‘Next to Normal’: Third time’s not always the charm

Some shows seem set up for success, armed with text that’s structurally airtight, emotionally rigorous, unyielding in its pursuit to deliver nothing but the most truthful moments onstage. All the production needs to do is, pardon the cliché, “trust the material.”

“Next to Normal,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning musical about a family fractured by its matriarch’s mental illness, easily qualifies as such a show.

Four characters form the crux of the musical: Diana, who struggles with bipolar disorder amidst the lingering trauma of her infant son’s death (no longer a spoiler at this point!); her husband Dan, stretched to his limits; her teenage daughter Natalie, also stretched to her limits; and Gabe, Diana and Dan’s son who, in a stroke of narrative brilliance, exists throughout the show in adult form.

Reviewing its 2009 Broadway premiere, Ben Brantley of The New York Times rightfully described the show as a “feel-everything musical”: one that exhumes “with operatic force” the deep-seated, familial anguish of its characters to become a frequently moving, occasionally devastating portrait of intergenerational dysfunction. And it also comes with an all-timer pop-rock score (by Tom Kitt and Brian Yorkey) that captures the jaggedness of its protagonists’ individual and collective psyches.

All that was evident in the first two instances this musical was staged in Manila: in 2011, directed by the late Bobby Garcia for Atlantis Productions, an “electrifying, heart-shredding” iteration that evinced complete “mastery of the Broadway musical idiom,” as I wrote in my best-of-the-2010s roundup for this paper; then, in 2020, directed by Missy Maramara for Ateneo Blue Repertory, a spare, emotionally lacerating, visibly text-first treatment—the musical “with its insides fully exposed,” as I described it. (The latter unfortunately closed after its opening weekend—one of 27 theatrical events forcibly shuttered by the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Lack of trust

Now comes Manila’s third glimpse of this musical, directed by Toff de Venecia for The Sandbox Collective. In brief, it only proves that third time’s not always the charm. What may seem a guaranteed win on paper can end up, like this production, a frigid and antiseptic experience.

Mirroring Diana’s fragmented mind, Sandbox’s “Next to Normal” alternates between gratuitous resorts to metaphor and a grating literal-mindedness that, taken together, betray a seeming lack of trust in the material—an uncalled-for itch to do “more.”

The reach for metaphors is apparent quite early. For example, the opening number, which introduces the viewer to the protagonists as they mill about the house getting ready for the day, culminates in the first hint that something’s awry in this otherwise ordinary household: In a manic frenzy, Diana starts making as many sandwiches as she can, “to get ahead on [everyone’s] lunches”—to the point of preparing them on the floor. This is made perfectly clear in the dialogue, as well as the script directions.

But in this Sandbox production, there are no sandwiches; Diana only sits, then stands, on a chair, singing her mania away. And while departures from the script are quite fine and routine in the theater these days, this specific instance is a head-scratcher, especially considering everything else that follows.

It might have made more sense if this impulse to leave things to the imagination were consistently the only feature here. But balancing this strange penchant for minimalism is an urge—just as recurrent, and no less bothersome—to spell things out in ways this production probably deems “expressionistic.”

There is, for one, a drawn-out, five-minute pre-show of sorts involving a Pablo Neruda quote being erased gradually on the wall, until only “absence is a house” (from the poet’s Sonnet XCIV) is left. Does this elevate the viewer’s understanding of the musical? Not at all, one realizes by curtain call, though the whole charade does add five extra minutes to the production.

Throughout, chairs become the centerpiece of movement: The actors carry around their own chairs, (re-)arranging them, emoting “into” them. It’s been 60 years since Dionne Warwick first crooned that “a chair is not a house/and a house is not a home …” Here, one is reminded of that song, to be fair, but this “Groundhog Day”-esque “chair choreography” is always far too busy, intrusive, and obvious to ever be truly meaningful. (In fact, the intrusive choreography doesn’t let up even in the final song.)

Emotionally static

Meanwhile, moments of intense emotion, as reflected in the music and lyrics, are often left emotionally static by the blocking and direction. When they’re not lugging chairs around, many times the actors are made to just stand there, or sit there, occupying their own spots, and sing to high heavens. The attempt to portray the characters in their closed-off, individual worlds is clear; the excess of unused space onstage is likewise painfully glaring.

Considering the amount of attention devoted to metaphors, to choreography (and nonmovement), to a lighting design that keeps calling attention to itself, it is a travesty that not much care has been given to the sound. While the venue—the Power Mac Blackbox Theater—is notorious for its appalling acoustics, this “Next to Normal” has to count as one of the worst-sounding productions ever staged there. The performances are thus wasted in this space; already made emotionally distant by De Venecia’s direction, they become literally incomprehensible because of the sound.

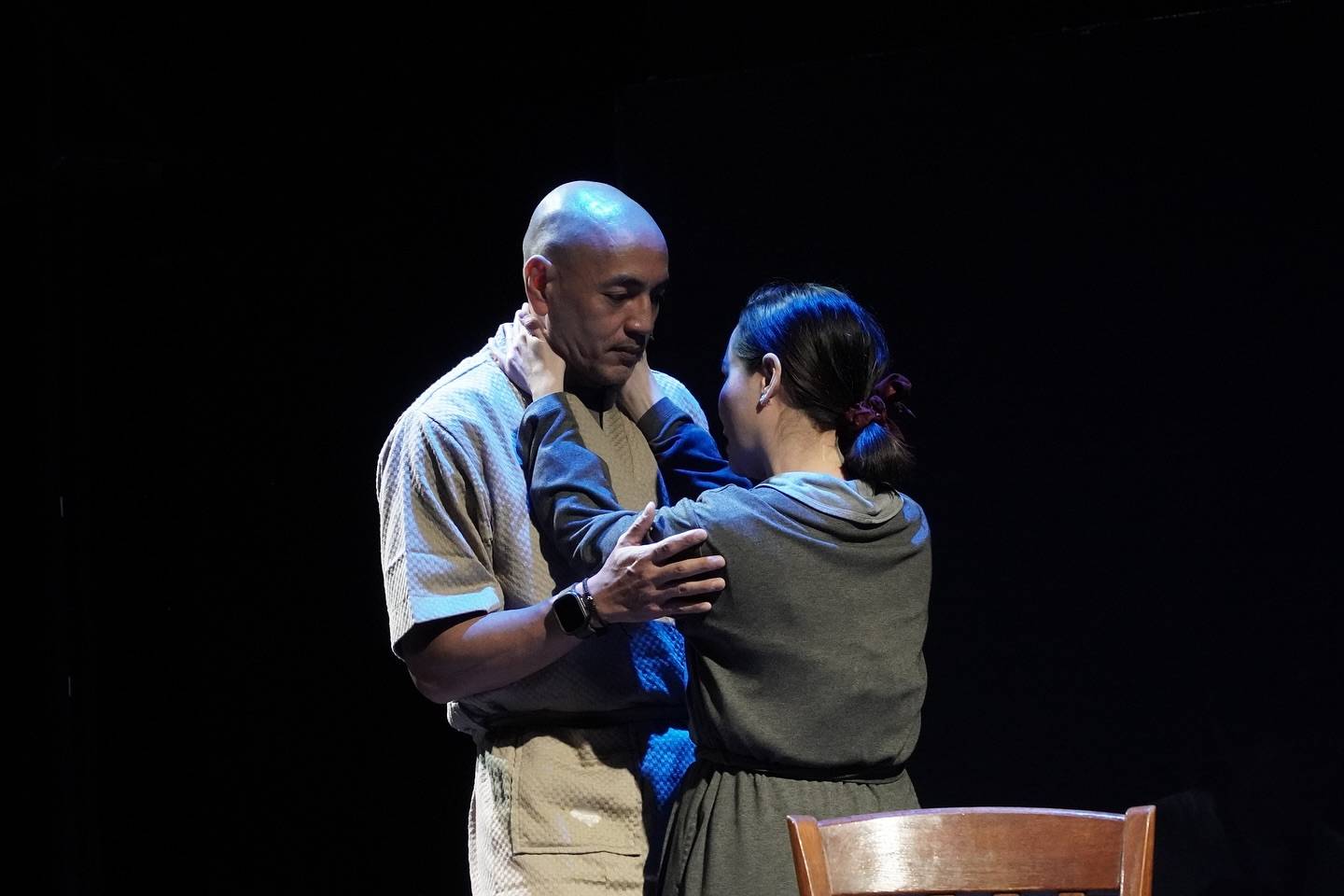

As Diana, Shiela Valderrama can be a vision of coherence in her best moments, while Nikki Valdez’s rawness occasionally works to her advantage (even if she’s frequently belabored by unsteady dramatic and vocal technique). Floyd Tena and OJ Mariano only manage to live up to the largeness of their characters in the second act.

Among the actors playing second-generation characters, Omar Uddin delivers the clearest performance by a mile; as Natalie’s boyfriend Henry, he not only lands what the character requires of him, but somehow enlarges the part through sheer will, his presence becoming the most compassionate and compelling in the show.

And if this production is about “making choices,” only Vino Mabalot succeeds in making an altogether interesting choice, his take on Gabe as a malevolent, teenage specter adding a much-welcome sprinkle of excitement to the proceedings.

Yet, Uddin and Mabalot (alternating with Davy Narciso and Benedix Ramos, respectively) are only pieces of the larger puzzle. The production they inhabit has neither the former’s flesh-and-blood accessibility nor the latter’s well-defined commitment to deviate from convention.

Like a number of Sandbox’s previous outings—last year’s “Tiny Beautiful Things,” the monologue “Every Brilliant Thing” and its Filipino translation “Bawat Bonggang Bagay”—this “Next to Normal” has been marketed heavily along the lines of mental health advocacy. And why not? The advocacy part is already crystal-clear in the powerful material. Rather than let the themes emerge naturally, however, this production ends up speaking over them—an exercise in muddying clarity.

“Next to Normal” runs until today, Feb. 23, at the Power Mac Center Spotlight Blackbox Theater, Ayala Malls Circuit, Makati City. Visit bit.ly/sandboxn2n for tickets.