Mich Dulce’s hats give voice to a decolonial dialogue

The human head was the location of animated culture-making,” writes cultural critic Marian Pastor Roces, reflecting on Philippine headgear traditions that once spoke of ritual, self-identity, society, and the past.

Mich Dulce takes that inheritance into the present with her exhibition “Nagsasalitang Ulo (Talking Heads).” As Dulce comments on culture through headwear at Finale Art File, the exhibit opens to the public on Sept. 5, transforming millinery into sculptural pieces, and making hats speak again—this time in a distinctly Filipino language.

The title nods to Pastor Roces’ essay, a foundational text for Dulce’s concept. “It was one of the core texts that influenced the show,” she says. “I wanted to think about the role my culture plays in millinery.”

Decolonizing the hat

Dulce recalls her early work in millinery about 15 years ago in Milan, when she discovered how sinamay, the abaca fabric woven in the Philippines, was very much a staple in the international hat trade.

Now based in the UK, the world-renowned Filipino hatmaker has many accomplishments under her belt. She has worked with Noel Stewart on collections for Balenciaga and Saint Laurent. Under Stewart, Dulce also worked for theater, designing hats for shows like “Cabaret,” “Phantom of the Opera,” and “Fiddler on the Roof.” Today, she serves as an industry mentor for Chanel’s Métiers d’Art Millinery Fellowship with The King’s Foundation, a program of King Charles to preserve the craft of millinery in the UK.

Trained by the West and passing on that knowledge to British milliners at present, Dulce shares how she came to the stark realization that she is deeply immersed in “a very white, very European” system. And from her positionality, she began to question her place in millinery’s canon.

“Traditionally, my work is about using Filipino materials,” she explains. “But maybe it’s not enough to bring just the material to the rest of the world. I wanted to think about what the Filipino form is—if we’re not thinking about fedoras, boaters, or berets, what are the shapes that come from our culture, our natural geography, our traditions?”

The result, she says, is “a reversal.” “It’s using Western craft to create a body of work inspired by the Philippines rather than another part of the world.” She calls it the “decolonization of hats,” as suggested by Erwin Romulo.

“What are the Filipino forms and shapes within our natural geography?” she asks. “Within our culture and our different traditions, what are the shapes that can give rise to a definition of Filipino contemporary millinery—without thinking of the external codes?”

Not so wearable, more sculptural

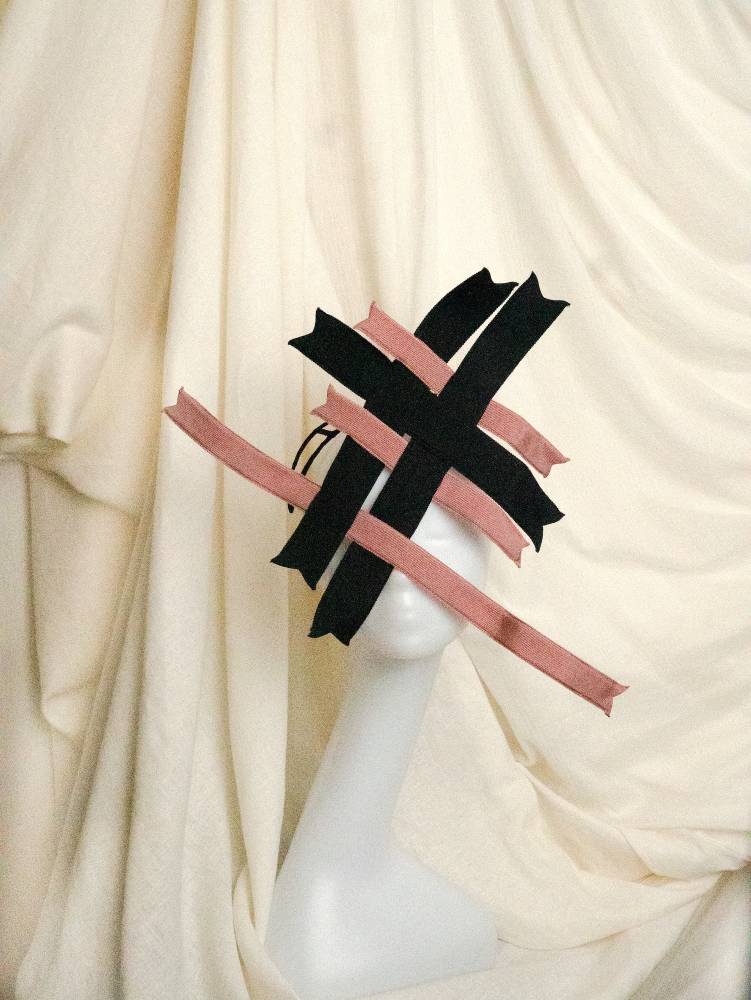

Dulce clarifies that “Nagsasalitang Ulo” is not a fashion collection. “They’re not wearable pieces. I mean, you can put them on your head and they will stay on, but they’re bordering toward sculpture,” she explains.

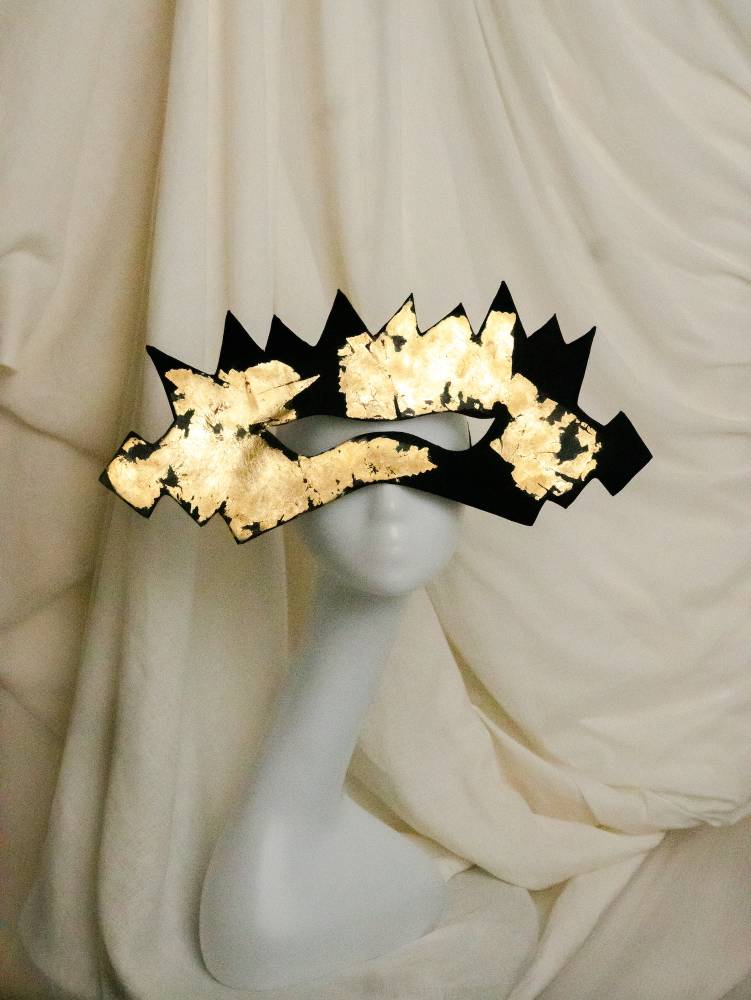

Resisting functionality in favor of meaning, many of the pieces translate aspects from the different cultures around the Philippines using age-old millinery techniques.

Echoing the protective nipa roofs of the Bahay Kubo, the silhouettes of this piece slope downward over the head, the “Banaue Rice Terraces” is a particularly striking sculptural work, echoing the lush green staircase-like form of the paddies. From Batanes, the Ivatan people are known for their distinctive headpiece called the “Vakul,” stretching down to the knees and made of vuyavuy palm that protects farmers from both sun and rain. In Dulce’s rendition, she translates the abaca and palm fiber into a shorter, stylish piece.

She remakes the Ilocano Tabungaw hat, made of traditional gourds, by adjusting the shape into a deeper, more dramatic dome. Taking from the fronds typically used in the Catholic ritual of Palm Sunday, she translates the blessed branches into a flat, wide, minimalist crown with geometric patterns.

Looking toward ancient, pre-colonial traditions, she creates a truly sculptural piece that echoes the gold death masks used in 15th-century Cebu—a mask of gold placed over the face’s orifices to ward off spirits.

Among the hats that channel aesthetic beauty is the black-colored “Samar,” inspired by the limestone formations in Biri Island, emulating the waves and storms with that same dramatic bearing.

To ground these transformations, Dulce stages the labor itself in the tall gallery space. At the center is a recreated milliner’s workroom that displays hand-carved wood blocks, scissors, and raw materials. This aims to remind viewers of the research and craft that goes into the repetitive, meticulous hat-making process of blocking and shaping. To accompany the exhibition, Dulce has also created 25 editions of a pair of signed and numbered prints.

At the preliminary opening, guests also sampled regional dishes by chef Gen Gerodias, paired with cocktails featuring Santa Ana Gin, with flavors that moved through regions, just as the hats do.

Looking forward

While the exhibit mines the past, Dulce’s ambition looks forward, expressing a dream where designers commission milliners on the regular. She notes, “In 15 years, the only fashion designer who’s ever commissioned me is Ino Sotto.”

As for everyday hat-wearing? “I dream of a resurgence,” she admits, “but it’s hard to prioritize hats during a cost-of-living crisis.”

So where is hat-making going in “Nagsasalitang Ulo?” It’s as Pastor Roces wrote, “The direction of growth eludes prediction, [yet] these heads still talk symbolically, over and above political speech.”

As the different elements of headwear from around the Philippines coalesce into one show, for Dulce, “Nagsasalitang Ulo” marks a convergence. “I’ve always separated my artistic processes and pursuits from my fashion work. This is the first show when they’re both together,” she says. “It’s still autobiography, still confessional… still identity politics.”

“In terms of storytelling, my role as a milliner was always to draw attention to the fact that we’re not just suppliers,” Dulce asserts. “We’re not just the providers of sinamay for the rest of the world… But rather, we (Filipinos) have our own artistic talents.”

On Sept. 6, Dulce sits down with Pastor Roces for an artist talk, moderated by Erwin Romulo. A fitting part of a show that continues the conversation Pastor Roces began: if heads once spoke in gourds or salakots, then Dulce’s hats speak up again now—sharp, insurgent, and undeniably Filipino.

“Nagsasalitang Ulo” runs from Sept. 5 to 27, 2025 at the Tall Gallery, Finale Art File, La Fuerza Compound, Warehouse 17, 2241 Chino Roces Ave. Makati City. An artist talk with Mich Dulce and Marian Pastor Roces, moderated by Erwin Romulo, will be held on Sept. 6, 2025 at 3 p.m.