Sensory dialogue with the past

Wilfredo Offemaria Jr.’s latest exhibit, “Marahuyo,” on view at Galerie Francesca in SM Megamall till July 2, arrives at a meaningful moment in the Philippine cultural calendar. June, being the country’s National Heritage Month and the time when the nation celebrates its independence on June 12, sets the perfect stage for an exhibition deeply rooted in nostalgia and national identity.

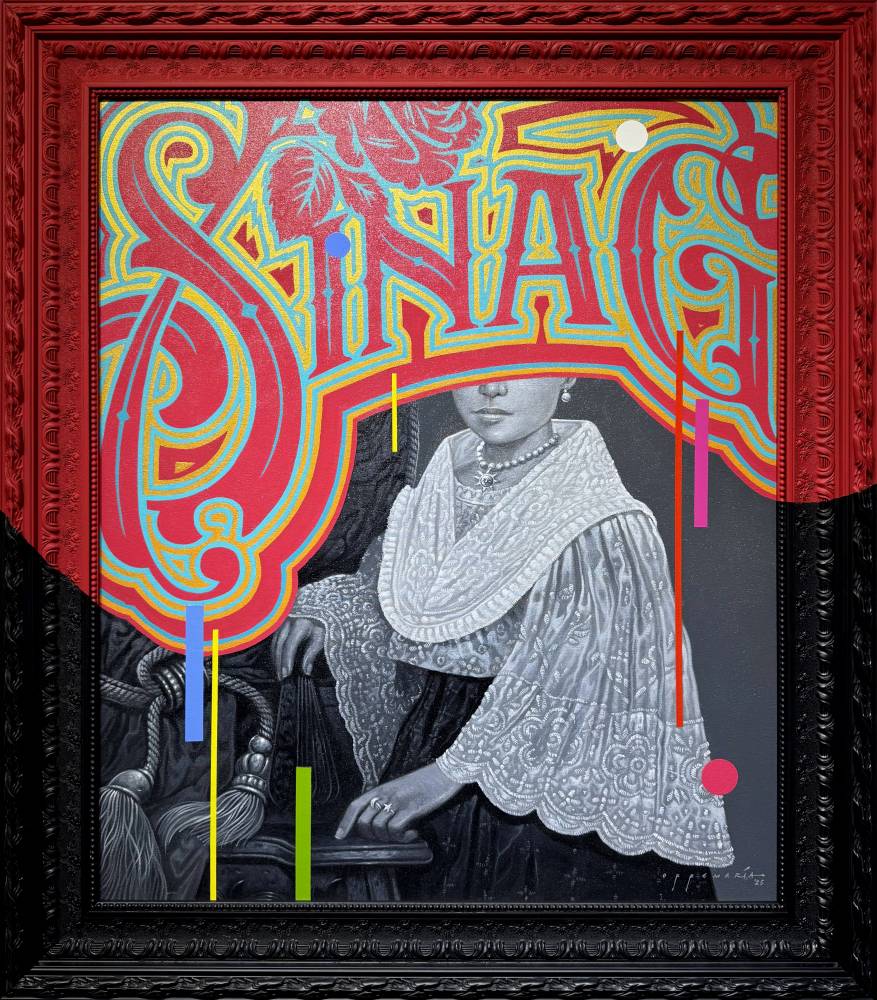

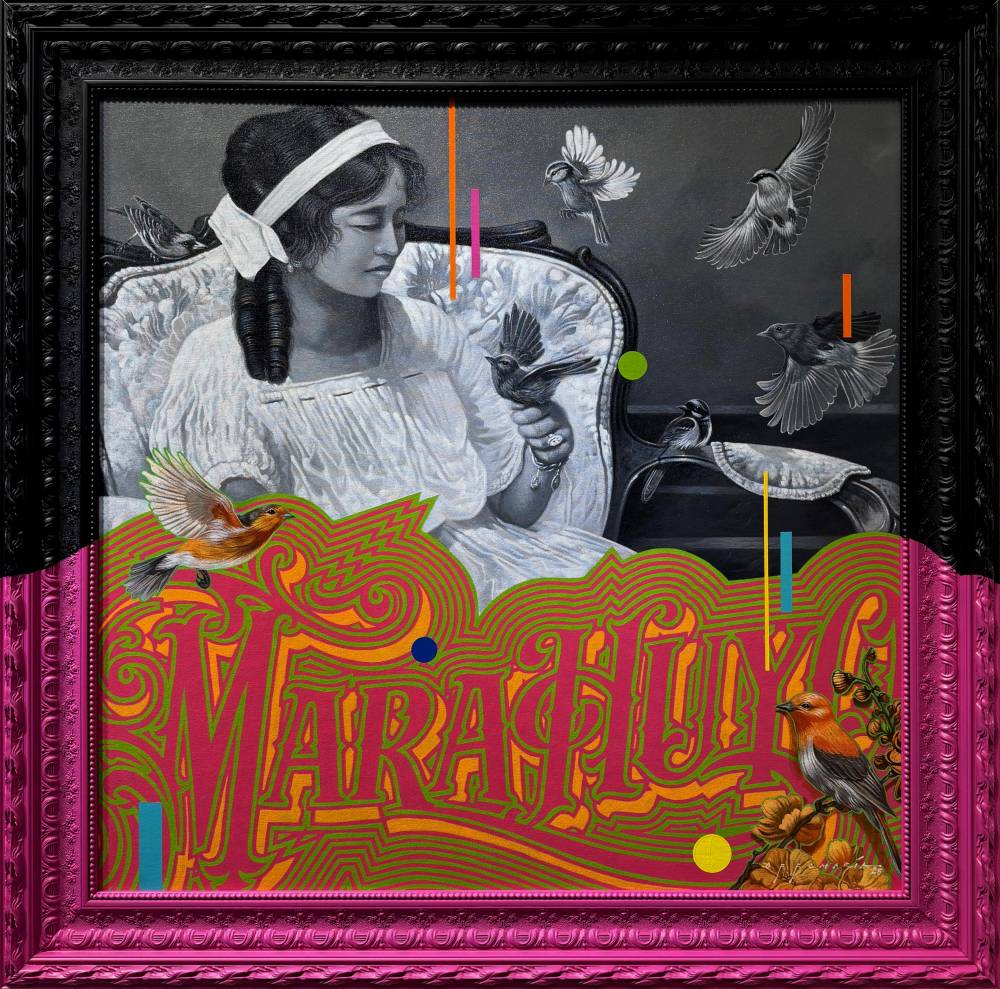

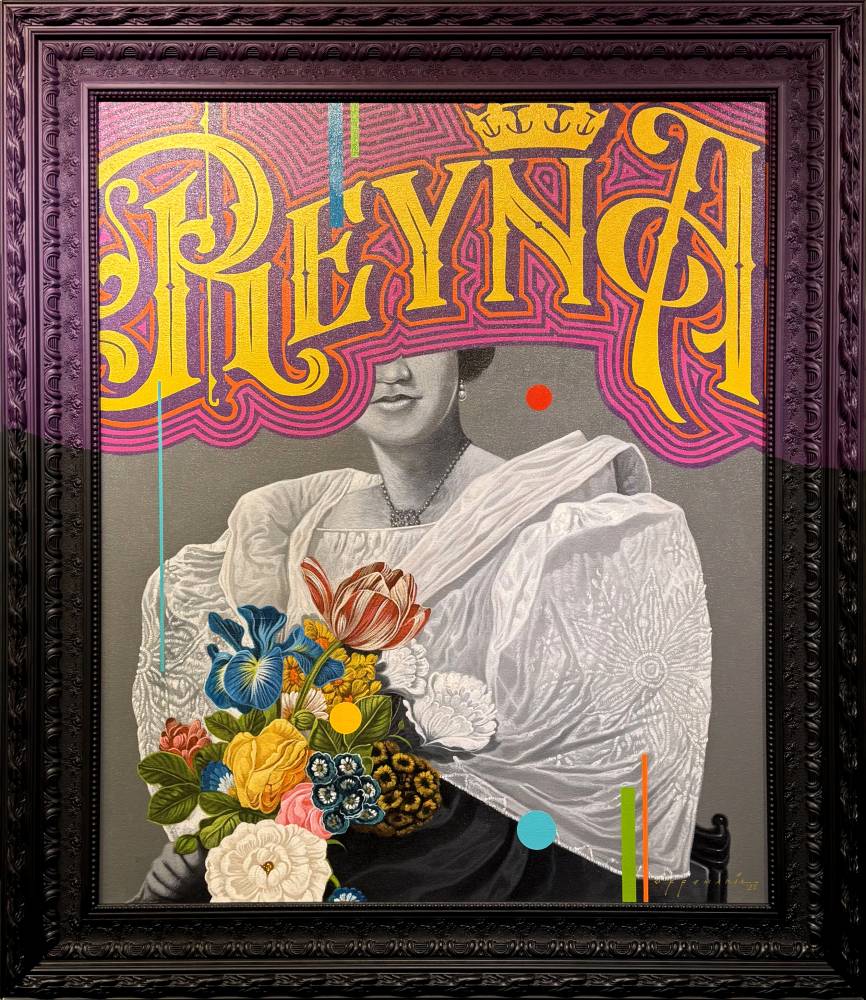

Taking its title from the old Visayan word marahuyo—meaning to enchant or seduce—the exhibit pays tribute to the grace, elegance, and resilience of Filipinas. Offemaria reimagines vintage fin de siècle photographs of women in Filipiniana dress, injecting them with contemporary life through bold graphics and color fields. The result is a striking confluence of memory and modernity, of reverence and reinvention.

The works in “Marahuyo” are steeped in a yearning for a past that feels simultaneously intimate and unreachable. This is nostalgia as more than sentiment: It is an aesthetic device and a critical lens through which Offemaria examines Filipino identity. Much like his previous sold-out show, “Visita,” which modernized Catholic liturgical art with pop and commercial iconography, “Marahuyo” continues the artist’s exploration of faith, form, and national heritage.

In “Visita,” Offemaria transformed devotional objects like the urna and the retablo into installations that played with abstraction and irony. He questioned contemporary idolatries through religious icons dressed in modern branding.

In “Marahuyo,” this strategy is revisited, but the object of meditation has shifted: Now, it is the Filipina herself who is framed, venerated, and subtly critiqued.

‘Hirang’

A standout work in the exhibit, “Hirang,” embodies the visual and thematic tensions at play. The central figure, clad in a flowing Filipiniana bodice and framed by a vintage pañuelo, is partially obscured by text rendered in a stylized Philippine Art Deco font—a typeface Offemaria himself invented and hand-painted. A maya bird perches on her shoulder, a motif rich with national symbolism. The painting’s palette evokes memory: Monochrome tones dominate the figure, while accents of lime green, cerulean, and a vermilion frame inject the scene with contemporary urgency.

Offemaria extends the homage to Filipino heritage through the use of ornate framing inspired by the Tampinco style. Isabelo Tampinco, the 19th-century master woodcarver, was known for his Art Nouveau forms imbued with Filipino motifs—bamboo, anahaw, acanthus, and other floral elements. Offemaria’s frames echo Tampinco’s curvilinear elegance, reimagining bedposts and headboards as sacred borders for these portraits of cultural memory.

Beyond the surface beauty of his work, Offemaria taps into the emotional and cultural potency of nostalgia in contemporary art. His canvases do not merely romanticize the past; they reframe it, asking what it means to remember and to belong. Through a carefully layered aesthetic—combining typographic innovation, symbolic animal forms, and vintage photographic reference—he constructs a visual language that speaks to the Filipino psyche.

Nostalgia and heritage

This use of nostalgia aligns with broader movements in global contemporary art, where longing for the past becomes a tool for critique and storytelling. Artists employ hazy aesthetics, historic references, and symbolic relics to evoke personal and collective histories.

Offemaria adds to this tradition by drawing from the rich archive of Filipino heritage, recontextualizing it in ways that are both reverent and radical.

“Marahuyo” also contributes to an ongoing dialogue about cultural heritage in contemporary Philippine art. In a time when heritage is often undervalued or overlooked, artists like Offemaria illuminate its relevance, turning the past into a prism through which we can understand the present. His reimagined Filipinas are more than portraits; they are meditations on gender, history, and the fragile beauty of cultural memory.

Through this body of work, Offemaria affirms the power of the contemporary artist as both custodian and innovator of heritage. His paintings don’t simply depict Filipina beauty; they elevate it, contextualize it, and challenge viewers to see it anew. “Marahuyo” does not offer nostalgia as a retreat but as a reckoning—a way to honor what was, while critically engaging, with what is and what might be.

In this light, “Marahuyo” is not just a visual feast but also a thoughtful, literate articulation of what it means to be Filipino in the 21st century. Offemaria stands as both witness and interpreter, using canvas and frame not to preserve the past in amber, but to keep it alive, evolving, and provocatively present.

As the country reflects on independence and identity, “Marahuyo” invites us to consider how freedom is remembered, visualized, and passed on through art that enchants, questions, and endures.