‘One Battle After Another’ mirrors America’s age of paranoia

They always say, art imitates life, right? Paul Thomas Anderson has always been a filmmaker attuned to the psychic weather of America. From the ruthless ambition of the Western thriller “There Will Be Blood” (2007) to the psychological period drama “Phantom Thread” (2017), and even in a sense, the absurdism in the strange romantic comedy “Punch-Drunk Love” (2002), his films look at personal obsession within our much larger systems of power.

Anderson has taken from the novels of Thomas Pynchon before, such as “Inherent Vice” in 2014. Now, he loosely adapts Pynchon’s ominous voice in the 1990 novel “Vineland” to “One Battle After Another,” a recent winner of four Golden Globes at the 2026 awards show. While loosely adapted and taking considerable liberties with its source material, the result is an action thriller that doubles as political satire, unfolding in a heightened reality that doesn’t feel far removed from our own.

You say you want a revolution

Well, these characters want to change the world. Running nearly two hours and 40 minutes, the film oscillates between fast-moving, kinetic spectacle and intimate, sometimes disturbing, psychological tension.

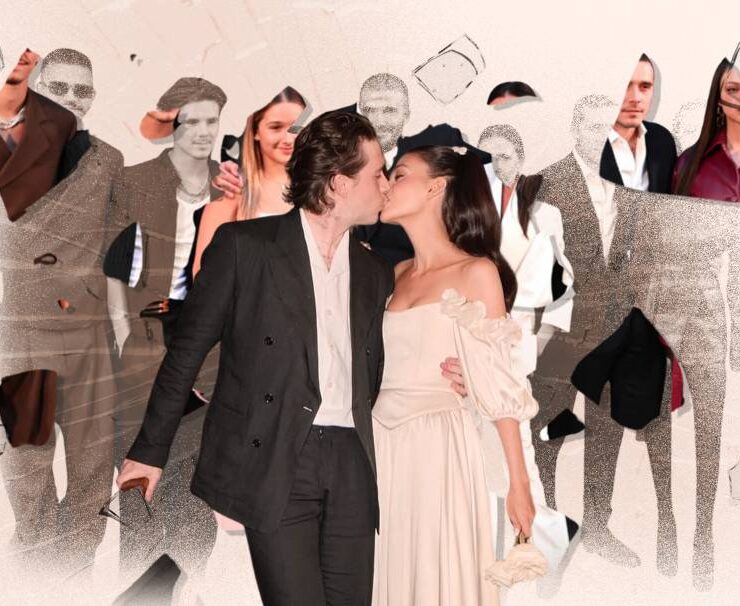

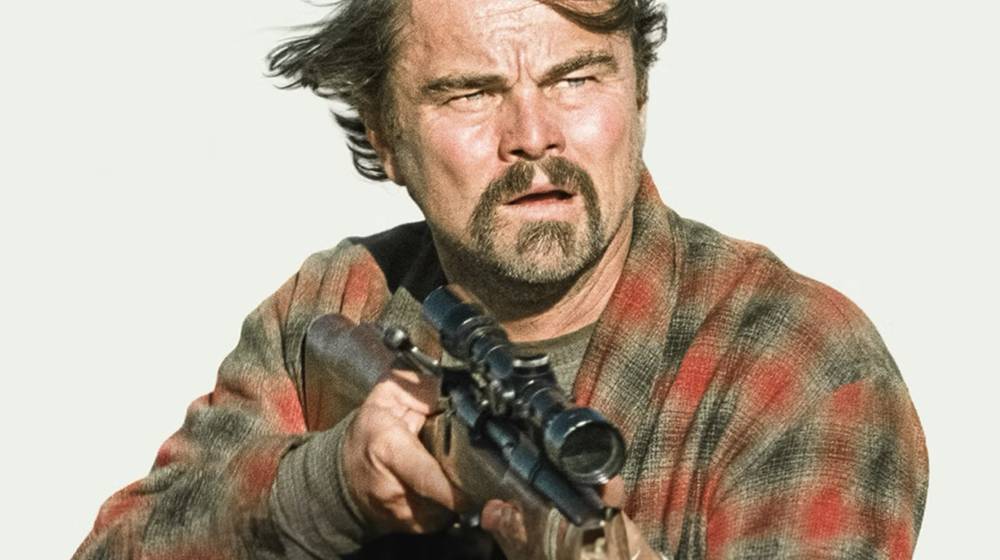

It starts with a somewhat oversexualized romance between Leonardo DiCaprio’s character Pat Calhoun (later renamed Bob for safety), an explosives specialist, and a reluctant, constantly stoned revolutionary involved with the French 75. Benicio del Toro also has a standout performance, playing a Taekwondo teacher aiding in an underground network helping immigration cases of Mexicans.

The French 75 is a loosely organized insurgent group whose lineage recalls the radical (and undoubtedly, super-cool) movements of the ’60s and ’70s, like the Black Panthers. Alongside him is romantic partner Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), a feral, magnetic presence whose “jungle woman” energy resists domestication.

The French 75 funds its operations by robbing banks, redirecting that firepower toward liberating immigration detention centers along the US-Mexico border. These sequences of children separated from parents, and the US armed raids are executed with chilling efficiency, which are not treated as shock tactics but as normalized operations. The degree of military involvement shows how casually it expands into civilian spaces.

Anderson stages this violence with technical mastery. The pacing is assured, with controlled performances. The action sequences, particularly the car chases, are among the most hypnotic of scenes. The film’s final procession of three cars gliding through rolling hills plays like a waking dream, an eerie lull after sustained chaos.

Power, masculinity, and the cult of authority

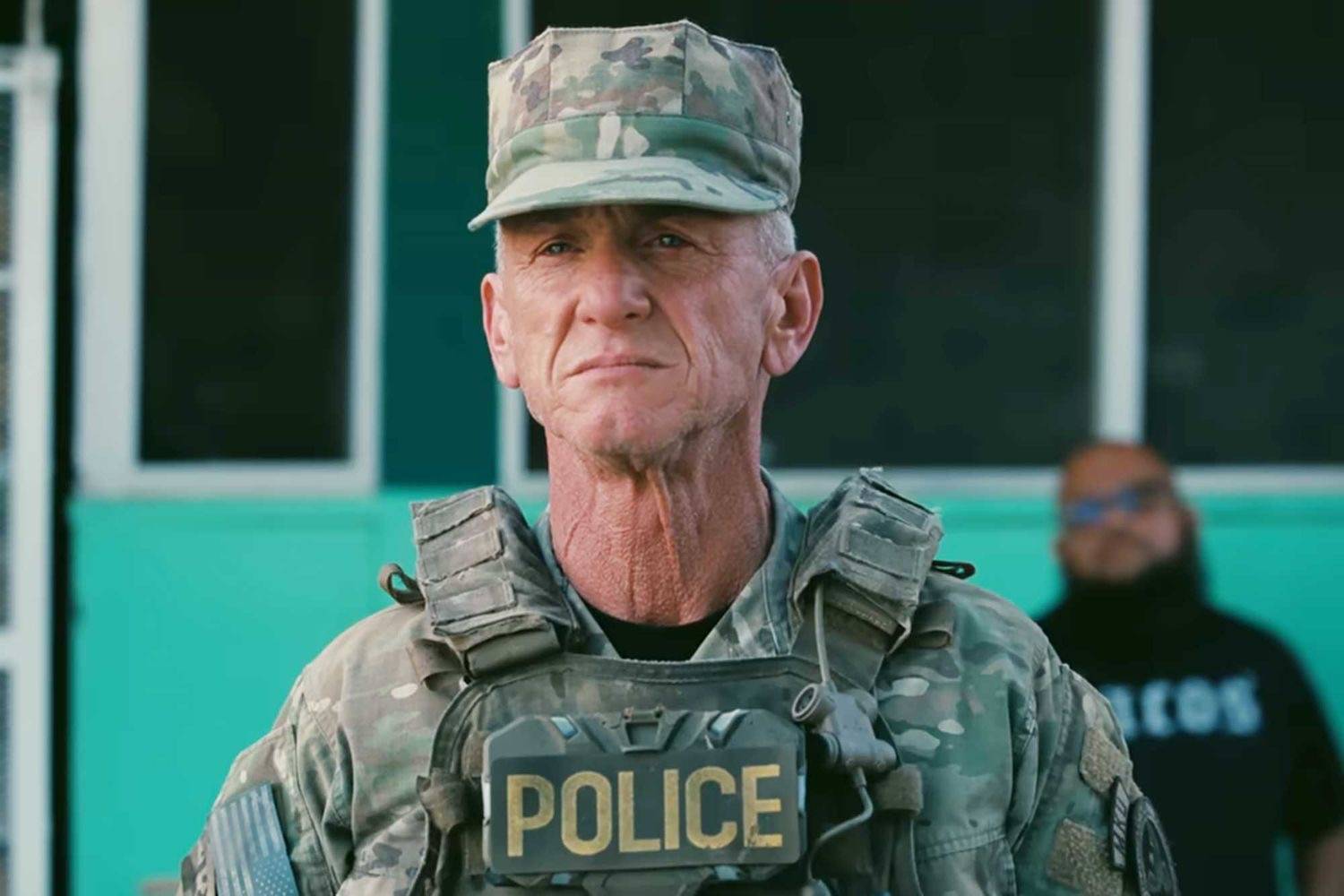

Chasing the French 75 is Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw, played with grotesque relish by Sean Penn. Lockjaw is a corrupt military officer, a representation of institutional masculinity whose cruelty feels cartoonish. He runs the US-Mexico border and, despite his overt racism against immigrants, develops a freakish obsession with the black Perfidia.

Later on in the film, he has become a man who is desperate to be taken seriously. Lockjaw becomes the ideal instrument for the film’s shadowy elite: the Christmas Adventurers Club—a wealthy, secretive cabal of aging white men. They hint at the US’ ruling class, often deeply insecure, sexually perverse clowns (Jeffrey Epstein and co. come to mind?) who ruin lives with their power and through their wealth.

If Lockjaw feels exaggerated, it’s only because reality has caught up. The film’s depiction of violent military counterinsurgency that spills casually into civilian life feels unsettlingly plausible, and of course, brings to mind the senseless raids of the US’s ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). Scenes feel familiar with overexaggerated military men, waving around their guns, and raging in full gear. They carry around battering rams, which seem to be the favorite tool of ICE in their raids.

Anyone who finds this implausible, the film seems to suggest, hasn’t been paying attention to the headlines.

Children and borders in between

At the film’s emotional core is Willa—formerly Charlene—the daughter of Pat/Bob and Perfidia, renamed repeatedly for her own protection. Her existence sparks a deadly rivalry between Pat and Lockjaw.

Willa is also where Anderson grounds the film’s politics in lived experience. A throwaway line about Bob not knowing how to care for his daughter’s kinky hair reflects the director’s own life. Anderson, who is married to a Black woman and has mixed-race children, has spoken openly about navigating this exact anxiety.

The film shows little mercy when it comes to children, as they are detained and displaced with bureaucratic indifference. If anything, the movie pulls its punches. Recent real-world cases of women and children endangered during ICE operations also reveal a system even more lawless than Anderson’s fictionalized version.

And while the film might feel “pro-illegal immigration,” it really reflects a deeper reality. America has long exercised discretion in granting people the grace to stay when returning to their own country would be too dangerous, but President Donald Trump has removed this grace, as the US is no longer the “Land of the Free.”

It’s worth noting that “One Battle After Another” also has a quirky sense of humor, which feels apt, as lately, late-night shows and comedians seem to be one of the most active voices in criticizing ICE raids.

A mirror of satire and spectacle

Critics have noted the politics, too. NPR’s Justin Chang called the film “prescient and political,” while Michelle Goldberg in the New York Times described it as an artistic antidote to fascism.

The film is clearly well-made, with good acting, well-done pacing, and top-notch action sequences. Through these, the film captures the atmosphere of America today, with paranoia from violent shootings, the expansion of armed authority, and violence as dangerously normalized, and something to be wary of every day.

Looking at the title, “One Battle After Another” seems to suggest a struggle without resolution. The film does not totally diagnose American politics either, and instead delves more into the intimate power struggles of the characters themselves.

So see it for the craft, the performances, and the sensational action sequences. But leave room for the unease it plants. While Anderson’s film may exaggerate, it reflects a country where fear has become built into the infrastructure, and the line between satire and real news reportage grows thinner by the day.