Remembering Gregoria de Jesus

May 9 this year should be a special day not only for women, but for every freedom-loving Filipino, for it marks the 150th birth anniversary of a courageous woman who was responsible for safeguarding the documents of the Katipunan. She risked her own personal safety, always ensuring the documents were safe during inspections by the Guardia Civil.

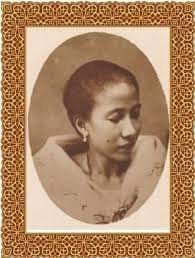

It is a good time to recall what Gregoria de Jesus, known as Oriang and, in Katipunan circles, Lakambini, went through during the years of the Revolution. Aside from the usual description of her as the Mother of the Revolution, it is interesting to know her better in her own words in “Mga Tala ng Aking Buhay,” her autobiography written at age 58.

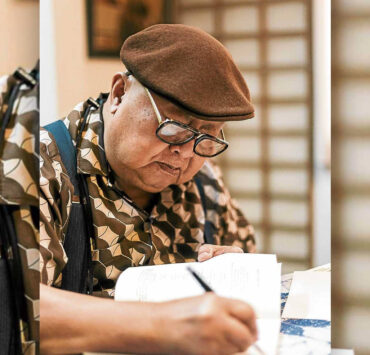

My reading of Oriang’s memoir is from the English translation of the University of the Philippines history professor Leandro H. Fernandez published in the June 1930 issue of the “Philippine Magazine,” Volume XXVII, No. 1. The original text was written on Nov. 5, 1928.

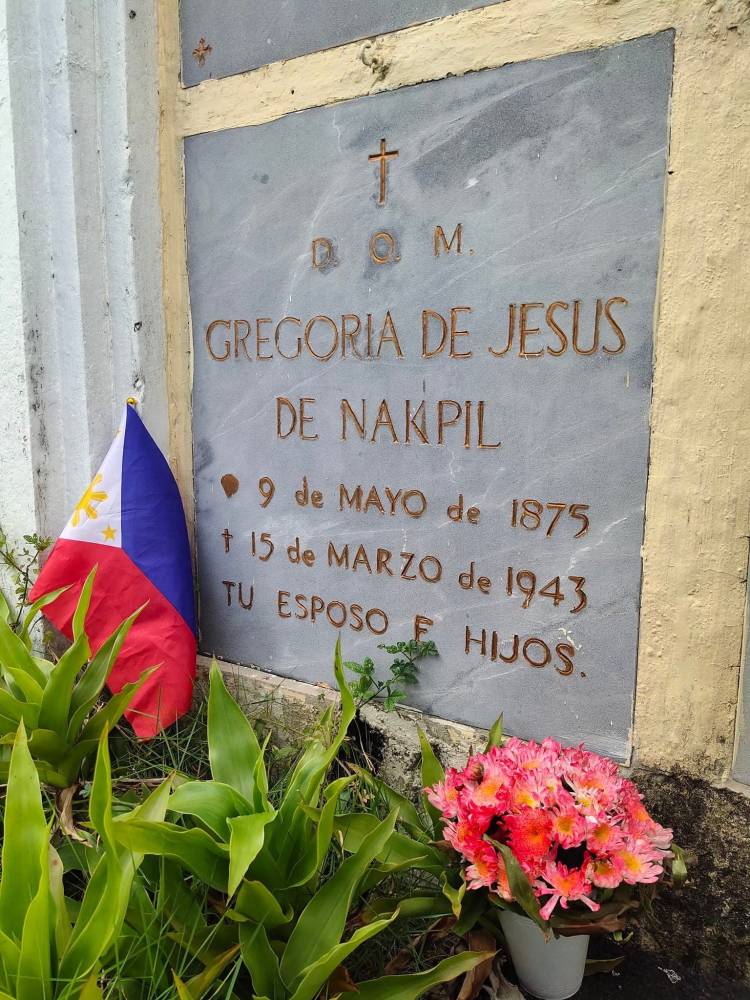

Gregoria was born on May 9, 1875, at 13 Zamora, then Baltazar, Caloocan, where she said thousands of arms used in the revolution were buried. She belonged to a middle-class family. Her father, Nicolás de Jesús, was a master mason and carpenter who later served as a gobernadorcillo, while her mother, Baltazara Alvarez Francisco of Noveleta, Cavite, was related to General Mariano Alvarez, a key figure in the Katipunan.

Intelligence and dedication

As a young woman, Gregoria was known for her intelligence and dedication. She excelled in school and even won a silver medal in an examination organized by the Governor-General. However, she eventually left her studies to allow two brothers in Manila to continue theirs. She helped manage her family’s farm and household.

When she was 18, she recalled male visitors coming to her house—Andres Bonifacio, Ladislao Diwa, and her cousin Teodoro Plata. “None of them talked to me of love.” But her parents knew Bonifacio was interested in their daughter. Her father objected because Bonifacio was a freemason, because freemasons “were considered bad men, thanks to the teachings of the friars.”

In deference to her parents, they were married in church in Binondo, but the Catholic ceremony was not recognized by the Katipunan, which performed another ceremony.

Thus began her role as Lakambini (paraluman, diwata, or muse). It may sound glamorous, but was actually a challenging and dangerous role. Recalling what she went through, she said she herself was surprised at how she survived and endured. “I had no fear of facing danger, not even death itself, whenever I accompanied the soldiers in battle, impelled as I was then by no other desire than to see unfurled the flag of an independent Philippines … ”

She had to learn how to ride, shoot a rifle, and use whatever weapons were needed, like a true woman warrior. Life was not easy. “I have known what it is to sleep on the ground without tasting food the whole day, to drink dirty water from mud holes or the sap of vines which, though bitter, tasted delicious because of my thirst.“

It is a welcome reading to take note of the details of her years as Lakambini, painting a picture that the usual Gregoria de Jesus epithet “Mother of the Philippine Revolution” does not reflect. She spoke of the birth of their firstborn, also named Andres, but nothing more is revealed—only that she had to flee from a fire and they had to move from house to house. “We were forced to move from one house to another, until one day our child died in the house of Pio Valenzuela, on Calle Lavezares, Binondo.”

Persecution and cruelty

Was it traumatic and painful too to touch on the execution of her husband? Again, she was sparing of her feelings. All she wrote was: “With respect to the controversy between Bonifacio and Aguinaldo which originated from the troubled elections held in Tejeros, and the persecution of and the cruelty committed against our family by the Aguinaldo faction, which culminated in the execution of Bonifacio, I will say nothing here, since (an account of) the same can be read in a letter of mine to Emilio Jacinto … ”

Regarding her work in the Katipunan and the fact that she worked closely with Emilio Jacinto, who lived with the couple in their house and was in charge of the printing press used by the Katipunan, she revealed that she was the first to translate or decipher the Katipunan acts in code. These were sent to her by Jacinto “with a piece of bone extracted from his thigh when he was hit by a bullet at an engagement in Nagcarlan, Laguna.”

Of her years of living dangerously to escape arrest when the Katipunan had been discovered, she wrote: “I was treated like an apparition, for, sad to say, I was driven away from every house I tried to enter to get a little rest. But I learned later that the occupants of the houses I visited were seized and severely punished and some even exiled—one of them was an uncle of mine whom I visited that night to kiss his hand, and he died in exile. My father and two brothers were also arrested at this time.”

It is interesting that she highlighted the punishment for erring Katipuneros who did not adhere to the precepts of the organization, especially those who committed adultery. The admonition read: “If you do not want your mother, wife, or sister abused, you should likewise refrain from abusing those of others, for such an offense is fully worth three lives. Bear in mind always that you should never do to others what you do not want done to you, and in this way you may count yourself an honorable son of the country.”

Gamblers were dropped from the society and reinstated only with a change of conduct.

Role model

In that era, women, like Oriang, were expected to conform to traditional roles as caretakers and homemakers. But the revolution provided opportunities for women to actively participate in the fight for independence, breaking barriers and redefining their roles in society. Oriang’s role then was certainly not deemed ordinary or conventional. She became a role model for other women daring to break out of the mold.

Her memoir also mentioned her marriage to Julio Nakpil, Bonifacio’s secretary and a general in charge of all the troops in the north. Nakpil became known as an eminent musician and composer. They lived with the well-known philanthropist Dr. Ariston Bautista and his wife, Petrona Nakpil, Julio’s sister, in what was a genteel district in Quiapo. They had eight children in that home where Julio’s family also lived. Only six lived to adulthood. She wrote with much affection about the generosity of Dr. Ariston Bautista, who sent all their children to school and “who treated me like a daughter and sister.”

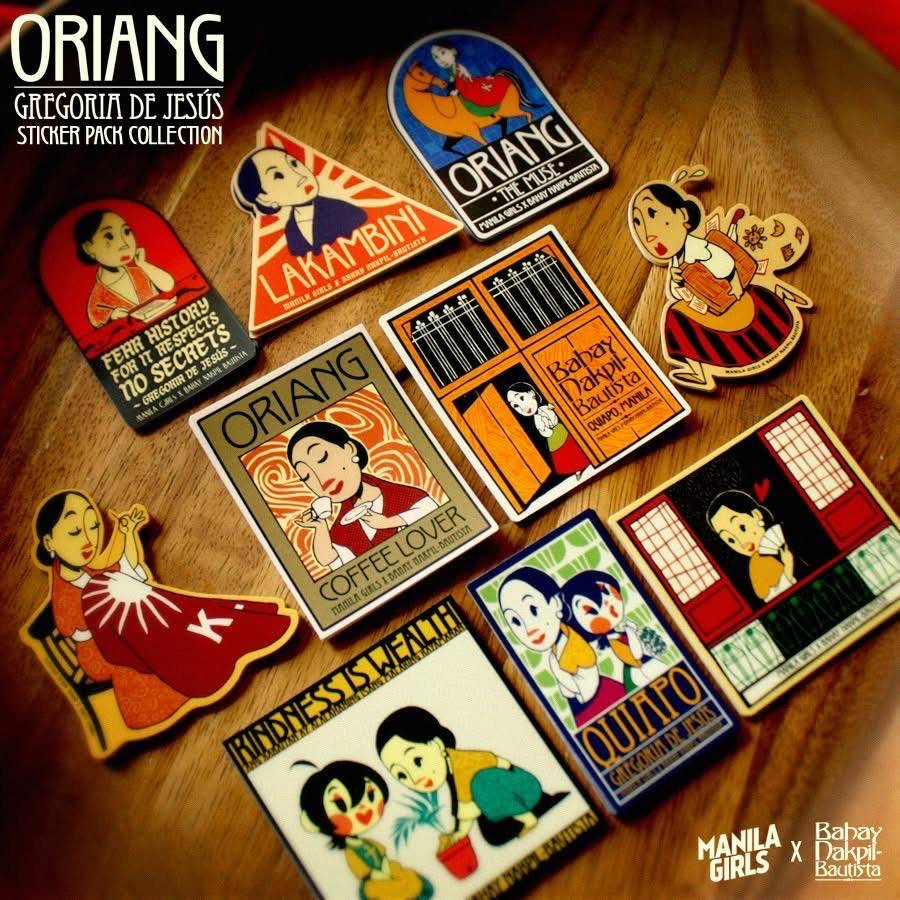

Today, that heritage house, a Quiapo landmark and historical place, is known as the Bahay Nakpil-Bautista–Tahanan ng Mga Katipunero. It is managed by Nakpil’s granddaughter, the daughter of Gregoria’s youngest daughter, Caridad, Maria Paz Nakpil Santos-Viola. In that house, today the venue for many historical and cultural events, one sees samples of Oriang’s artistry and creativity, like her small wooden sculptures. She was also known to excel in the kitchen. It is truly a place to visit, steeped as it is in history.

Stepping into the house brings one to special periods in Philippine history.

Legacy

She ends her memoir with her words of counsel to the youth, today known as the Decalogue:

Respect and love your parents, because they are next to God on earth.

Remember always the sacred teachings of our heroes who sacrificed their lives for love of country.

Acquire some knowledge in the line or field of work for which you are best fitted so that you can be useful to your country.

Remember that goodness is wealth.

Respect your teachers who help you to see and understand, for you owe them your education as you owe your parents your life.

Protect the weak from danger.

Fear history, for it respects no secrets.

Greatness begins where baseness ends.

Promote union and the country’s progress in order not to retard its independence.

Gregoria de Jesús passed away on March 15, 1943, but her legacy as the “Mother of the Philippine Revolution” invites a fuller and deeper appreciation.

Thus, the recent efforts to invite us all to immerse ourselves in the heroic lives of Oriang and Bonifacio.

There are at least two children’s books on Gregoria de Jesus. “Ang Lakambini at Ako” by Becky Bravo, illustrated by Joza Nada (Adarna House, 2016), is about Ariston who is instructed to teach Oriang how to use a rifle. The book touches on courage, patriotism, and the role of women in history.

Quite recently, Boni Ilagan’s moving play, “O, Pag-ibig na Makapangyarihan” was staged, awakening interest in the love story of Oriang and revolutionary leader Andres Bonifacio. It was a touching play, made more dramatic and nostalgic with the singing of Bonifacio’s classic “Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa.”

There is “Lakambini: Gregoria de Jesus,” the much-awaited film production of Ellen Ongkeko Marfil, which stars Lovi Poe as Oriang.

There are also initiatives in the House of Representatives and the Senate to honor Gregoria de Jesus on her 150th birth anniversary to make her better known, as she deserves to be.