That familiar light: Revisiting Amorsolo at Ayala Museum

A visit to Ayala Museum this season offers a rare visual respite.

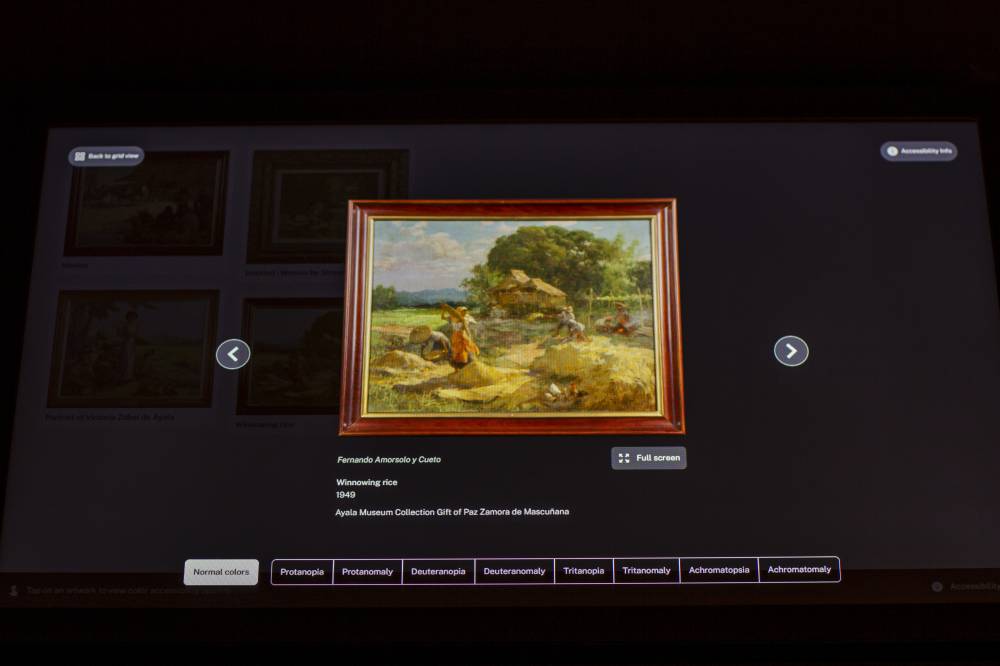

Exactly 53 years after Fernando Amorsolo was named the first National Artist for Painting, the Ayala Museum opened “Amorsolo: Chroma,” a new exhibition that reintroduces the celebrated master to a generation raised on screen light rather than sunlight. In an age saturated by blue-lit devices, Amorsolo’s canvases, steeped in the warmth of tropical light, feel almost radical in their sincerity.

Amorsolo has long been credited with capturing what many would later call the “Philippine sunlight.” In his works, light is not mere atmosphere but a living, breathing presence—filtering through mango pickers, gleaming off rice fields, and illuminating the soft outlines of a dalagang Pilipina. His light was humid, lush, and intimately familiar—worlds apart from the cold dramatics of European painting.

It was a light that helped Filipinos see themselves.

“Amorsolo: Chroma” is structured in two phases: the first, a straightforward encounter with his works; the second, a more deliberate examination of how we perceive color—and by extension, memory and national identity. For the first time, Ayala Museum incorporates interactive features into a major exhibition of a National Artist. Visitors can experience Amorsolo’s paintings through the lens of color deficiency simulations and digital tools that challenge how we have come to take his palette for granted.

Poet of color

Guests with color vision deficiency may borrow EnChroma glasses—available upon request from museum guides—allowing them to perceive a broader spectrum of Amorsolo’s world. It is a gesture that acknowledges both the painter’s own late-life struggles with vision loss and a broader commitment to accessibility in Philippine museums.

The exhibition does not shy away from putting Amorsolo in conversation with his contemporaries, a choice that invites necessary critique. It reminds visitors that Amorsolo’s signature style did not emerge in a vacuum, nor did it capture all aspects of Philippine life without omission or controversy.

Curator Tenten Mina frames this show with the essential question: In a time of hypermedia, digital filters, and shifting national narratives, what does Amorsolo’s light still mean to us? And can the mythos of the pastoral Philippines still hold sway over generations whose realities are shaped by entirely different landscapes?

“‘Amorsolo: Chroma’ is not a retrospective, rather, we highlight the early paintings of Amorsolo with particular focus on his landscapes and plein air paintings, as well as a few iconic genre paintings that illustrate light and shade of the artist’s canvas. We invite new audiences and new generations of museum goers to learn who is Amorsolo through direct observation of his canvases and understand why he was referred to as the poet of color and the master of Philippine sunlight.” Mina said at the preview.

The museum’s decision to launch the show on April 27 is not accidental. On the same date in 1972, Amorsolo was posthumously named the Philippines’ first National Artist—a recognition that formalized what the public already knew: that his vision had, for better or worse, defined how the nation would imagine itself.

Whether one leaves “Amorsolo: Chroma” reaffirming that legacy or questioning it is almost beside the point. What matters is that, for a few hours, visitors are asked to see—carefully, critically—a familiar light in a different way.

“Amorsolo: Chroma” will run at the Ayala Museum until Sept. 7, 2025.