‘Prince of Dance’ Nonoy Froilan nominated for National Artist

The local government unit of Calbiga, Samar, has nominated danseur, dance coach and ballet mentor Nonoy Froilan as National Artist for Dance. Also a Gawad CCP awardee in the arts, Froilan recalled the only life he knew—dancing, teaching, coaching for more than 30 years.

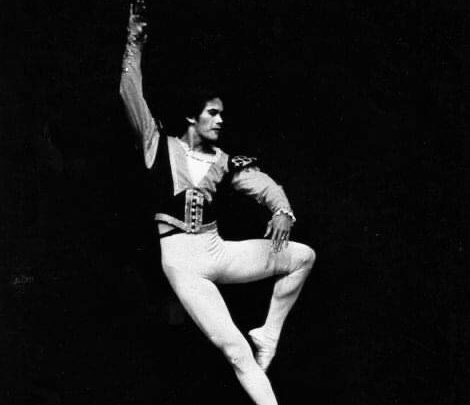

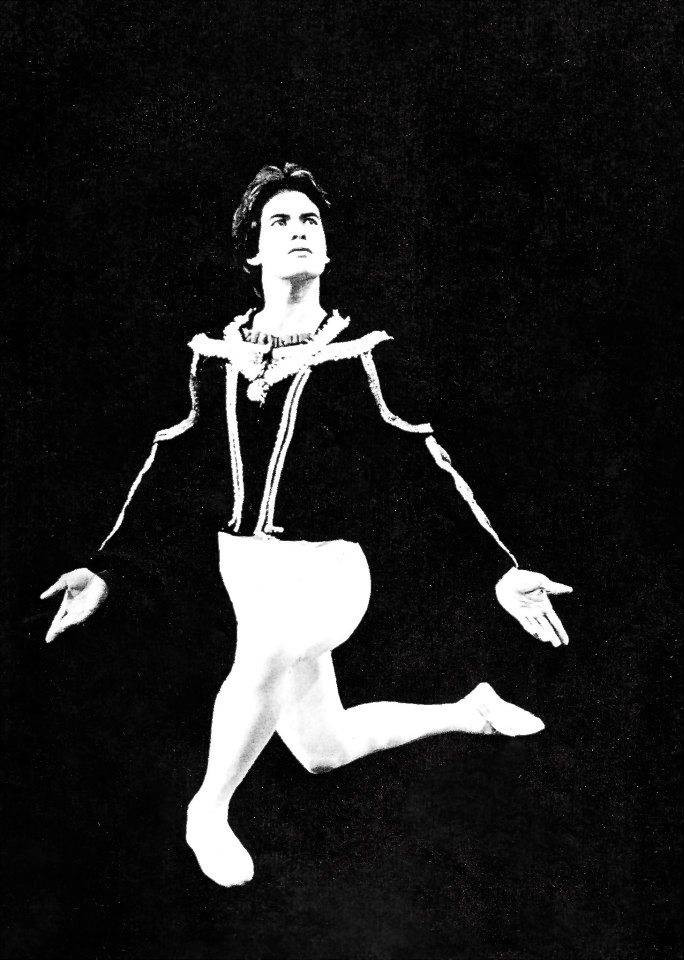

He was Siegfred in “Swan Lake,” Albrecht in “Giselle,” the voyager in Norman Walker’s “Season of Flight,” among other roles.

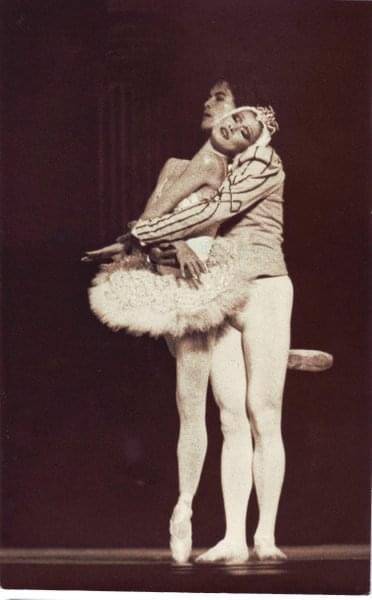

He has partnered the revered prima ballerinas of dance, namely, England’s Dame Margot Fonteyn, Japan’s Yoko Morishita and our very own Maniya Barredo.

Most unforgettable in his dance memory was dancing with Dame Fonteyn in the early ’70s. The ballet was “Dahil Sa ’Yo” by Mike Velarde, and Dame Fonteyn had John Meehan and Kelvin Coe (principal dancers of the Australian Ballet) and Froilan as codancers.

He recalls the first encounters in the rehearsal hall. “They were gods walking into the room and I can’t believe they were dancing with me. I let out a silent shriek of admiration while my heart palpitated in excitement. When you are dancing and partnering a prima ballerina assoluta like Dame Margot, you have to show your best. Dancing side by side with her … was no ordinary encounter. I felt I had to do my best as I was dancing not for personal gratification but more for your country … I recited a mantra while rehearsing, ‘I must blend with them.’ They were the living icons in the midst of us mere mortals on that CCP (Cultural Center of the Philippines) stage. Quite nervous, I wished I was just back in the wings watching them instead of dancing with them. But for some reason I always got the leading roles, which meant bigger responsibilities.”

The role of Albrecht in “Giselle” with Morishita was a turning point. “Dancing with her gave me renewed inspiration to excel. She was exquisite, humble and light. And she kept on coming back to Manila to dance with me.”

Favorite roles

One of his favorite roles was in Norman Walker’s “Songs of a Wayfarer.” Although it was based on a poem by Gustav Mahler, he knew it had something to do with the choreographer’s personal life. “I think it was one of my biggest breaks and the most terrifying,” he says. “Norman was always screaming during the rehearsal, trying to perfect his work.”

Many times, after retirement in 1993, Froilan was asked to restage classical works he has danced before. “The challenge with most classical ballets is the audience is already expecting the 32 fouettés or the series of tours en l’air. A dancer just has to do it. Once, I asked permission from Georgian Vakhtang Chabukiani in his restaging of ‘La Bayadere’ if I could change a pirouette because I was not good at it.”

It’s always de rigueur to ask permission to change choreography, whether the creators are still alive or dead.

“Interpretations are expected to evolve, but I still believe in sticking to the original choreography for it to become a true classic. It’s because I worked with the choreographers first-hand and I want to transfer everything I heard from their mouths—their voice, style, technique, their doubts, their creativity that made the dance brilliant.

“I become a bit stricter with contemporary interpretations because of their particular style and technique which are harder to learn. Some dancers can easily adapt to a certain style even if they are classically trained. But the rudimentary method between technique in classical and contemporary dance is being weightless in the former and grounded in the latter. I always approach a dance given to me with a model in my mind.

“The late Manny Molina … I tried to dance like him because his movements emanated from the mind of the choreographer. I definitely will not be a Manny Molina or dance like him, but the fact is, the image inside my brain manifests into the dance. Mikhail Baryshnikov is one of my favorite models in classical ballet. I will watch his variation three times before leaving for CCP with the mantra, ‘I dance like Baryshnikov.’ I always aim for his perfection even if I know I can never dance like him.”

20-plus years of dancing

He recalled bowing out of the dance scene and was suddenly face-to-face with a final dance tribute.The mere thought of retirement was unnerving. The urge to fade out of the dance scene came as early as the mid-’80s, but every time Barredo or someone like Morishita was in town, the surge of excitement swept the retirement plans away. He just couldn’t give it up.

In more than 20 years of active dancing, his world revolved around the theater—the daily workout with or without performance since he had to be in top shape for world premieres. He had to continue a performance even in the middle of an injury. He was in the theater during floods, typhoons, coup d’état, rallies and yes, even during earthquakes and volcano eruptions.

The only time he was taken away from the daily dance routine was when he took a bride (Edna Vida, the dancer and choreographer) and fussed over his now grown-up daughter and son Micaela and Rafael Jr. Fatherhood gave him a role different from those he played onstage.

In the gallery of Filipino male dancers, he inherited the throne left by Eddie Elejar, essaying nobility which contrasted with the passion of Enrico Labayen, the cerebral appeal of Rey Dizon, the fire of Molina and the virtuosity of Nicolas Pacaña.

Indeed, for more than two decades, he was the country’s Prince of Dance, carrying the torch for the country’s male dancers.

From Calbiga to Manila

Now 73, Nonoy Froilan was born in Calbiga, Samar, and didn’t have dance in mind for a career. His simple folks wanted him to study as a seaman in Cebu, and was later advised to apply in the US Navy.

He recalled: “My Samar high school days were very eventful. What I remember was that I often figured in school programs, where I learned Russian and Spanish dances. Later I was even nominated dancer of the year. I was also part of a singing trio.”

A summer vacation in Manila changed all the family plans for him. His idyllic Calbiga nights turned into neon lights in the big city. At the time, he was dark-skinned, the color of a burnt kettle.

In the late ’60s, he enrolled at the University of the East with no specific course in mind. “I just wanted to earn a degree and get a job. Then I saw an announcement in ‘The Dawn,’ the school paper, for students who wanted to join the school dance troupe.”

He passed the audition.

The dance troupe opened many doors for him. In time, he learned folk dance, jazz and basic ballet. “I learned how to quickly change from one costume to another. “

In time, with no dance roles beckoning, he was one of the backup dancers in the TV specials of Vilma Santos, Edgar Mortiz, Tirso Cruz and Nora Aunor.

The serious training in ballet and jazz soon began with him getting a scholarship under Julie Borromeo’s Dance Art Studio, where he had a very good mentor named Tony Llacer. “He gave me a good foundation for my initial ballet training.”

Slowly he was ushered into the world of show business, theater musicals and even fashion shows.Suddenly he was in the circle of showbiz personalities like Peque Gallaga, June Keithley, Mitch Valdez, Jaime Fabregas, Joonee Gamboa and Margie Moran.

In the then weekly show called “Changes,” he met director Gallaga and learned camera movements by just watching behind the camera. “I learned many things from him, especially his patience when things didn’t work. He really worked fast because he knew what he wanted.”

What beckoned after his retirement was harsh reality.

After he retired, he was jobless, had no retirement benefits, no insurance and no monthly income.

“After serving in the altar of dance for more than 20 years, I was on my own with my wife and children who learned how to survive outside the arts. I was penniless, but the pressure of having to be in good shape for opening nights was finally gone. I felt so relieved. How I wished that in the future, the government would help performing artists retiring from the concert stage.”