‘Museums’ from the heart of Filipinos in Italy

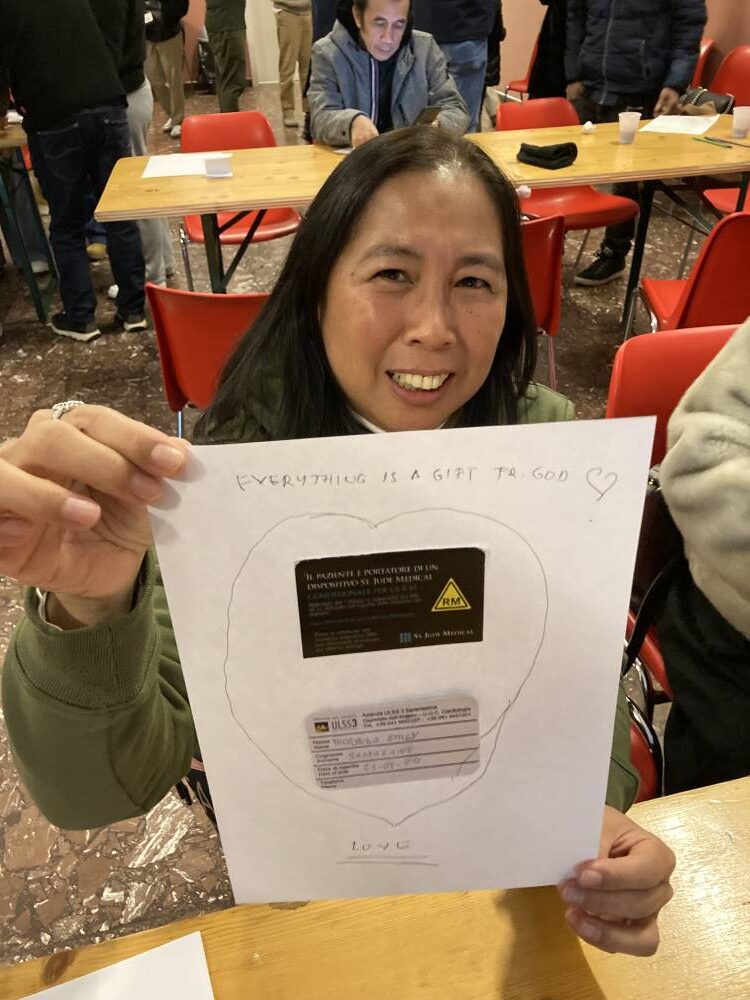

On a chilly night in Mestre, an administrative division or comune in the Veneto region of Italy, longtime resident but Philippine-born Rinda Sangalang showed me two cards she had attached to a piece of paper to stick on a wall. These cards had given the 32-year-old access to treatment for both breast cancer and a cardiac arrest that left her in a coma for five days. The cards were reminders of her survivorship, the beaming Sangalang said; when she noticed the tattoo on my forearm that said “Everything is a gift,” she appropriated the line and wrote, “Everything is God’s gift.”

It was a memorable first encounter for the even more memorable closing collateral activity of the Philippine participation in the 60th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, “Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere,” held from April 20 to Nov. 24, 2024 at the Giardini and the Arsenale in Venice. The Philippine Pavilion was titled “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/ Waiting just behind the curtain of this age,” by artist Mark Salvatus, and curated by Carlos Quijon Jr. It was a multilayered, universal, yet very Filipino interplay of images, sounds, sculpture, light and shadow, and historical references that connected to contemporary experience. The Philippine participation at the Venice Biennale is a collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA), and the Office of Sen. Loren Legarda.

Instead of a regular finissage, however, Quijon, Salvatus, and the Philippine Arts in Venice Biennale (PAVB) Coordinating Committee decided that, instead of waiting for Filipinos from other parts of Italy to come see the show, they would bring the exhibit to them. Inspired by the meanderings of Filipino religious leader Apolinario de la Cruz, a.k.a. Hermano Puli, born in the same place as Salvatus (Lucban, Quezon), and whose writings and beliefs inspired the exhibit’s title, the Lakaran Lecture-Workshop Series delivered a message from PAVB patron and moving force Sen. Loren Legarda, lectures by both Quijon and Salvatus, and a workshop activity that was by turns poignant and hilarious, to Filipino communities in Mestre, Ferrara, Napoli (Naples), Belluno, and Udine.

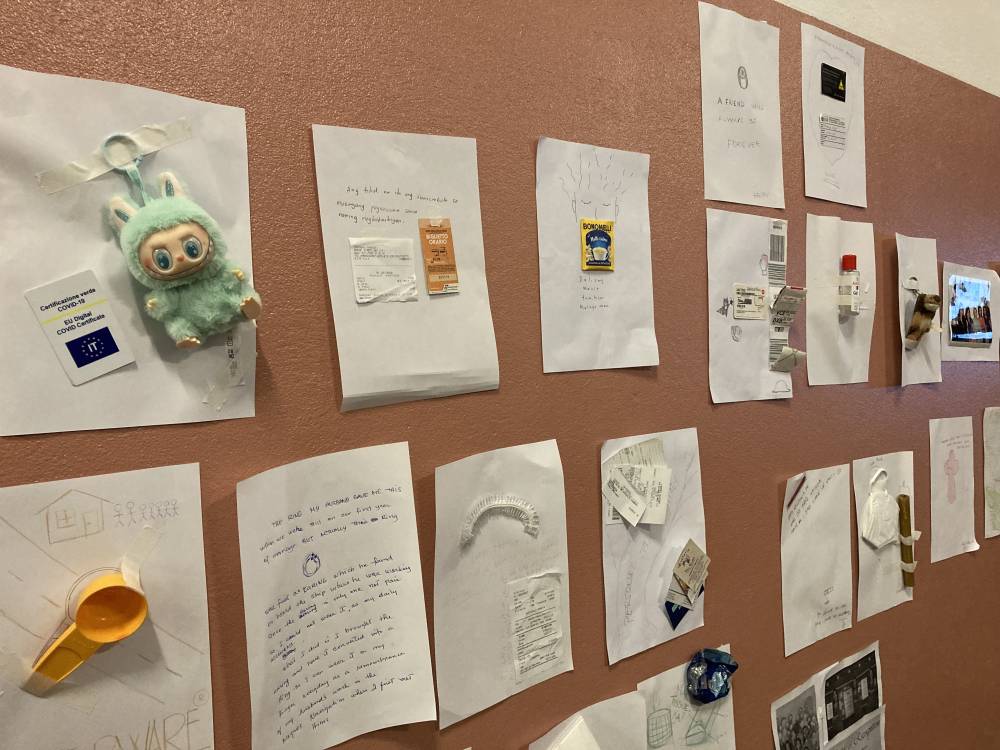

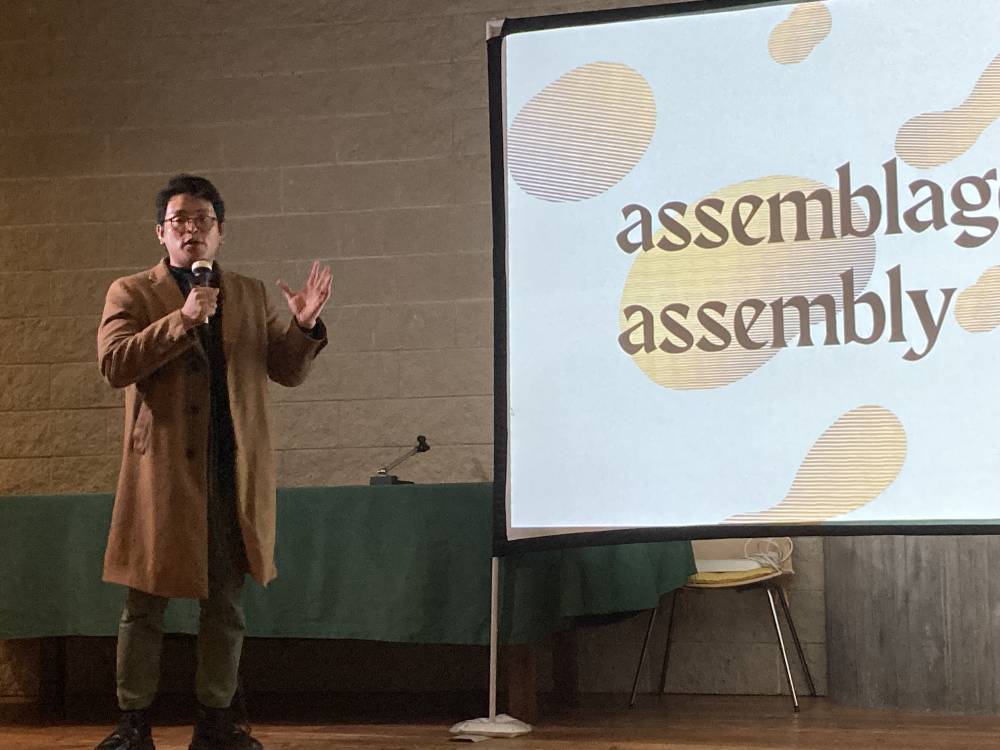

In each of the locations, communities gave warm welcomes as Quijon discussed the exhibition concept, Salvatus talked about his artistic process, and the last half hour or so would be dedicated to the workshop. Participants were preinstructed to bring something of value to them to display in a “Museo.” Thus, like Sangalang, people had photographs, talismans, letters, tickets, ID cards, and more. It was a powerful illustration of what Quijon referred to as the juxtaposition of assemblage—“a form of art where the artist gets existing, unrelated things, and relates them”—and assembly, the gathering of people.

The Filipino Community of Venice Terraferma in Mestre counts some 4,000 members, who were “excited about this project, especially when they heard we should bring personal things,” revealed president Joey Esteban. Quijon showed a short video of the exhibit, and asked “how a pavilion could represent the Philippines in its entirety, in an international context, without just thinking of Manila.” He reminded all that viewing art remained a personal experience: “When you experience the pavilion, you should still have some kind of takeaway, even if you’re not used to seeing art.”

Citing some interesting research on hometown musical bands, especially since Salvatus’ installation included “stones” made of resin embedded with actual, used musical instruments, Quijon discovered how the Philippines had long been a source of world-class professional musicians even in the 19th century. In other words, our OFWs were in demand even then.

‘Preserving the imagination’

Salvatus, meanwhile, began with a picture of the view of Mt. Banahaw from his window, and how his earliest exposure to art came from the annual Pahiyas Festival in his hometown. His first forays were into street art, such as from 2007 to 2012, when he engaged in his “Wrapped: Traces” project, from the streets of Manila, Angono, and Singapore, to Thailand, Jordan, and South Korea, where he asked people to “trace” important objects—cellphones, fans, religious icons, even body parts of their companions.

Salvatus then “wrapped” these outlines in penciled-in, mummy-like bandages, to “preserve the imagination.” In another phase, Salvatus discovered photos on his uncle’s old laptop, taken during the elder man’s days as a globetrotting seaman, which he randomly arranged—an example of exploring family history to deliver a new, universal message of contrasts and perspectives.

Then, there was the time he dug up a photograph from the Lopez Museum of masked carnival revelers in Lucban from New Year’s Eve 1910, an attempt to start an annual event, which didn’t quite catch on. Over a century later, Salvatus would recreate the event, sending out a call for participants with posters, and photographing relatives and friends in homemade masks, which he later collected and stuck on a blow-up of the original 1910 photo for a museum exhibit.

The people of Mestre, our first stop, were up to the task of assemblage. I also ran into Rhea de Guzman, who displayed a Tupperware scooper as an “artifact.” Selling Tupperware was how her mother supported the family before they immigrated to Italy, and she had kept the scooper as a remembrance of her parent’s hard work and sacrifice. The “artifacts” were displayed on a wall as the “Museo de Mestre,” with individuals sharing what their pieces meant to them.

Next stop was Ferrara, capital of the northern province of the same name. We had a long talk with Amiel Masarap, president of the 300-strong Filipino Association in Ferrara, who has lived in Italy for 21 years but keeps very much in touch with his roots; he actually spent a year in the Philippines campaigning with the LGBTQIA+ community for Leni Robredo as president in 2022.

“We felt honored that someone from the Philippines came,” Masarap said. “In most of the communities here, the newer generations are starting to detach from Filipino culture. I think more occasions like this will deepen our connection with the Philippines.”

I met Emelita Maña, who displayed a rosary from Medjugorje, a gift from her late employer, whom she took care of for 11 years. Corazon Taganayon, a longtime domestic helper who now runs her employer’s household and staff, drew coconut trees in her home province of Batangas, where many Batangueños from Ferrara sent aid after the province was devastated by a typhoon.

And then there was Juliana Masarap, a relative of Amiel’s, who grew teary-eyed as she explained why she displayed a ticket from a ride in Innsbruck, Austria. She took a risk, she said, and entered Italy illegally 14 years ago, because life in the Philippines was difficult: “I had no hope there.” When she got her papers, she brought in her family, but unfortunately lost her husband to illness soon after. The Innsbruck trip was “the first time my four children and I traveled as a family after their father passed away. I’m happy because no matter what, we’re still together, and I’m able to take care of them.”

Mystical aspect

When we reached Naples, Italy’s third largest city, the turnout of members of the Philippine Catholic Community of Pedro Calungsod was small, but the stories they told blew us all away. Salvatus, being a street artist, loved the grittiness of the city; on one day, he actually watched a rally at the central Piazza Garibaldi. He also spoke of how growing up with Banahaw in the background made him feel protected by the mountain, a reference to the mystical aspect of its presence.

This segued smoothly into the sharing of the Filipino association’s president, Antonio “Jun” Tulauan Jr., who recounted a difficult childhood in his native Cagayan, and how he always found succor in Our Lady of Piat, whose icon he displayed in the “Museo de Napoli.” It was a story that left many almost in tears.

By contrast, Alice Martinez had the group in stitches with her account of her former life as a smuggler’s assistant (seriously), and how almost getting caught forced her to change her ways and start a new life in Italy, in spite of her rolling around in money. (“#Goals!” joked Quijon.) Her artifacts? Drawings of the credit cards under different names that she carried around!

Finally, more current memories were shared through the artworks of Charlotte Briones, an art student who had been born in Naples, who was accompanied by her mother Marilyn.

We spoke with the artist and curator in depth in the middle of the tour, with Quijon noting that the workshop and lecture series “is essentially a feedback thing. I like the way it’s been keeping me on my toes, and requiring me to adjust what aspects of the exhibition I need to foreground.” It was less a question of letting Filipinos open up and share than examining a not-so-obvious narrative: “It’s not always about belonging,” he said. “It could be how to think about or process feelings like, ‘I’m living a good life here, I don’t necessarily hate the Philippines—but I don’t want to go back’?”

People make assumptions about OFWs, Quijon said: They always miss home, are sad, or want to return. “The OFW can be a cosmopolitan figure, but we deny them that. What complex feelings do they have? The nation could be just one of the many things they’re thinking about.”

In Belluno, our next stop, our gorgeous location at the foot of the Italian Dolomites must have urged Quijon to bring nature into the discussion. “How do natural formations shape culture?” he asked, citing Salvatus’ 2017 and 2018 evolving installation “Museo ng Banahaw”—like the museos of the Filipino communities, not an actual place or structure, but in this case, an ever-changing assemblage of any cultural references the artist could find on the mountain. Thus, the “artifacts” evolved from mineral water bottles and cable TV materials, to old family photos and writings of Salvatus’ historian grandfather Ramon. Becoming an artist was a “natural development,” Salvatus said, because of his creative community.

Kind to immigrants

FilCom Belluno president Jun Isidro first came to this quiet town, in the province of the same name, in 1996, to train with several other Filipinos in a factory that produces bathroom ceramics, like sinks and water closets. The factory eventually hired them all, and the group became the first Filipinos to settle in Belluno almost 26 years ago. The people of Belluno are kind to immigrants, Isidro said; they never regretted relocating.

Richard Nuique was one of those Filipinos who joined Isidro; his wife arrived in 2005, his only child Denise in 2014. Nuique showed the access card he used at work, and the discount card he used at the neighborhood laundry, to represent his weekend “occupation,” he said with a laugh. Daughter Denise, now 29, confirmed that her dad took care of the laundry on weekends. Her contributions were a drawing of the wreath they crowned her with when she graduated from school, and a medal from Lourdes given by a friend.

Just as Ilocana Esther Barchet and I were speaking, her Italian husband, Evaristo, joined us to introduce himself—in fluent Filipino! They met in 1990, when she was babysitting for doctors and he was a music teacher. She has been in Belluno for 36 years; they’ve been married for 31, with two daughters now working away from home. “I fell in love with her because of her beautiful face,” said Evaristo, still in Filipino. Naturally, they proudly posted a family picture on the “Museo de Belluno” wall.

Finally, we ended the series in Udine in northeastern Italy, near the borders of Austria and Slovenia, with a high-profile, well-known Samahang Filipino sa Udine composed of some 500 members, and led by active female officers. President Mitchie Ijan, a widow (her late husband was Italian), has lived in Italy for 22 years, first coming to work in a home for the elderly.

Vice president Loida Salas, originally from Tacloban City, is similarly the widow of an Italian national, has lived in Udine for 30 years, and has two daughters who now work in different cities. It’s a very active Filipino association that celebrates Christmas, Independence Day, even the Sinulog and other festivals, events that inevitably include lechon, and yes, karaoke singing. Salas, a one-time professional dancer, leads a dance troupe that presents cultural performances, even for Filipino associations in other cities.

Also around was Floyed Ramirez, second vice president of the umbrella organization, the Association of Filipino Workers in Italy, which covers some eight provinces. Ramirez still works as a caregiver, but has brought practically their entire Batangas clan to Italy already. “We need a dedicated priest for the church, so we don’t always have to request for one!” Ramirez exclaimed, only half joking, when asked about their biggest concern.

The association members communicate online, and are particularly keen on assisting newly arrived kababayan with their papers. “We want to help Filipinos with their documents, or any other difficulties that might arise,” said Ijan.

Ramirez and Salas like to visit the old country, but now consider Udine home. “My two daughters are here,” said Salas, “and the quality of life is really good.” “I have a big house in Batangas, but my family is here,” added Ramirez with a laugh. “I have to use the money to pay bills!”

Wish granted

Salas shared her contribution featuring pictures of her two daughters, images of Padre Pio and the Virgin Mary, and a drawing of a lit candle. “My two girls are grown up, but my worries about them are still there,” she said. The candle represented her late husband, “whom I miss very much,” and the religious images accompany her wherever she goes.

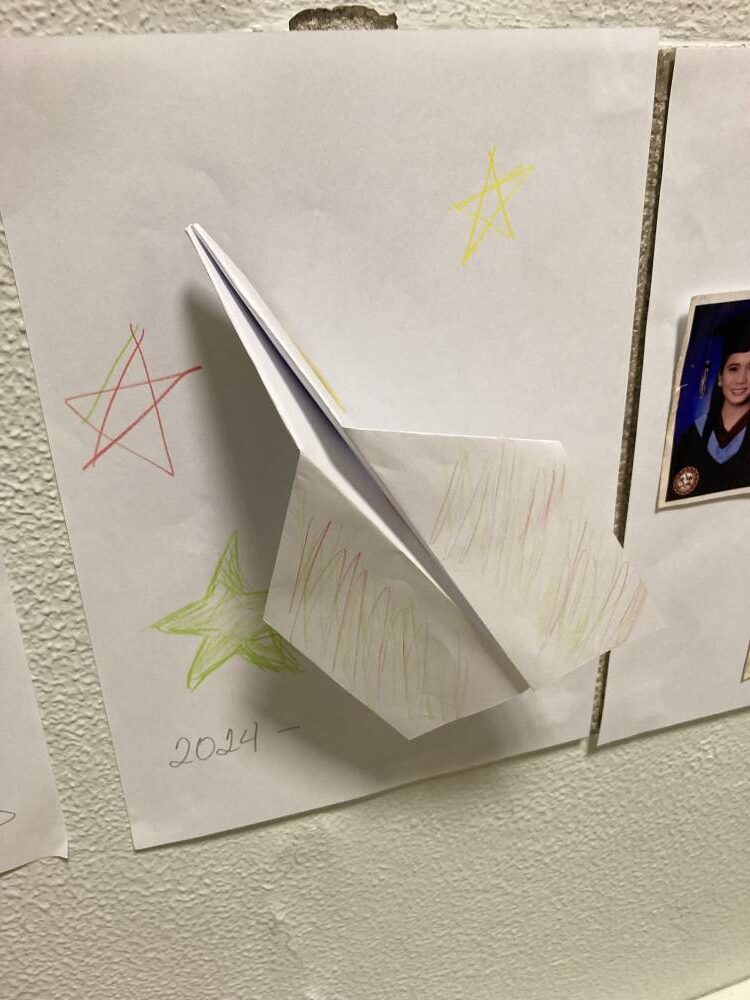

Karen Macatangay helped end our experiences on a warm note. She and her husband work as a couple in one household, and have lived in Udine for 30 years, but haven’t seen their two children in Manila since 2012. She creatively stuck a paper plane on a sheet of paper to put up on the wall. “It’s a wish granted,” she explained. As it turned out, her children were just given tourist visas, and as of this conversation, were set to arrive in Udine after Christmas for a two-week vacation—a much-anticipated family reunion.

“Part and parcel of our role is to ensure that we extend to several communities,” said PAVB Coordinating Committee head Riya Lopez of the entire effort, although this was not the first time they brought an exhibition to the people. “We had our initial contact, and then it grew and grew.”

A key facilitator, Lopez said, was Darwin Gutierrez, a.k.a. Kuya Darwin, former head of the Filipino Community of Venice Terraferma in Mestre and now an essential member of the PAVB team during exhibitions, even as he holds down a job as a hotel manager in Venice. Since some of the communities do not live very close to Venice, distance was a main consideration, Lopez noted, along with the perceived complexity of the artistic material. “That’s why it was important to level the discussion and explain the concept. You have to relate the concept, in layman’s terms, to these communities and their context of living. Like, ano ito sa buhay ninyo?”

The PAVB was there primarily as facilitator, Lopez concluded. The important thing was to share the story of the Philippine exhibition, and in turn, to get the Filipinos’ reactions and hear their own stories. “And our biggest reward is to be able to listen to those stories.”