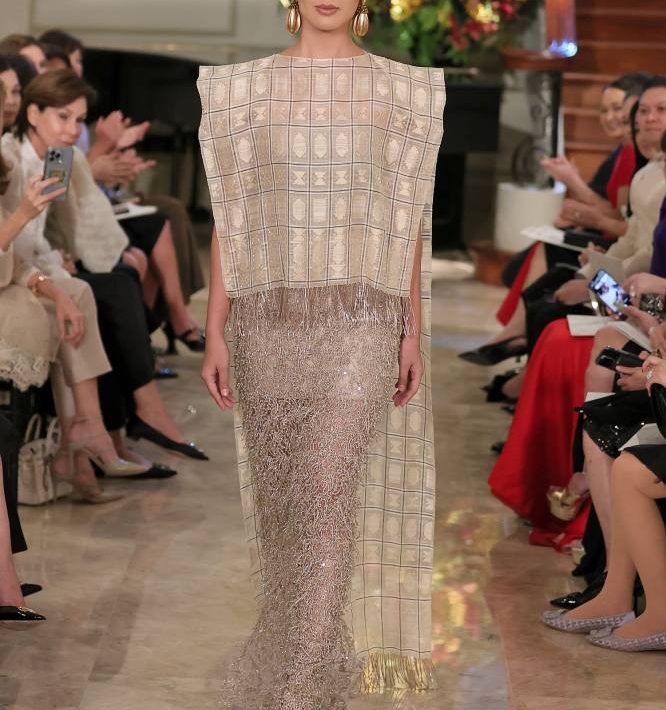

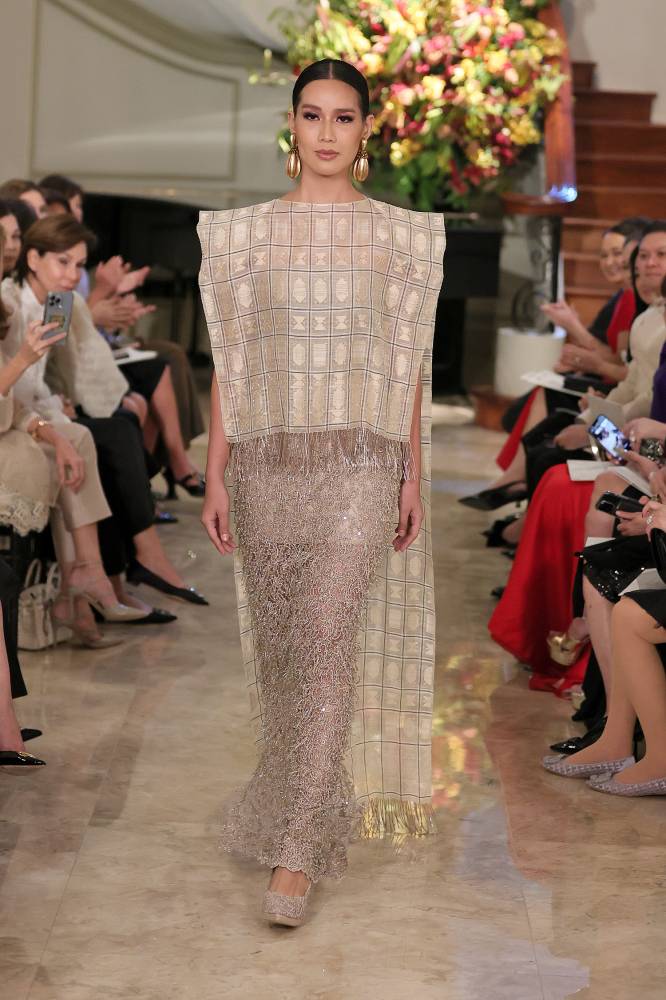

Paul Cabral’s fresh proportions—and new possibilities for piña

+41

+41 Paul Cabral’s fresh proportions—and new possibilities for piña

Piña was on the verge of becoming a dying tradition, as pineapple farmers and weavers were desperate for a market. But when designer du jour Paul Cabral held his first-ever fashion show, he showed exciting possibilities for piña by creating styles with modern proportions; mixing it with other luxury fabrics; customizing it in stripes, checks and natural dyes; infusing various embroidery techniques, and layering it with other textures.His show likewise celebrated the launch of the newly renovated Laperal Mansion, the presidential guesthouse for visiting dignitaries on Arlegui Street, Manila.

Many designers have thrived by capitalizing on hype or theatrics at the expense of workmanship. Cabral has been lauded by fellow designers for his crisp tailoring, understanding of how fabrics move with the body, seamless construction and proportion. These are why he has been the choice of the crème dela crème. Paunches disappear in his barong for men while matrons appear taller and trimmer in his evening wear.

“You can’t fix their bodies. But if the clothes have lumps and bumps, they look fat. If the fitting is smooth, they look slender. That has been my training,” he told Lifestyle.

Joe Salazar’s ‘Anointed One’

Cabral began as an assistant to the late celebrity makeup artist and designer Fanny Serrano and to couturier Aureo Alonzo. Under the tutelage of Joe Salazar, he picked up his mentor’s style—the use of soft luxurious lining to make gowns look voluminous but light, dainty embroidery and layering.

“Mag-mukhang mabango (It should look fresh),” he said. With his uncompromising standards and attention to minute details, Cabral became Salazar’s Anointed One. Salazar’s master cutter gifted him with the late couturier’s fabrics that were used in the collection.

The designer also nixed the rumor that he outsourced the sewing to other providers. “You can’t separate the office from the atelier. When the client comes for a fitting, the cutter and sewer must be in front of them to see how the outfit falls on them. They can look into the cause of the problem if there are any,” he explained.

Cabral added that if the suppliers were highly skilled, they would have gone on their own or worked full time for a designer.

Deceptively simple

His designs looked deceptively simple. It would take a trained eye to see the challenges in cutting and sewing the fabric.

The show began with a beige Italian Mikado silk dress, embellished with repetitive floral cutouts. It had the same silk lining as the dress—as Salazar had taught him. Cabral said the challenges were in hiding the seams and making the perfect cutaway hemline that curved to the back and moved as if it were windblown.

Another tour de force, a red silk terno with bouffant layers, was made with intricately shaped butterfly sleeves with folds that flowed into the torso. Like the beginning, the finale was understated but detailed—a fully beaded Maria Clara top with a well-constructed skirt.

Then there were fun separates created with open weave fabric, similar to solihiya.

The crux of the collection, piña and jusi, was Cabral’s support for first lady Liza Marcos’ advocacy of preserving local weaving. He explained that a designer needs to combine piña with other fabrics to update the look.

The all-beige collection featured jusi, a blend of local silk and vegetable fibers with calado or lace-like and mesh patterns, and bordado, ornamental embroidery, all made in Lumban, Laguna.

The men’s collection looked youthful with loose tunic tops with dropped sleeves paired with embroidered jusi city shorts. Cabral played with embellished bibs and vests as accents for shirts. One had to look at fine details such as a beaded bib on the front of the piña shirt and fine hand-pleating of the back for ease of movement.

The sinuksok, an embroidery method of inserting colored threads to make patterns, was interpreted as a colorful trim that added contrast to a beige piña shirt. A black barong with rosettes was designed for the metrosexual and the young at heart.

Customized stripes in various lengths, widths and spacing enlivened piña fabrics that were used for tops and bottoms.

Fabric manipulations Cabral’s version of layering was combining several separates in different embroideries. An embroidered mesh top was teamed with a piña vest with lace appliqués and a sinuksok skirt over a vintage lace petticoat.

For those who want the shine without being too loud, there were the handwoven silk gown from India adorned with dangling pearls and the Italian brocade skirt complemented the fully beaded piña calado top.

He was proud of the pleated piña that could pass for the famous Issey Miyake pleats. “Piña is super delicate. The more you handle it, the more fragile it becomes,” he said. How he pulled off the crispy pleats was a trade secret.

“They say wearing something in pure piña tends to look dated or boring. But it becomes exciting when you mix it with different fabrics and looks,” said Cabral, who bravely mixed striped piña with lace.

The designer pointed out that all the 73 styles in his collection were matched with customized footwear—Zarah Juan and Marikina shoemakers for the men and Doreen Odvina for the women.

All told, Cabral capitalized on quality fabrics with the knowledge that the material was the foundation of the design. He waited for six months for the pineapple fabric to be completed in Aklan and four months for the embroidery designs from Laguna.

“Calado embroidery is expensive, but you need to invest to achieve a collection that is unique, young and contemporary. It’s also important to know how to cut and sew,” he said.