Remembering Lucio San Pedro and Levi Celerio

Some national treasures come to mind in the second month of the year.

National Artist for Music Lucio San Pedro was born on Feb. 11, 1913. Later on, fortuitous circumstances would connive to put composer San Pedro and lyricist Levi Celerio in one musical orbit, their musical and personal destinies becoming linked to each other though they were born in different surroundings.

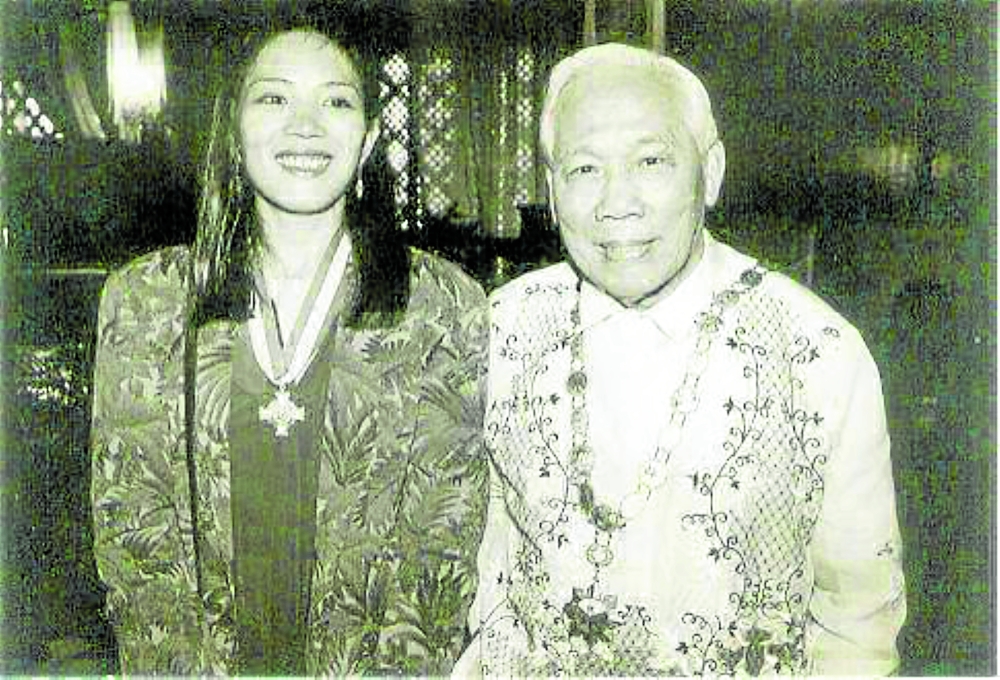

They were both declared national artists for Music in the same decade, the composer in 1991 and the lyricist in 1997.

San Pedro grew up in the idyllic town of Angono, Rizal. The lakes inspired him to write music like “Suite Pastorale,” a tribute to his hometown. He got his musical genes from his maternal grandmother whose father, Rafael Diestro, was a church organist during the Spanish regime.

The fourth of eight children of Elpidio San Pedro and Soledad Diestro, the composer recalled his early youth and how his childhood curiosity turned to the heavenly sound of the church organ. He once said, “My exposure to live music was pumping air in the church organ while my grandfather played it. When my grandfather died, I succeeded him as an organist.”

Celerio, meanwhile, didn’t have a normal family with idyllic surroundings in his early childhood. Born in Tondo, Manila, the lyricist was an illegitimate son of Cornelio Cruz of Baliwag, Bulacan, and Juliana Celerio of San Pablo, Laguna. His mother was a seamstress who played the harp and sang in the church choir. She also made pants for two Philippine presidents, Manuel Quezon and Manuel Roxas. Celerio adopted his mother’s name and met his father only many years later before he died of, in the lyricist’s own words, “overeating.”

Both artists went to public elementary schools—the composer at Rizal High School in Pasig and the lyricist in Tondo.

San Pedro’s early musical instruction came from his brother Antonio, a retired engineer. He was only 5 at that time. Antonio taught him how to play the bandurria and the octavina, instruments of the string orchestra called rondalla.

Band leader

“Group music attracted me very much when I was in the primary grades. I became the so-called band leader of young boys. We had a banda de voca in which all sorts of things became musical instruments such as sardine cans, kerosene-can covers, and the like. I myself pretended I was playing a big drum when in reality I was just beating a big bilao,” San Pedro said.

At 11, Celerio studied violin under a member of the Philippine Constabulary Band and became the youngest member of the Manila Symphony Orchestra founded by Alexander Lippay in 1926.

But like San Pedro, his aspiration to become a violinist didn’t go far. Celerio fell from a tree and broke his wrist, while San Pedro broke not just the bow of the violin but the instrument itself because of displeasure with his early solfeggio lessons.

San Pedro said, “My sister Emilia was much better in music than I was in our youth. I got a grade of 45 in music when I was in Grade 5. It’s a big surprise that I ended up a musician.”

In their early youth, however, music became a full-time preoccupation for both San Pedro and Celerio. San Pedro became a banjo soloist and enjoyed notating songs he heard over the radio. Celerio got his first break as a lyricist when he was asked to write the theme song of the movie “Dalagang Bukid.” His early success brought him in contact with other musicians who ran to him for lyrics for works in progress.

While San Pedro was winning one composition contest after another in school, Celerio was writing the lyrics for Santiago Suarez’s songs “Harana” and “Balitaw.”

The two were sidetracked by the movies—Celerio writing theme songs and San Pedro doing musical scores for the early movies of Fernando Poe Sr. Soon, San Pedro dropped movie projects and pursued serious composition. He continued winning prizes and awards in composition and received the Republic Heritage Award for his work, “Lahing Kayumanggi,” depicting the struggle of the Filipinos against foreign conquerors.

In due time, San Pedro accumulated a large body of works for voice, piano, violin, band, and orchestra, including oratorios and cantatas, the last of which was “The Redeemer.”

Celerio persisted until he had a body of movie theme songs, some of them winning awards. He became a lifetime awardee of the Film Academy of the Philippines.

Crossed paths

The paths of the two artists eventually crossed, resulting in several musical collaborations, the most notable of which is the lullaby “Sa Ugoy ng Duyan,” which has become a classic, sung by both pop and classically trained singers.

The two were destined to make music until the twilight of their lives.

Although recognized as national artists, they did not become rich. Users of their works paid them no royalties and no governmental agency or institution helped them right this wrong.

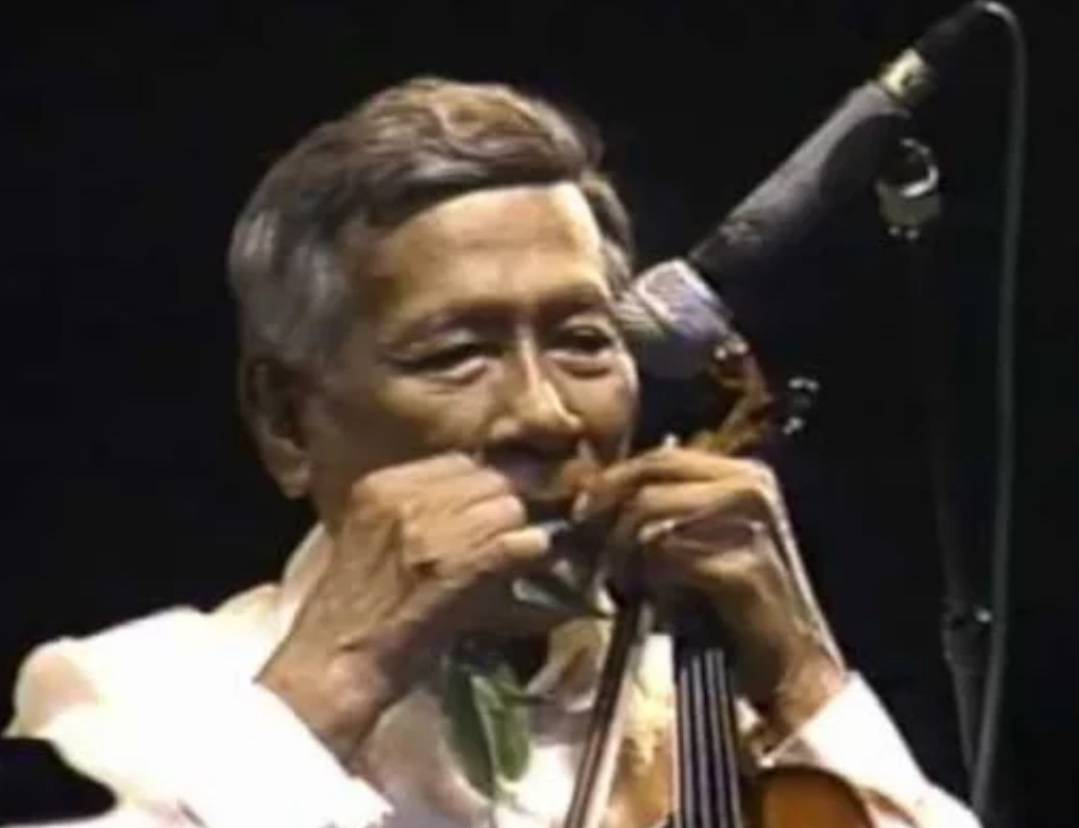

Celerio ended up playing the violin in coffee shops and restaurants and became famous for making music on a folded leaf, a feat that landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records. He appeared as a “leaf” soloist on the “Mel Griffin Show,” playing “All the Things You Are” with 39 conventional musicians backing him up.

The idea of using a leaf as a musical instrument came to Celerio this way: “In the province, when the wind blows through the leaves, you hear a distinct sound, a beautiful sound. I thought that if the wind could do that, then so could I. As you can see from what I’ve been doing, it works.”

Although he grew weaker by the day, San Pedro continued conducting bands and composing.

Celerio wrote more than 4,000 songs. He died on April 2, 2002, two days after San Pedro died on March 31. 2002. Celerio was 91, San Pedro, 89.

Music critic Antonio Hila said the composer will be remembered as a “creative nationalist who has glorified the Filipino soul through the creative use of the folk idiom in his compositions.”

Hila described San Pedro as halfway between the ultra-conservative or romantic chauvinist and the modernist or academic technician. The composer, he said, “stands on firm ground that glorifies the nationalist tradition in Philippine music.”

The government remembered San Pedro and Celerio only after they had died. President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declared April 10 a National Day of Mourning for Celerio and April 11 for San Pedro. They were given tributes as national artists for Music and Literature within two days of their burials.

As they both lived and breathed poetry and music during their lifetime, San Pedro probably even shared Celerio’s guide to meaningful existence culled from Confucius: “Choose a job you love and you will never have to work a day in your life.”