Ramon Orlina’s lifetime of clear visions

I can do anything in sculpture with whatever material … except one—glass! For that you have to go to Ramon Orlina.” That’s a quote from the late great National Artist for Visual Arts Napoleon Abueva, and there can be few grander endorsements of the internationally recognized Filipino glass sculptor, leader, philanthropist and art innovator.

Orlina is marking his 50th year in the field with “Ramon Orlina: Visions in Glass,” a landmark 570-page book published by the artist and the Museo Orlina Foundation Inc. Written by Cid Reyes, designed by Dopy Doplon, and featuring photographs by Orlina, Bong Peñas, and a number of other accomplished lensmen, the book is also a labor of love for Orlina’s wife, Lay Ann, who acted as project director. The book will be launched alongside an exhibit of the same title on Oct. 9 at the Orlina Glass Lounge at Manila Art, SMX Convention Center, SM Aura. The exhibit will run until Oct. 13.

With 57 very short chapters on everything about the artist—from his early life and career as an architect, to his pivot to artmaking during martial law, his discovery of a medium artists were generally afraid to touch and his evolution into an accomplished sculptor with worldwide collectors and commissions—“Ramon Orlina: Visions in Glass” is the definitive record of a maverick of Philippine contemporary art who conquered a fragile, mysterious medium and made it bend and soar in his hands.

Milestones

“Like many artists who have had an active and fruitful career, I have long felt the need for a book that chronicles the milestones of my artistic journey—a journey that has now spanned almost five decades,” Orlina says. “Collectors and followers of my work have often asked when such a book would be available, and the idea became a necessity as my body of work evolved.”

Orlina reveals that he actually engaged Reyes as early as 2014. “Can you believe it? He began drafting the manuscript that same year. And yet, here we are—10 years later—finally sending the book to print.” Turning 80 last January gave the artist a new sense of urgency to get the job done.

“Orlina broke new ground—indeed, he broke a boulder of recycled glass and elevated humble material into magisterial masterpieces with his artistry and creativity,” affirms Reyes.

“ … When I am actually cutting the glass, I must play with the light,” the artist says in an opening quote. Words from colleagues and art advocates, including the aforementioned Abueva statement, affirm his stature.

“Ramon Orlina has transformed glass into a medium of sublime beauty and elegance in his pursuit of artistic excellence,” writes Jeremy Barns, director general of the National Museum of the Philippines.

“Looking at masterpieces that touch heart and mind, perhaps with a hundred facets quivering in the light or with shapes curving smoothly and sensuously, one forgets that the artist has labored over that hardest and most brittle material that is both tough and delicate,” says Cultural Center of the Philippines chair Jaime C. Laya in the preface.

The book begins at the beginning—Orlina’s birth in 1944 to parents from Taal, Batangas, a legacy he would honor years later when working for the conservation of his home municipality, and how he drew superhero characters as a boy, but was already in awe of modern buildings. He studied architecture at the University of Santo Tomas, where again, he would return in 2011 to help celebrate his alma mater’s quadricentennial anniversary with a massive 10-meter carved glass and bronze monument, “QuattroMondial.”

Just when his architectural career was taking off, martial law saw business grind to a halt. “The lack of activity daily contributed to the numerous sleepless nights and overwhelming feelings of frustration and desperation that followed martial law,” writes Reyes. “It was the helplessness of someone aware of his creative potential, but still stifled by political events beyond his control.”

Uncertain times

Uncertain times pushed the artist in Orlina to the surface, and he contacted his glass suppliers to provide him with the unusual “canvas.” In 1975, he had his first one-man show, “Reflections,” at The Gallery of the Hyatt; an early work titled “Gumamela,” from the collection of the late Chito Madrigal Collantes, reveals a tentative hand that hinted at the power of the medium. “Rainbow,” from the Evelyn Camus Alcantara collection, was more geometric, already leaning towards abstraction.

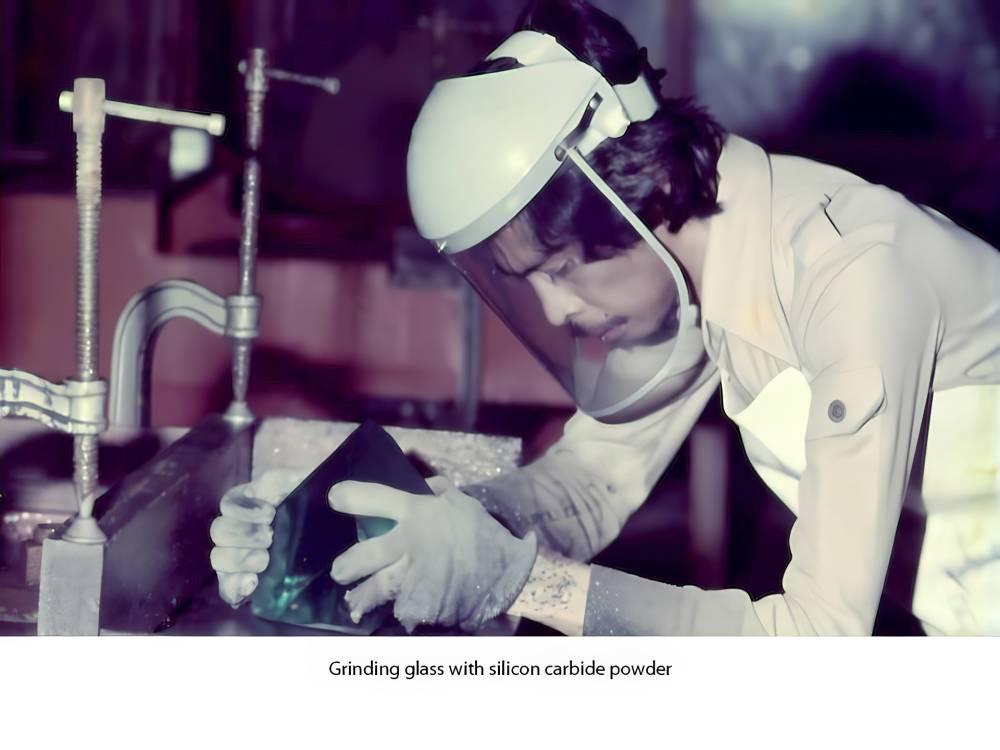

Orlina’s fateful meeting with Victor Lim, president of Republic Glass Corp., the country’s largest glass manufacturer, started the artist on his journey of self-study. He was given access to the glass factory and discovered cullets, chunks of glass waste, by-products of manufacturing.

“The Orlina phenomenon may be perceived in the light of the recycling process that goes on all the time in the Third World as a strategy of survival,” observed the late art critic Emmanuel Torres. “In Orlina’s case, it is recycling with an aesthetic vengeance.” A tribute to his benefactor, 1978’s “Tribute to Republic Glass,” is a dramatic thank-you for the partnership that spanned decades.

The archival photographs alone make the book a collector’s item. Doplon effectively opens chapters with generous spreads framed by Orlina works, and many more are preserved for posterity on the pages. There is “Arcanum XIX: Paradise Gained,” first commissioned for the lobby of the Silahis International Hotel, but now in the Museum of Natural History. There is Orlina on a study tour of Prague, where he met renowned Czech glass sculptors; there are reproductions of his Fourteen Stations of the Cross for San Beda Alabang, when he worked in stained glass but with a sleek, contemporary touch.

In 1983, for the Greenbelt Chapel, he delivered a quadruple whammy of a glittering altar base, a stained-glass skylight of God the Father, a massive Mudras cross and a stunning Dove of Peace sacristy. The chapel would prove significant; after heading to Singapore for two commissioned works in Orchard Road malls in 1985–1986, Orlina met a United Kingdom-educated Malaysian lawyer named Lay Ann Lee, who liked his work, and they were married in the Greenbelt Chapel the year after.

Doting family man

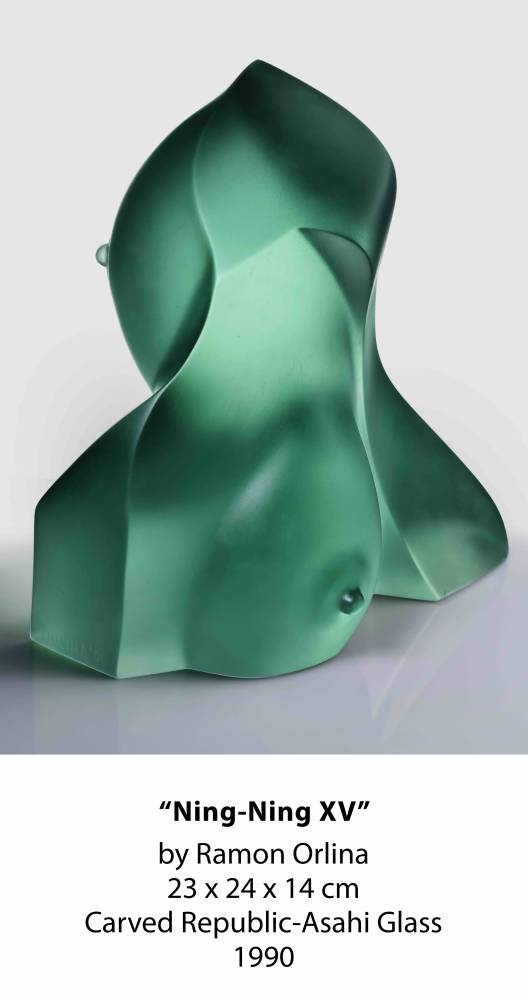

Several chapters point to Orlina as a doting family man. First daughter Naesa would inspire an artwork named after her, an exquisite series combining polished and frosted surfaces exhibited in Manila, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. Second daughter Ning-Ning would lend her name to stunning works featuring female breasts. Third daughter Anna and only son Michael would follow in their father’s footsteps, taking on glass sculpting, with their works featured in the book. Orlina would sculpt nudes, lovers, pregnant women, mother and child images, even father and child versions.

He never stopped creating, experimenting, innovating and the reader is awed at how prolific and consistent Orlina has been. “Oneness,” a metal and glass work for the sixth Asean Sculpture Symposium, features metal birds, representing the different member nations, afloat over a glass base. He etched the tattoos of ancient pintados on glass surfaces; he worked with Swarovski crystals and clear optical glass.

He delivered commissioned works for the Tower Club at PhilamLife Tower in Makati and the Singapore Art Museum, and created an awesome, 1.2-ton, 9-foot-tall Risen Christ for the Edsa Shrine that reverberated with holy power. He even designed the Perpetual Cup Trophy of the Philippine Basketball Association (PBA).

In 2000, Orlina marked 25 years of art by breathing new life into past series, and photos of his silver-and-glass works to mark the milestone are in the book. “Nude Dancer” is a sensuous glass figure surrounded by curving metal bars, while “The Coexistence” features colored spheres entwined with stainless steel.

Five years later, for his 30th year, he showed at the Ayala Museum, playing once more with colored glass, seeing double with duplicates in glass and bronze and creating a dramatic menagerie of horses, carabaos, fish.

He would go on to hold two-man shows with the likes of National Artists Romulo Olazo and Arturo Luz, but was never above having fun, collaborating with jewelers for pieces with whimsical names like Jolina and Beyoncé.

Museo Orlina

In 2012, the artist finally opened a worthy home for his prodigious oeuvre in Tagaytay, Museo Orlina. It has become a permanent showcase as well as an art hub for special events. And still, Orlina remains current.

At age 75 in 2019, he showed 20 new works at the Manila Art Fair, including a giant chess set that stole the show. In 2021, his work “Hidden Treasure” inspired a nonfungible token. Indulging his passion for art cars, Orlina decked out a limited-edition Volvo like a Piet Mondrian painting. He even invited National Artist BenCab to emblazon Orlina’s vintage Volkswagen Beetle with images of BenCab’s iconic “Sabel.”

Looking back on almost 50 years of a remarkable career and legacy, documented for the first time in a single volume, the reader comes to a fitting later chapter, “Duty to Serve.” It talks about Orlina’s various advocacies, such as with the Taal Basilica Rescue and the Concerned Citizens Against Pollution, and most recently, championing the idea of intellectual property and the artist’s right to earn each time a work changes hands.

“We didn’t want just an art book filled with images of my work,” Orlina says. “We aimed for something deeper—an almost biographical narrative supported by archival materials that Lay Ann had meticulously preserved over the years. The book needed to tell not just the story of my art, but the story of my life.”

It’s a meaningful latter trajectory for an artist who still seems at the peak of his powers—this time, taking every opportunity to use his influence to do what’s right. Like his beloved medium of choice, Ramon Orlina’s place in Philippine art history remains solid and clear.