Locating the ‘Tropics’ in “A World of Islands”

On the third floor galleries of the Ateneo Art Gallery, a world of islands flows in between portrayals of the Philippine archipelago—conveying various perspectives, mostly in sculpture or video, with not a traditional painting in sight.

Curated by Ligaya Salazar, “A World of Islands: On Palms, Storms & Coconuts” opened last Feb. 1 and runs until May 24. First presented at the Stanley Picker Gallery, Kingston University London, the project began as an investigation into the movement of Indigenous knowledge, materials, and people across oceans. Underlying it are interrogations of the myths of tropical utopia and dystopia, the legacies of colonialism, and the environmental realities of the tropics.

Born in the Philippines, curator Salazar left the country at the age of seven during the first Marcos regime. With a German mother and Filipino father, she studied in Germany before moving to the UK, where she built a long academic and curatorial career, teaching across universities, and working for nearly a decade as curator of Contemporary Practice at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and later leading the university gallery program at the University of the Arts London. She now works as an independent practitioner.

“I spent a lot of time in libraries, lost in researching Indigenous materials,” Salazar said during the preview. “I got stuck on coconuts, palms, and pineapples, and specifically how they moved between the Philippines and Mexico. That’s the origin of the title but also the thinking behind the approach to the exhibition.”

This Philippine iteration now expands the conversation with these eight artists, four from the archipelago and four from the global Filipino diaspora, offering explorations that show deeper nuance in the representation of Filipino artists.

Water, memory, and diaspora

The exhibition opens with Derek Tumala’s “Vanishing Points,” a three-channel video installation that transforms memory into meditative digital waterscapes. Tumala expounds how, “The sea is a meditative place for me. When I look at it, I imagine how beautiful, but also how dangerous it is.”

Replayed in a loop from day to night, Tumala states the 3D-modeled water is “about cycles rather than time,” complemented by a soundscape composed by concept collaborator Mario Consunji.

Further in are three screens showing the material-based video installation “Memory Debris | A Tourist in My Mother’s Land by Kim Sacay Chin. Born to a mother from Ormoc, Leyte, and a father with Guangdong heritage from Kingston, Jamaica, at the preview, she describes her work as “an honest love letter to intergenerational resilience,” rooted in her relationship with her mother, a migrant parent. “My mum’s own history… her strength has brought me the ability to choose to be an artist,” Sacay Chin shares. “Using art-making and different visual tools as symbols [is a way] to find a common ground—to show where we overlap and where we differentiate.”

Water also plays a central role in the film, operating as both image and metaphor “as a sort of vehicle of fluidity of memory… and how time is non-linear, and that also mirrors neurodivergence.”

Just months ago, you might also remember how Cebu was struck by back-to-back earthquakes and typhoons. Ronyel Compra found himself at the center of both storm and fault line in his hometown of Bogo. His installation, constructed from Molave wood and informed by banca-making techniques, draws directly from the material and emotional aftermath of these events.

“This work is from trees that have fallen after the typhoon,” Compra shares. “It reminds me of growing up in this specific childhood place,” he says. Pointing to the dowels in between the wood, he highlights how centuries-old inter-island building techniques are reworked into a contemporary sculptural language. Titled “Playing in Reverse,” the installation also plays on the words “playing in rivers,” gesturing to cycles of destruction and rebuilding, as well as the reversal of time.

Meanwhile, Nice Buenaventura brings actual water into the gallery space. Her featured work, “High Tide Atlas (Gaian Assembly XVIII),” jumps off a piece she first developed several years ago, a painting based on a highly enlarged, obscured reproduction of a colonial-era book about the Philippines.

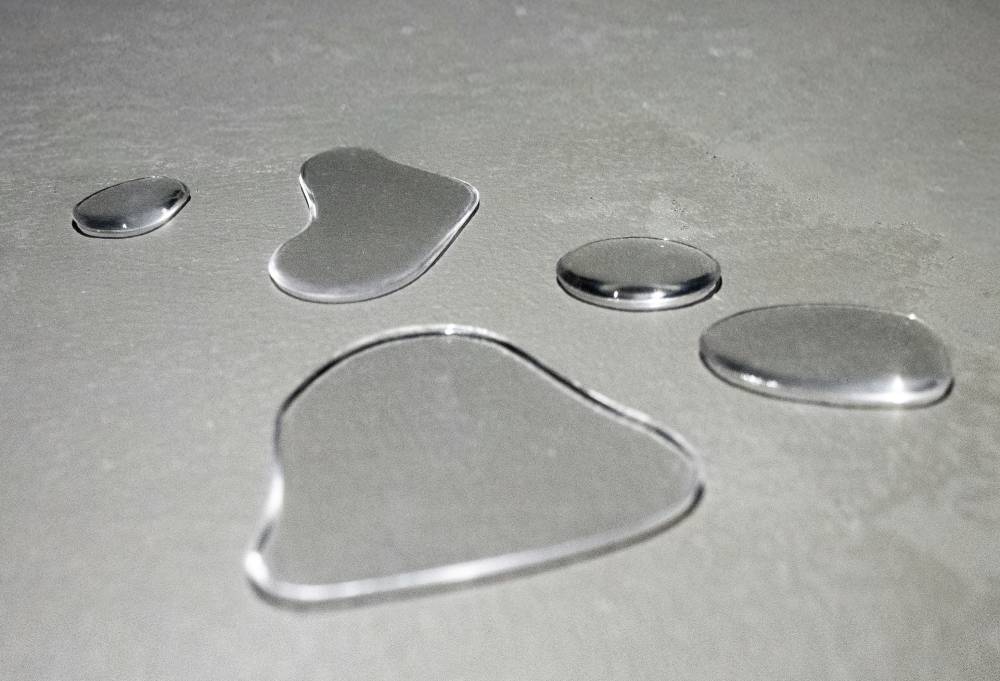

“What you’re looking at here is a series of Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) trays filled with still water, up to the point where it has a perfect meniscus,” Salazar elucidated. While the work takes its source from the noise created by an enlarged photocopy, it’s also a “kind of water archipelago, but it could also appear as a puddle on the ground,” she said, evoking the omnipresent threat of floods, storms, and environmental instability. Also a durational work, the water evaporates and is periodically refilled during the four-month run of the exhibition.

Place, craft, and climate

In a video work that touches on place, Stephanie Comilang explores experiences of migration and exploration in what she calls “science fiction documentaries,” weaving together people, memory, politics, nature, and ritual. The Filipino-Canadian artist presents a video work, “How to Make Painting from Memory,” which documents a community of Thai women in Berlin while showing connections to the Thai people’s practice of Bayanihan, with footage of communities carrying relatives’ homes from place to place.

Having immersed herself in various communities for the production of her work, Carol Anne McChrystal’s series of sculptural mats called “Pasalubong #1 (Trapal)” is crafted from found plastics, polyethylene tarp, grommets, plastic bags, cordage, and complemented by concrete. Through these sculptures, she explores the relationship between colonial histories and climate catastrophe, in archipelagic thinking that engages with how environmental degradation intersects with diasporic memory and labor. The socially-engaged artist based in Los Angeles was born to a mother from Tondo and a father from Dublin.

Meanwhile, another diasporic artist, Alex Quicho, speculates on maritime sovereignty and environmental futures through computer-generated imagery (CGI) renderings of artificial islands in the West Philippine Sea. “Alley to Heaven” imagines a fictional future in which an island has been overtaken by genetically engineered corals, its terrain revealed through a guided tour led by a digital avatar. Drawing from gaming culture and science-fiction aesthetics, the work interrogates contemporary modes of seeing, probing the uneasy tension between territorial desire, ecological fantasy, and dystopian futures.

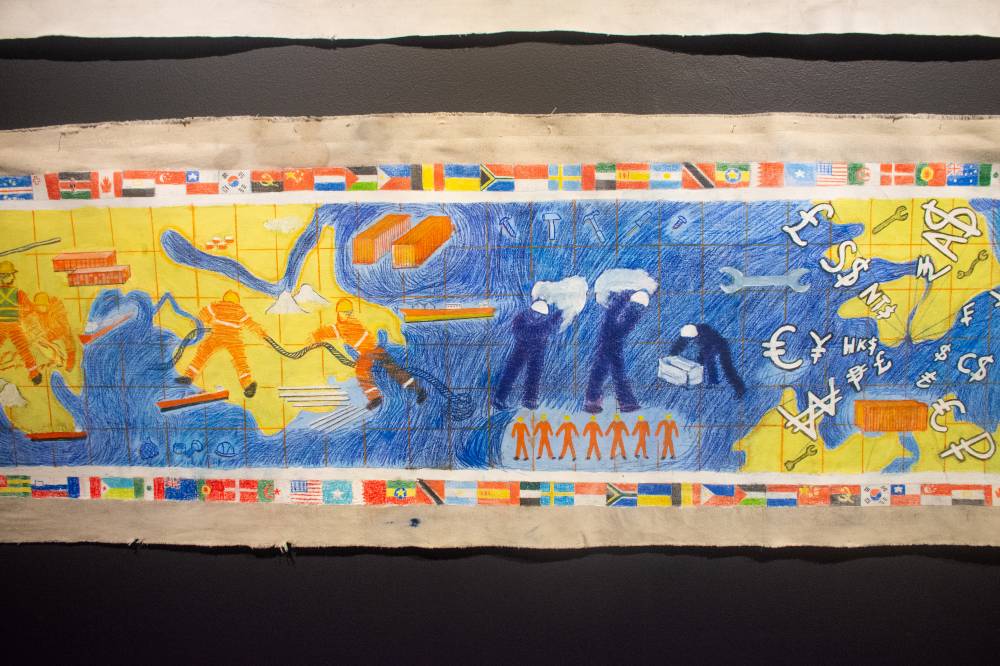

For the final work in the exhibition, a work on paper, Joar Songcuya’s paintings draw from a decade spent at sea, portraying Filipino seafarers navigating both the physical dangers and political precarity of global waters. A self-taught artist, Songcuya previously worked as an engineer on large trading ships for ten years—an experience that mirrors the often harsh realities of overseas Filipino workers.

His drawings stretch across six long scrolls, combining scenes of real events, such as ship fires, with more subjective impressions of the sea, like the people he encountered. Throughout are symbols of restriction, showing national flags of countries he has sailed past but never set foot in, due to the absence of visas and the constraints imposed on seafarers who remain bound to their ships.

Songcuya’s relationship to migration is also personal. His mother was herself an overseas Filipino worker (OFW), working in Kuwait and other countries, returning home only once or twice a year but regularly sending him colored pencils from abroad. These early gestures inform his practice today.

A shared future

Simultaneously isolated and interconnected, these works assemble a free-flowing dialogue on the archipelago that brings to mind the underlying politics of labor, ecological life, and privilege.

“We want to relocate the agency in the tropical narrative, unpick clichés, and consider how interconnected our futures are as a world of islands,” the curator says.

In this meditation on our very own country as both a lived and imagined space, going through this exhibition feels like traveling through both mythic and very tangible realities today, rising and falling like a wave through stories that are both personal and universal, to which we can all relate.