‘Psssst’: Serendipity, art, and the road to the Venice Art Biennale

As soon as I stepped into the Artiglierie of the Arsenale in Venice, Italy—site of the Philippine Pavilion at the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia, titled “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/Waiting just behind the curtain of this age,” which closed last Nov. 24—I quickly understood just what the organizers meant by “immersive.”

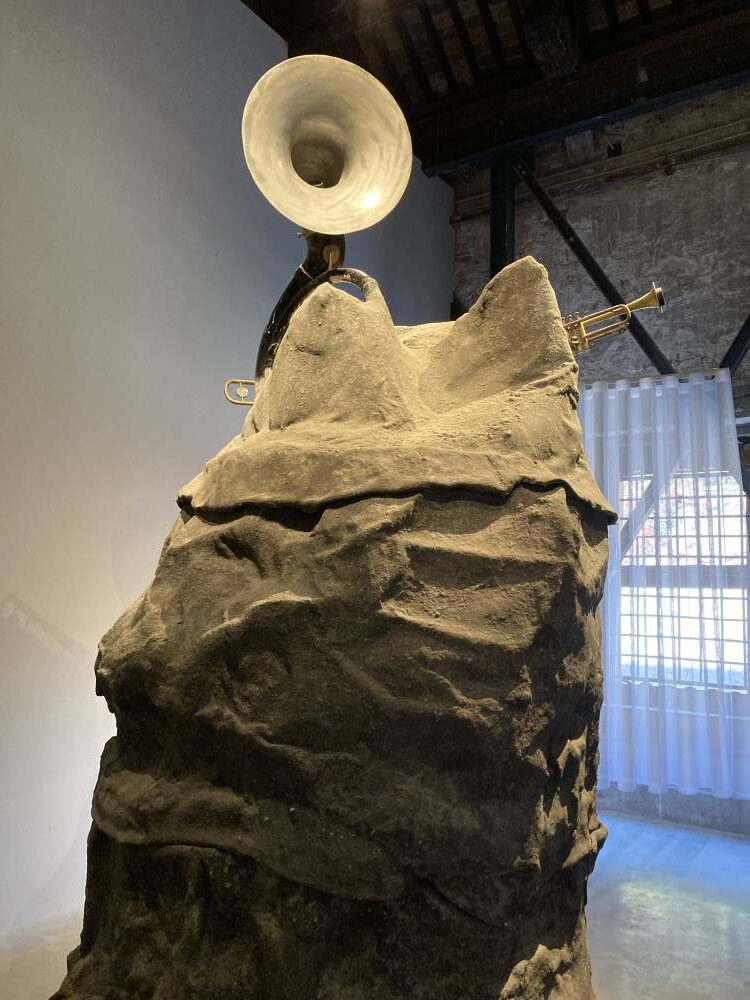

A “psssst” sounded loudly from a resin rock to the left of one entrance, with a tuba protruding from the top—so loud, several people also turned to look. That came with other sounds—bird calls, running water—all delivered through 12 speakers installed in the 330-sq m space.

“Your experience of the entire pavilion will depend on which sound activates first when you’re here,” said curator Carlos Quijon Jr., “because we also wanted the experience of you choosing to follow which sounds.”

In his curatorial statement, Quijon wrote, “Through this newly commissioned video work, a mise-en-scène of textile panels and fiberglass boulders, and a reworking of an existing work, (artist Mark) Salvatus explores the ethno-ecologies of Mount Banahaw—how the surrounding more-than-human world interfaces with cultural imaginations: from how people perceive and act on the environment to how environmental considerations shape cultural life.”

The rocks, diaphanous curtains separating but not quite concealing different sections, a video taken on Mount Banahaw showing how lush it remains and how musicians continue to revere it—all were elaborations on the natural landmark’s “profound connections to broader narratives of faith, mysticism, and revolution.”

Backyard

Salvatus, who lives in both Lucban, Quezon, and Cubao, Quezon City, grew up with Banahaw in his virtual backyard. “When I was still young, I already had this idea that I wanted to be an artist,” said the 44-year-old advertising graduate of the University of Santo Tomas, who actually taught the subject for a while before doing his first art residency in Korea, later being mentored by the likes of Bogie Ruiz and Karen Flores in the collective Tutok. Among many others, he also did a residency in Japan, where he met his wife Mayumi, an art curator; the couple have a son, Yoji.

His father was also a collector, so Salvatus, who calls his particular practice “salvage projects” (a play on his surname—“Branding!” he says with a laugh), likes to pick up all kinds of “trash” and objects. The lack of formal training might have proven to be an advantage.

“In a way, art is a Western concept, so even in the educational system in the Philippines, the fine art is Western. So I got influenced by the practice itself, by making, experimenting. Not the theory, because anyone can get the theory. But the practice itself is something personal, but also social—where you’re based, where you live.”

Salvatus betrays a refreshing lack of ego in his preference for ephemeral installations or projects that may not be in a museum for eternity, citing the “instability” of the effort, and which often invite collaboration from the public.

“I’m also thinking about how the Pahiyas Festival”—which he credits for his earliest exposure to art—“is not fixed. It’s just hanging. It’s installed temporarily. So I mix what I know in the Philippines, like Lucban, and my tradition, and art history, through experimentation. Through everyday objects, photographs. So everything is possible. Like when you start something, you don’t know how many layers you’re going to mix.” The open attitude is even more evident in how, when kidded about his art being “pang-Biennale lang,” he notes wryly, “Oh, I wouldn’t mind being collected, too!”

In the video, there are unexpected, almost funny scenes of musical instruments peeking out from behind trees, or randomly moving through a frame. “I’m interested in those small instances that you observe—someone’s staring, someone’s sitting. It’s a small gesture that we sometimes ignore in reality,” Salvatus said. “So art can be a platform to show this, to create some kind of new connection.”

Bigger picture

Salvatus remains cautious, however, not to highlight universalities that speak beyond his experience as a Filipino. “As an artist, I only know how to represent myself. It’s also a big problem with identity. I mean, I don’t want to save anyone. If you make a work that’s already a representation, parang it’s didactic na. But through this abstraction, many new connections can be brought up.”

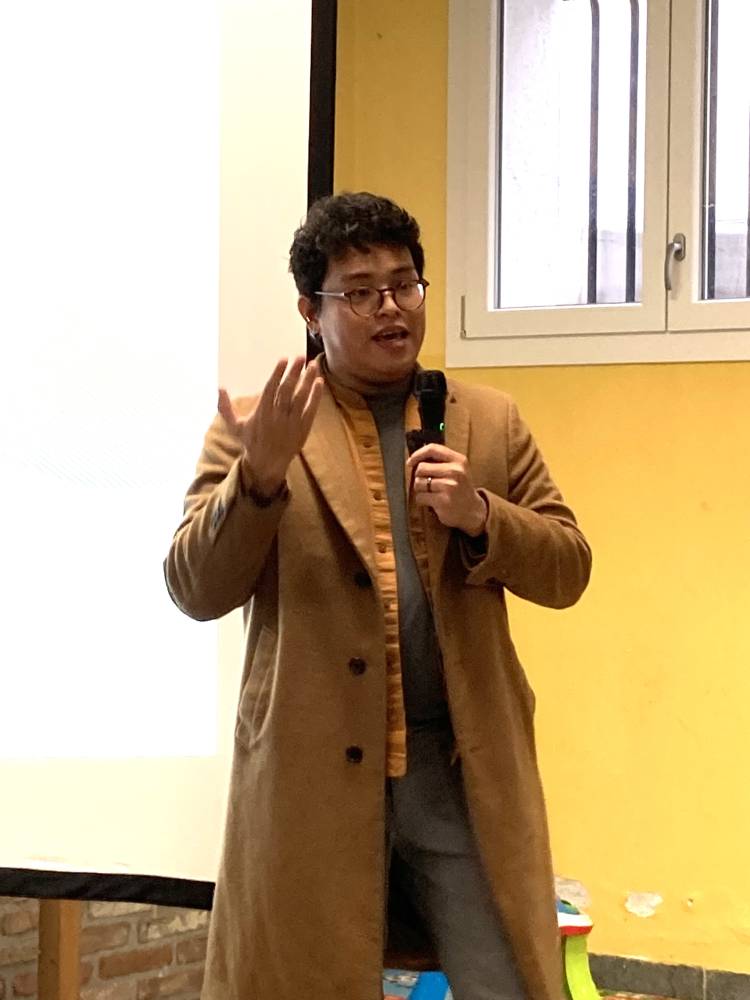

The job of seeing that bigger picture, while still letting the artist forge the path, likely belongs to 35-year-old Quijon, who actually put on hold a Contemporary Modern Art Practices residency at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and another one at the Singapore Art Museum to handle the Philippine Pavilion.

Quijon is cognizant of what “national” encompasses in this day and age. “For sure, our national history was written by maybe Spanish- or Western-educated intellectuals who have picked and chosen what will represent the story. I feel like it’s also interesting to have that conversation. We are claiming that this is still national history, but it’s not the national history we are used to. A pavilion is good when things can latch on to it—different discourses, different interpretations. I’m not interested in negating the national. I’m interested in how to make it a more plural conversation.”

Neither does Quijon want to fall back into the fist-raising mode of former colonies. “We’re not really decolonial in many ways. We’re not here to sever ties. We’re here to just ask, can we have better lives? At this point, anti-colonialism would be a little clichéd.”

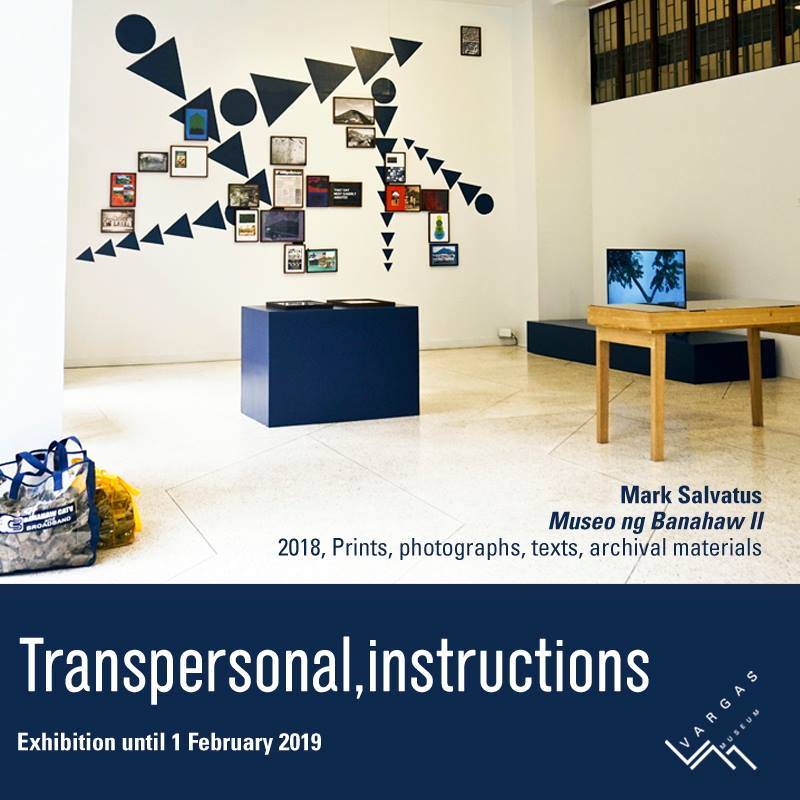

When the call was made for proposals for the Philippine Pavilion, Quijon had already been interested in Salvatus’ “Museo ng Banahaw,” an evolving installation of objects referencing the mountain, from family mementos to commercial products like mineral water and spas. The two had already met some years earlier. “I told him, ‘I’m interested in this project. If you want, we can expand it for the pavilion, but we’ll need to think about this, this, and this.’”

When formulating the proposal for the pavilion, Banahaw was foregrounded for a number of reasons, Quijon said. “This is the National Pavilion, so anything that you put here will be national. But we wanted to delay the story of the nation through a province, and Mark’s practice as an artist who was born and raised in Lucban is more intimate. He had started to think about the mountain in his practice two or three years before we started thinking about this project. So, it was also ripe for that kind of free imagination, meaning he had a handle on the material already.”

It didn’t hurt that the two have similar open approaches. “In both Mark’s and my practice, we like serendipity a lot. So, while we were digging, we started to get to know more about the many relationships.”

Idealization

These learnings informed how the artist and curator viewed the succeeding Lakaran Lecture-Workshop Series, the Philippine Pavilion’s concluding activity, which visited five Filipino communities from northern to southern Italy.

“We decided to think about the workshop,” Quijon said. “Like, how do we try to understand the position of, for example, children of OFWs who have never been to the Philippines? There’s often an idealization of the Filipino because they don’t have any idea of what the Philippines is like. So for me, that’s another interesting layer of thinking about the nation. Because, however abstract and indirect these relationships are, they are part of the national imagination, whether we like it or not.”

Quijon actually studied comparative literature and even law, and was a poet before becoming a curator with a focus on Southeast Asia, mentored by curator, critic, and professor Dr. Patrick Flores. Quijon said there are a lot of young Filipinos pursuing the discipline—“but there are only a few international practitioners because it’s hard to break through.” In the 2010s, there were a lot of curatorial workshops that helped open doors for him. “It’s an exceptional position for me, because not everyone translates the interest to practice.”

So what does it take to be a good curator? “I think I have no idea,” Quijon said with a laugh. “I think I’ll be a Miss Universe and say self-confidence, in a way that you don’t feel anyone’s talent is a threat to your art. A good curator has to have that kind of equanimity.”

Home is still the Philippines, as “my main interest is still Southeast Asia. It’s something that I think about in my practice. The Philippines is also, for me, still the most interesting place. We have a lot of things happening.”

The Philippine participation at the Venice Biennale is a collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, the Department of Foreign Affairs, and the Office of Sen. Loren Legarda.