Swedish for idiots, immigrants, and me

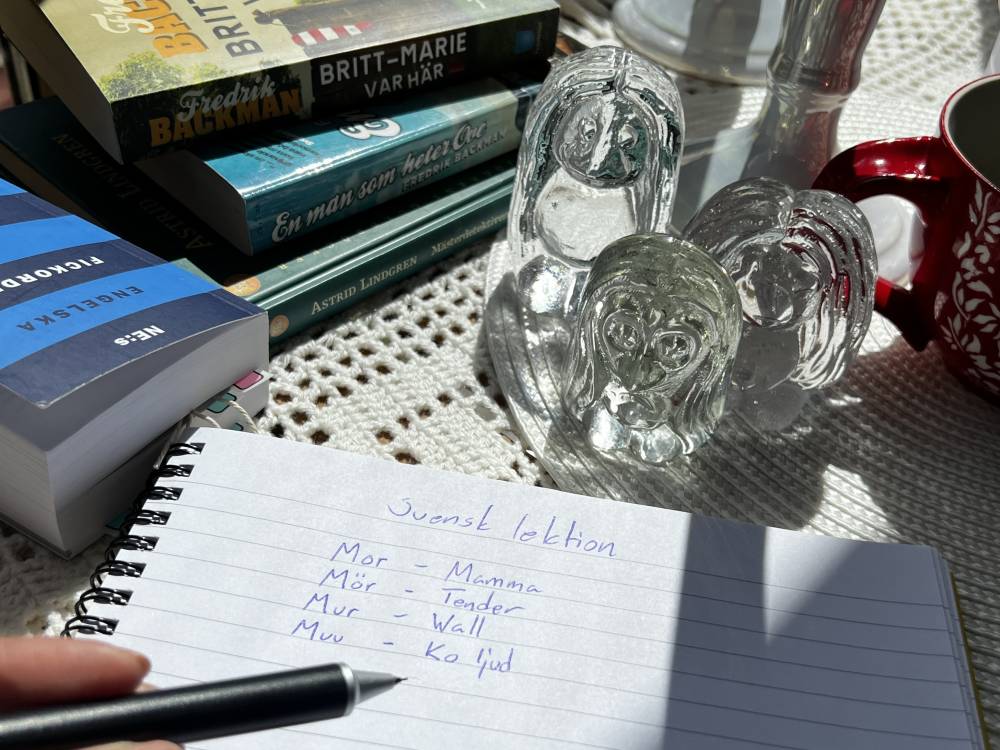

Repeat after me: mor, mör, mur, mu,” my Swedish husband Martin said. I tried, but I always end up sounding like “mu” which is the sound a cow makes—moo.

It was a week after Mother’s Day in Sweden—mors dag—which prompted our impromptu Swedish lessons at home. It has been almost three years since I moved to Gothenburg from Manila and I have been learning Swedish since, as early as the municipality accepted me to the equivalent of an elementary class. Education is free for residents in Sweden as long as you pass the class.

Most Swedes can speak pretty good English, and at one point, I thought I could get away with just English after working for years as a writer in English. The strange thing was, people always talked to me in Swedish despite my looking undeniably Asian.

I was very new in Sweden when a grandma at the tram stop asked me for directions in Swedish. Some neighbors also tried to chat, but all I did was smile because back then, I was limited to Ikea words like hej (hi) and hejdå (goodbye). A friend offered a possible explanation.

“Your look is not unusual here,” he said. “Maybe they thought you grew up here or were adopted as a child.”

So, realizing that I am not special, I took a full-time course called Swedish for Immigrants (SFI) or Svenska för Invändrare. On my first day, the intro teacher joked that SFI also means “Swedish for idiots,” and sometimes it felt exactly like that.

Extra vowels with dots on them

Learning a new language as an adult is already hard, more so studying words with extra vowels with dots on them. I can only imagine how difficult it is for people who had to learn non-Latin scripts like Japanese and Korean.

Going back to school was also a way to socialize while applying for work, because moving for love also meant leaving a career behind in Manila.

Knowing Swedish is a top tip from the networking groups I joined in my job-hunting journey. Of course, there are immigrants who got jobs, mostly in tech and engineering, even in recruitment and communication, with just English. For me, the challenge is not just rebuilding a career, but also connecting with the community and my Swedish family. I also miss watching musicals and plays, and popular ones like “Wicked” and “Dear Evan Hansen” were staged in Swedish.

But it wasn’t until I got bullied in school that I started talking Swedish at home. My teacher was on a monthlong vacation and our beginner class was lumped in with more advanced students. I had a group activity with two people–who lived in Sweden for almost a decade and did not speak English–and was trying to converse with my basic Swedish. They laughed at me repeatedly, and that sucked because I can write better than I can speak (damn vowels).

“Don’t mind them. Remember that they lived here longer and you are in the same class,” Martin said when I got home.

“Nope. We will speak Swedish from now on,” I said. Those bullies might not even remember me, but they influenced me to speak about 80 percent Swedish at home since. All the settings at our home, such as the TV, laundry, and kitchen stuff, were in Swedish anyway.

The downside of speaking more Swedish, though, was that I started hearing my English slip with a Swedish accent. Y is a vowel in Swedish (pronounced “ee” as in see) and sometimes my Js become Ys, like when I asked a person holding a cup of coffee if she was going to “yoin the fika?” or when I pointed at “Yabba the Hutt” while watching “Star Wars.”

Pinoy accent

Then there’s my Filipino accent that didn’t bother me, not even when I hear a recording of my own voice, until I had to repeat myself in English. I confirmed the accent issue while talking to a Spanish person and we couldn’t fully understand each other–and we were both speaking English. Dios mío!

My solution was downloading the Elsa Speak app and doing a short course on public speaking, which was strange since I have a degree in English, but man, I was tired of repeating myself both in Swedish and English.

Learning the language of where I live was self-care. I didn’t like feeling lost and disengaged in small talk, or the anxiety of not knowing how things worked, like health care and pop culture. One could use translation apps, sure, but context was often lost and I wanted to be more independent instead of asking my husband all the time.

I know I’ll never sound like a native speaker, but my ambition was to be fluent enough to fully integrate into Swedish society. Since taking Martin’s last name, Karlsson, I got mails in Swedish even if I wrote in English. Irene (pronounced Ih-ren, like the French Inèz) is a “vintage” Swedish name that was popular in the ’30s; I like seeing people’s faces when they meet me and see an Asian older millennial instead.

After finishing a temporary job contract, I am now studying advanced Swedish full-time while networking for a permanent role in such a tough job market (8.6 percent unemployment rate as of April, says Statistics Sweden).

With enough Swedish, I don’t feel awkward anymore when everyone laughs and it takes me a minute to catch up and laugh. My Swedish buffers and my spoken English needs clarity, but I’m getting there, and maybe someday, I’ll sound more Skarsgård with a hint of Kardashian than a baby cow.