Nicanor Tiongson’s ‘Collected Essays’: Indispensable guide to PH theater

There is no doubt that the works of Nicanor Tiongson have been indispensable for students, teachers and scholars of Philippine literary history, with profound and lasting effects. His arguments have been either eagerly embraced or critically challenged, but never ever discounted.

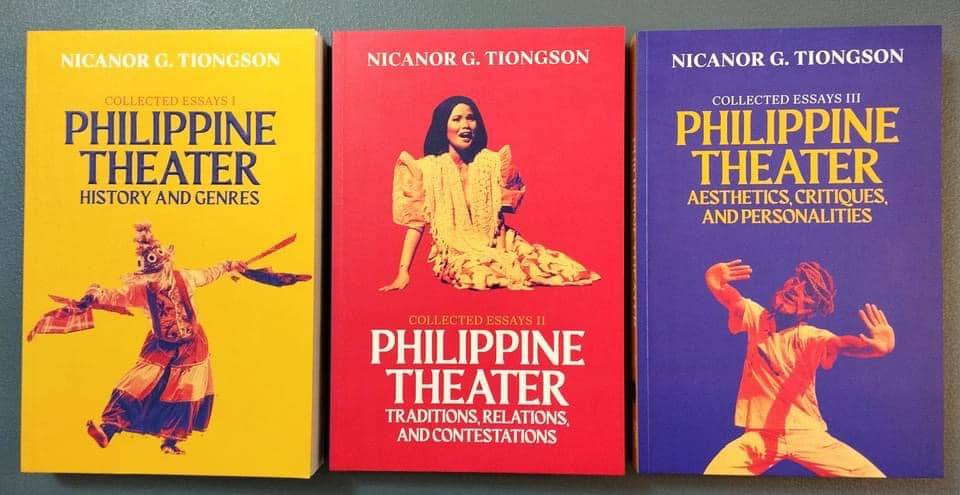

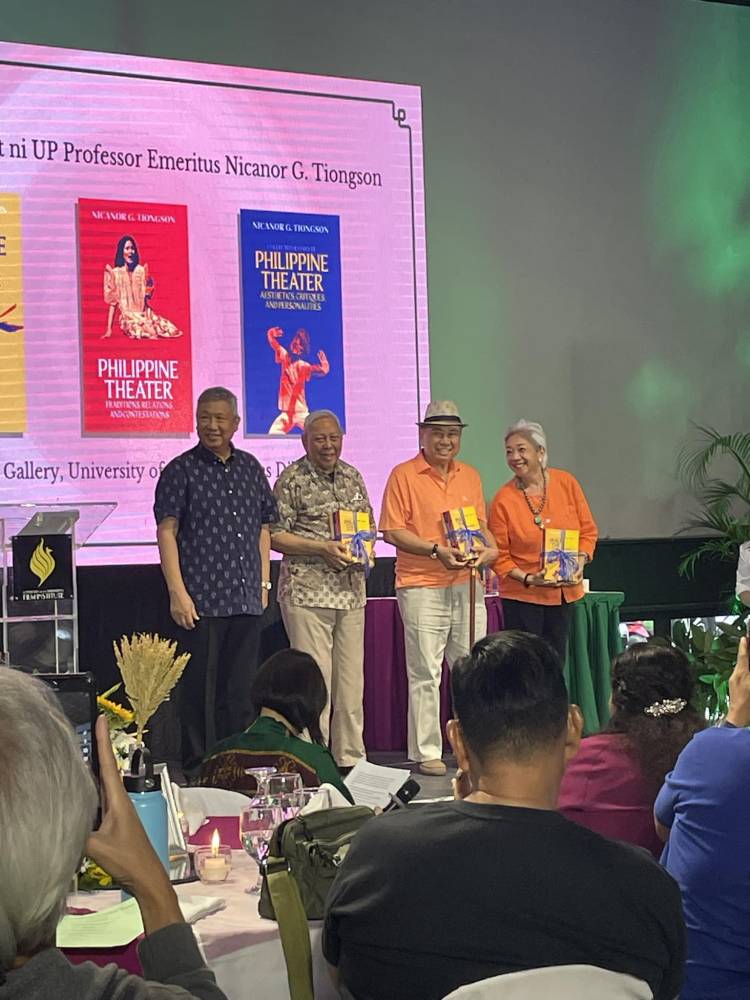

His “Collected Essays” in three volumes (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2024) gather his essays from 1969 to 2023; they are curated opportunely based on heuristic and pedagogical purposes for the modern readers.

One will benefit not only from the novel insights of Tiongson, but from the way he and his contemporaries approach the subject; such provides a glimpse of their intellectual lives and how they struggle to make sense of the perplexing issues of their time.

“Volume I: Philippine Theater History and Genres” focuses on the major genres of Philippine theater, arranged according to the historical period in which they first appeared in Philippine history. The last essay here—“The Contemporary Philippine Plays, 1986–1998: Defining Nation Through Theater?”—is about the plays written after the Edsa revolt and during the “decade of nationalism.”

It includes works on Philippine history, revitalized traditional plays, plays from the regions and from Metro Manila, all giving a glimpse of what shape the Filipino national theater would take.

Volume II is titled “Philippine Theater Traditions, Relations, and Contestations.” Under the section called “Tradition and Innovation” is the general essay, “Tradition and Innovation in Contemporary Philippine Theater”; it singles out specific contemporary plays that successfully innovated genres of the komedya, sinakulo, sarsuwela, panunuluyan and moriones.

Four approaches

Volume III is called “Philippine Theater Aesthetics, Critiques, and Personalities,” which has three sections. One of the essays included here is “Paano Nga Ba Manuod ng Dula?”—an essay written with professor Jerry Respeto that presents the four approaches that can be used in the analysis of Philippine plays: analysis of the artistic elements of the play and how they are orchestrated to express the theme of the performance; a discussion of the personal, social or cultural context that helped to shape the play; a description of the audience’s reception of the play; and an evaluation of the meaning of the play to contemporary audiences and its weight from the perspective of the “Kamalayang Pilipino na maka-TAO,” a consciousness that works for the full development of every Filipino as a person via protection and promotion of his human rights.

Over the past five decades, Tiongson’s writings as scholar and critic of Philippine theater have engaged with three major concerns: 1) the importance of the traditional forms in the creation of Philippine theater; 2) the search for a Filipino identity in theater; and 3) the politics of theater in Philippine society.

It is important to note that his understanding of these concerns has changed over the years in response to the turn of events—political, social, cultural—in Philippine society as well as his professional and personal growth in that society from the early 1970s to 2023.

For instance, his decolonization project started all the way back when he realized the dichotomy between rural lowland areas and the heavily urbanized centers in the Philippines, which leads to hierarchy and division among, on one hand, traditional theater composed of Hispanic genres like the komedya, sinakulo, sarsuwela, drama and the many short plays associated with Christmas and Lent, and, on the other, a modern theater consisting of either classic Western dramas or Western contemporary plays in English or Filipino translation, or original plays by Filipino theater artists influenced by European and American theater.

When the Americanized educational system integrated the study and even the staging of European and American classic and modern plays in the curriculum of the leading schools, Tiongson said that it largely ignored the traditional folk theater, thereby marginalizing and devaluing it in the eyes of most educated Filipinos.

Liberal values

But later studies made him realize that while it is true that bodabil became a major purveyor of American culture among the middle and lower classes, this variety show introduced a form of modernity into Philippine culture that conveyed liberal values and introduced a new concept of the woman who was economically independent of her partner, confident in her body and sexuality, and mistress of her own life and destiny.

This will prove, according to Tiongson, that Philippine theater, like all other forms of art in the Philippines and elsewhere in the world, is a mongrel theater, comprised of genres that were introduced from Spain and/or Mexico, such as the komedya, sinakulo, panunuluyan, pastores, moros y cristianos, sarsuwela and others, and from the US and Europe, such as realism, expressionism, epic theater and the musical.

This shows that Filipinos have adopted Spanish and other western forms for their own dramatic expression and for the formation of Filipino identity. Even before postcolonialism and cultural hybridism became the vogue among our scholars, Tiongson has already been doing field work and writing about these topics.

Crucial role

Finally, Tiongson believes in the crucial role of theater in Philippine society, and how it has played across the centuries—on the one hand, as a yoke for the subjugation of the people, and, on the other, as a sword for their liberation. He was heavily influenced by the Yenan talks, which led to his own reflexive estimation of the concept of “the masses.” He questioned the idealization and privileging of the working class to the exclusion of other classes, like the middle class, where ideological progressives could also be found. These questions only proved further the dialectical movement in Tiongson’s works.

Other victims of oppression should also not be lost sight of—women battered by patriarchy; LGBTQ+ stripped of rights by a homophobic church, state and even the movement itself; children victimized by domestic violence or sex trafficking; and the indigenous peoples driven out of their ancestral lands or eliminated by mining or logging companies of local and foreign capitalists close to government.

Hence, the theater embraces both the political and the personal that are intertwined in the dialectical and dialogical movement for emancipation. If only these essays could scream, one would definitely hear, “Let a hundred flowers bloom and a thousand schools of thought contend!”