Reflections on protests (and slow progress)

A couple of years ago, in a silly, shallow bout of ennui, my mom lent me Immaculée Ilibagiza’s memoir “Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust.” “You think you have problems?” she says. “Read about the Rwandan Genocide.” I only recently picked it up and finished it in a day. The book haunted me to the point I had sleep paralysis—not with ghosts, but with the horrors of the 1994 genocide: Hutu killers hacking Tutsi bodies with machetes, gunning down civilians with machine guns supplied by the government, and the streets piled with corpses, some 18 meters high, with a black blanket of flies.

For three months, Ilibagiza hid silently in a tiny three-by-four-foot bathroom with seven other Tutsi women, lice crawling over them, while murderers—many who were childhood friends and neighbors—were a thin wall away.

And yet, she forgave. She prayed the rosary constantly, and later admitted she actually missed that time in hiding, as she was so close to God. I couldn’t believe it. Post-genocide, now working for the UN, Ilibagiza was offered opportunities to avenge the killers of her family, but she declined. She even verbally forgave, face to face, the man who murdered her mother and brother. She forgave, instead of letting her rage fester.

Forgiveness versus rage

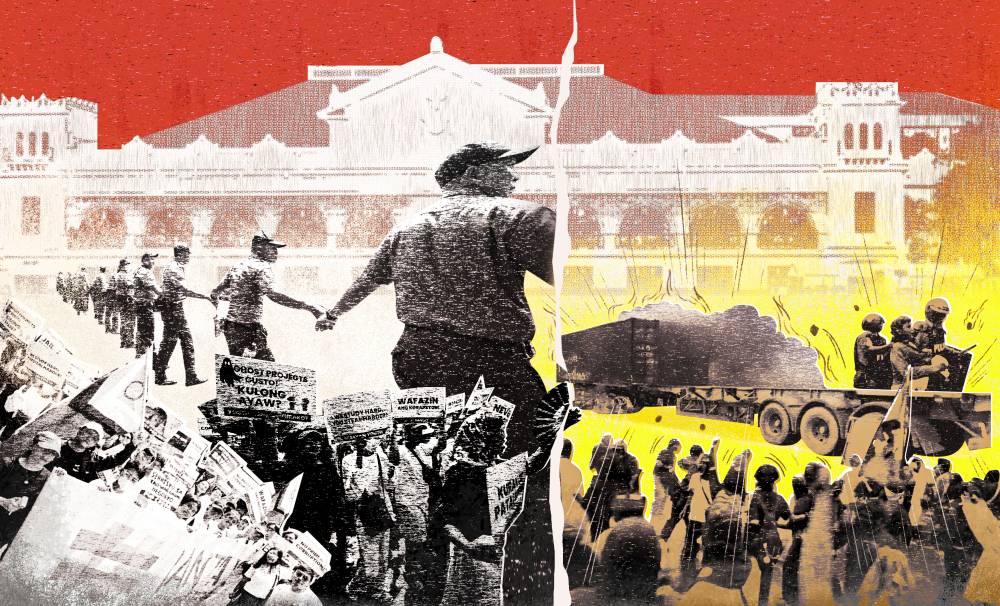

So if the Rwandan genocide is any example, violence is not the answer. The book was fresh in my mind, watching the rallies on Sept. 21 at both EDSA and Luneta. The protest chants were so full of anger, confronting corruption and state neglect, especially around issues like flood control. But these protests were largely peaceful compared to the molotov cocktails and public property desecration in Mendiola.

Partido Sosyalista is one group that condemned violence not of the protesters, but of the police. As their statement put it: “Corruption is an act of aggression—an act of class war—against working people. Politicians and contractors embezzling public funds are effectively harming thousands of ordinary people by exposing them to disasters or by taking money away from public hospitals or other essential social services,” the group wrote.

“Engaging in civil disobedience, especially as direct action, is a form of protest that is an understandable and perfectly justifiable response.”

They have a point, too. So, where does forgiveness come in? And where does progress? How do you balance peace with wild, justified rage, as Filipinos continue to suffer from the withheld wealth of our government?

Do we wait patiently for another peaceful EDSA? Or is a violent revolt the only way to uproot injustice?

Historical lessons on protest

History shows the consequences of rage as well as the power of disciplined, collective action. The French Revolution, for example, overthrew a system, but its “Reign of Terror” devolved into massacres and civil war.

In contrast, Martin Luther King Jr. built a philosophy of nonviolence and achieved meaningful change in the American Civil Rights Movement. He described nonviolence as “a powerful and just weapon, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.”

Philosopher Hannah Arendt made a similar distinction: “Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent.” True power, she argues, comes from people acting together in concert, while violence is merely an instrument. The most effective protests, therefore, are not those that inflict the most damage, but those that generate new forms of social and political power.

What protests really achieve

Eleanor Pinugu, in a recent Inquirer Opinion piece, reminds us that protests do matter, though not always in the way or timeline people expect. She writes: “As difficult as it is to believe at times, protests do work. Political scientists note, however, that their impact does not always unfold in the outcomes and timeline that people imagine… sustained protests slowly erode the foundations of legitimacy that authorities rely on to govern.”

I’m no saint, and patience is one of the values I lack most. Then again, it feels weak to say “back to regular programming” after the rallies against massive corruption and pathetic flood control.

I guess that is the tension that I and many other Filipinos will keep wrestling with: between rage and forgiveness, between wanting progress now and knowing it takes time to “slowly erode” that foundation of corrupt officials.

Corruption is a decades-long, deeply embedded issue in our country. And it looks set to be slow-moving work.

While learning to hold both rage and forgiveness at once, the greatest challenge may now be patience. And maybe the best way to channel that righteous anger is through principled action, conscience strong and intact for the long, drawn-out fight to justice ahead.