyond being a wife and a grandmother, was a scholar, nationalist, and pianist. Her letters and essays showed up the country’s ineffective educational system. Would her letters and essays been understood given the widespread illiteracy? She read, wrote, and discussed issues of major importance; she imparted wisdom and instilled a desire to pursue knowledge in people.

And the exhibit reconnected me with an ex-classmate who appears to be a chip off the old block—writing, reading and fighting for what’s right, like his Dada Ming.