Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz on the realities we should talk about more

What if you looked at your own life, your country, and the world—and said the things that no one else says out loud?

This is the prompt that simmers in the pages of “Imperfect Tense and Times,” Nicole Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz’s newly released collection of essays— published by the Vibal Foundation and edited by Charlie S. Veric.

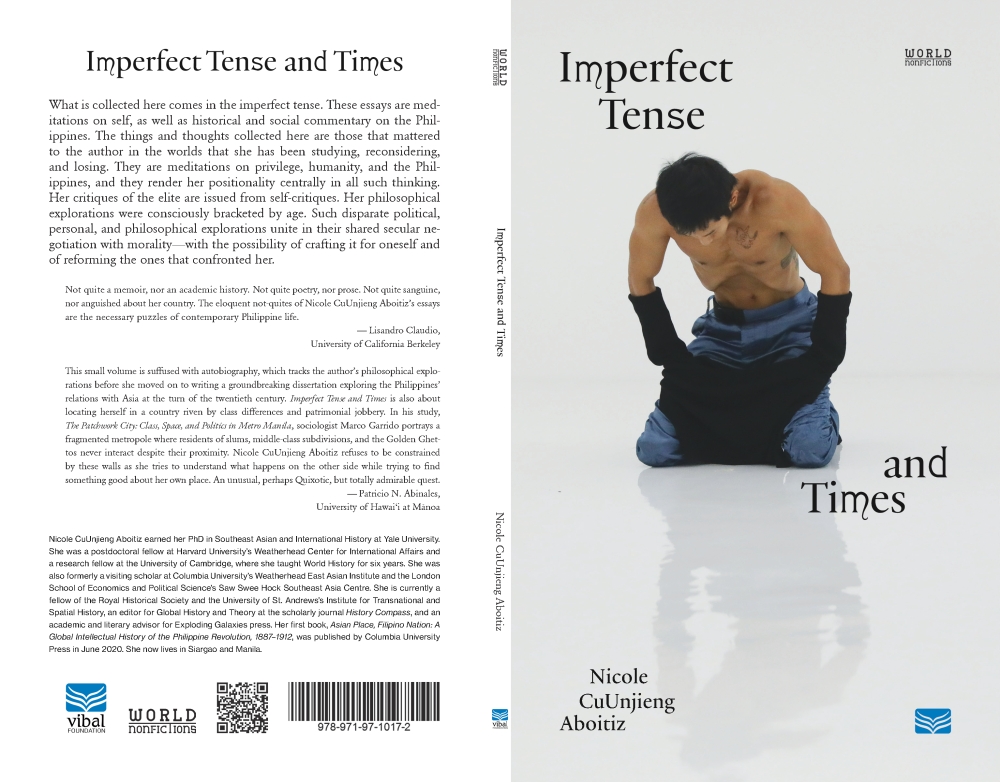

On its cover is a portrait of Mano Gonzales, photographed by Jacob Verzosa, with contributions by Derek Tumala. Inside are artworks of Gonzales, dividing chapters. “When I saw the photo of Mano Gonzales, I thought, ‘This is my chance to have ‘A Little Life’ cover—this is it!’” Aboitiz exclaims. “It was so arresting, so unusual, [and] so iconic.”

After the publication of her book, “Asian Place, Filipino Nation” in 2020, this collection of essays, titled “Imperfect Tense and Times,” collates her work from a decade ago—from when she contributed to The Manila Times over four years ago, while completing her PhD at Yale. The collection is a cerebral, yet emotionally open meditation on personal morality, as well as systems of privilege and power. Lucid and unflinching, Aboitiz explores the forces that shape both lives and nations, through memory, morality, inequality, religion, and the lingering shadows of empire. All with self-awareness, without self-illusion.

“I was surprised that this came to print in book form,” Aboitiz states. “What I had to offer was a critique of the elite from within—an imminent critique, a self-critique…one that would be more insightful because it came from someone who understands the codes of the elite as a native member of that class.”

Her self-awareness is sharp, candid, and hard-won. When we spoke, she had just arrived in Manila from Siargao—where she now spends half her time living, surfing on a regular, and raising her family. But in another life, she accomplished academic appointments at some of the world’s most respected institutions: a research fellow at the University of Cambridge, supervising in World History; a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University; and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics.

And it shows.

In an era where nearly half of writing on the internet is AI-generated, Aboitiz’s thinking feels rare. The essays made me feel like a student again—curious enough to look up her references, from Victor Frankl to quotes from poetry or magazine journals, and little-known events under German romanticism.

Among the reviews, Lisandro Claudio described the book as, “Not quite a memoir, nor an academic history. Not quite poetry, nor prose,” further adding that the essays are “necessary puzzles of contemporary Philippine life.”

Splendor in the grass, glory in the flower

The book opens up with personal essays that are a little punk rock, with a tinge of nostalgia and subversive edge. “Undercover Undergrad” starts with an experience many know: the creeping feeling of getting older. Aboitiz, then a graduate student, writes her response to a friend’s invitation to “throw an epic dance party…like we used to,” while recalling undergrad memories of watching The Knife in a concert, homemade raves in a college basement, and living near friends in a one-mile radius. But then she quotes Wordsworth, aware of how it is painfully true that, “Nothing can bring back the hour—of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower.”

But on that night, as an undercover undergrad, she felt it again. And in her other essays, she explores religion, literature, and imagines the undercurrents of lives unlived.

“I was surprised at how much religion came up in the essays…New Age, Buddism, Taoism, Jesus, our Folk Catholicism,” Aboitiz reflects. “And yet religion currently occupies no space in my current life. It was clearly a reflection of that in-between phase of being young and being old—a time capsule of that moment.”

“I don’t question things with the same regularity anymore. Back then, I had urgent philosophical anxieties. Now, they’ve become physiological,” she says in a thoughtful tone.

Uncomfortable truths

From the intimate, the book expands outwards—moving into social and political critique, while turning her gaze on Philippine politics, social hierarchy, and the cost of our national myths. Through her written word, she dismantles the many problematic structures that motivate the larger population, but does so in a way that is unperformative—learned, but not showy. Politically engaged, but not waving slogans.

For example, Aboitiz dissects Janet Lim-Napoles’ affidavit on the P10 billion pork barrel scam in 2014 with a refreshingly incisive lens. She recounts reading the statement voraciously, as if a tabloid, citing how its “detailed realism and veracity of the world of prosaic corruption…provide us with the darkest lived satire indeed.” She self-critiques the “neoliberal nightmare” of going to international schools, and in effect, “the consolidation of the Philippine elite,” because let’s face it—we all see it. We’re all very aware. In a particularly touching essay, she dedicates reflections to her yaya and the Philippine OFWs, recounting the steady dawning of the immense, often invisible sacrifices they make, with awareness of the unfairness privilege serves on a plate.

“I shared the essay I wrote about my yaya with my yaya,” Aboitiz says. “But I had no delusions that I was writing for a class other than the one I belonged to…The only person I knew reading them was my dad…But I think I was also writing for the proverbial Tita of Manila—someone quite comfortable who has not been forced to think through questions about class.”

Among the essays, she reflects on natural disaster and systemic inequality in “Do Not Say That ‘The Filipino Spirit is Waterproof,” calling out the government for its irresponsibility, with the hope that the column could inspire feelings that enact change—if our government leaders could be so inclined to read such things.

Nuanced takes on history

As a trained historian, Aboitiz has nuanced, different takes on history and often countercultural perspectives—unafraid to interrogate our more dominant narratives, which are too often accepted without question.

“It made me see the structure of Philippine oligarchy in a longer temporal frame,” she says. “I think I’m more separated from some of the discourse around me because of the historical training I’ve had.”

She raises interesting points, like why did imperialism rise in Europe and not in Asia? She explores religion—specifically Catholicism in the Philippines—and critiques on race and identity. Some of her unique cultural analyses include articles like, “The King and I: A Musical Lesson in American Cold War Ideology,” along with a reflection on the time when majority of Filipino audiences praised the release of the film “Heneral Luna” in 2015, in which Aboitiz dared to criticize the portrayal of black-and-white categorical moral positions and absolute, simplistic vilification of the West.

A voice of clarity, not comfort

With a deep historical consciousness, backed by a strong personal ethic, Aboitiz writes as both witness and participant in the ongoing work of understanding past and present.

Like its title, “Imperfect Tense and Times,” Aboitiz gives a grammar refresher—reminding that the imperfect tense describes “something repeated in the past, something that used to happen…It was of note. It had impact.”

But her essays go beyond grammar to gesture at something larger—that is, using the imperfect tense as a lens to study unfinished conversations, while raising issues that still remain unresolved.

Bravely, she admits that, “Just because I was aware [of inequality], maybe that allowed me to continue my relationship with poverty and inequality. And still feel better without actually being better. I was thinking about inequality and class differences, but I wasn’t actually enacting any change in my life.”

Aboitiz does not pretend to be above the systems she critiques, and shockingly, she indicts herself first.

Highly aware of her positionality and privilege, she says, “Unfortunately, a lot of the traditional carriers of national history are elite-dominated. But our big responsibility now is to historical truth. There are many interpretations, but some things definitively happened, and some did not. History isn’t just gossip. There are body counts, evidence…We have to uphold a baseline of truth.”

As she studies systemic forces and dissects the contradictions of privilege and morality, Aboitiz’s writing challenges readers—now asking them the question: What happens when you recognize the chasm between your ideals and the life you live?

Without drawing a neat conclusion, Aboitiz makes the personal political—compelling readers to reflect, reckon, and raise harder questions (without having to have all the answers). And perhaps in doing so, creates a kind of resistance, especially necessary in these imperfect times.

“Imperfect Tense and Times” by Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz is now available through Vibal Foundation’s World Nonfictions imprint.