The collected worlds of artist Phyllis Zaballero

“Welcome to my studio, Lifestyle Inquirer, I read you every morning,” Phyllis Zaballero brightly says as she ushers us into her townhouse. Partly a halfway home, it is mainly her art studio, brimming with articles of inspiration she has collected over the years.

At 83, Zaballero is what the French might call a “femme du monde”: worldly, poised, and carrying herself with a natural air of glamour and ease. She laughs, reads, and paints often, enjoys a good martini, and still insists on driving herself across Manila. Time has only refined her. Rather than simply aging like fine, mellow wine, she sparkles like champagne—effervescent, active, and full of life.

Studio as archive

The exteriors of Zaballero’s studio echo Tudor architecture, with exposed wooden beams and a steeply pitched roof. She gestures upward, recalling how she had once torn down the false ceiling, “Oh my goodness, what a lovely surprise. It was so high and in its original state—such good condition!” she gushes. “I needed height, and I want to someday hang sculptures from these hooks.”

Now, a continuous window streams light into the space, softened by stained glass panels she crafted herself. “I was given a sort of scholarship, if you like, in the south of France in Provence, to learn how to make stained glass,” she says. “It was very difficult. You have to cut the glass, work with lead, and all that.”

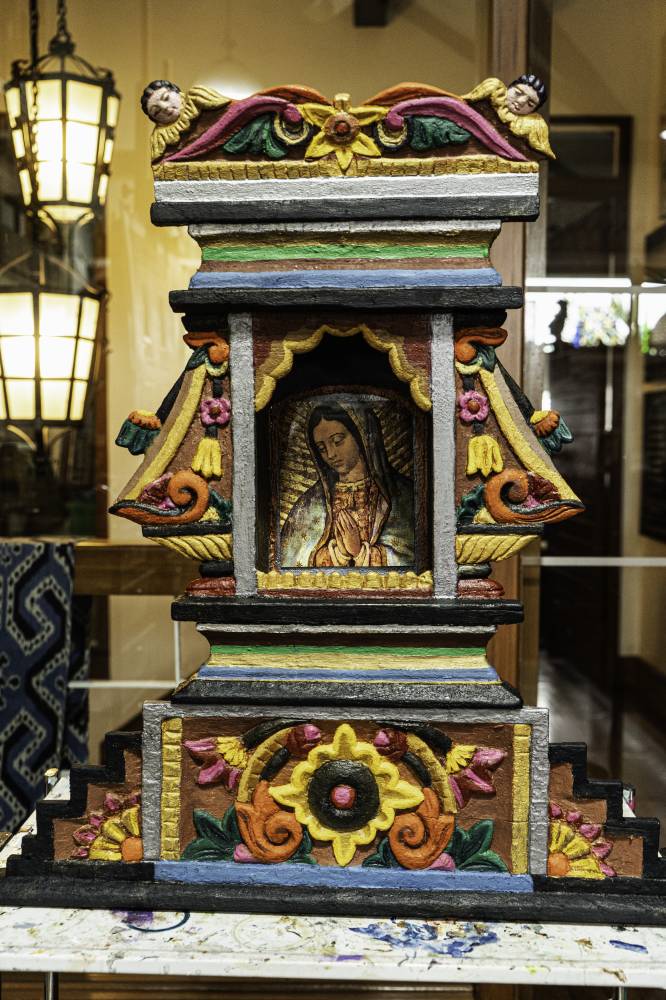

Zaballero comments on every corner of the studio, pointing out objects infused with memories. In one basket is a cluster of stones marked with locations they’ve come from. She shows us a hardy rock from her safari adventure in Africa, another plucked from Impressionist painter Edgar Degas’ mausoleum in Paris’ Cimetière de Montmartre. She uses these to weigh down her paper artworks as well.

Move through the room and you’ll see rows of teal glass insulators once perched atop telephone poles (“What do those remind you of?” she teases, hinting at their phallic shape).

“All of the little doodads are like my little collections,” she says. “I like to surround myself with things. Doodads, stones I’ve picked up on trips, little objects that might look like basura to someone else!”

But it isn’t only objects of memory. The room is, of course, a working space: long tables lined with brushes and pens, all clean, neatly organized, and ready for art-making, a massive stainless-steel sink for washing palettes, and walls of cork for notes and drafts. On the ground floor, a great wooden cabinet houses her meticulous archive, organized in a numerical system taught to her by librarians from the National Library, and adapted from the Dewey Decimal method. Each index card details where an artwork was made, exhibited, or sold, and includes a printed photograph clipped neatly to the card, ensuring no painting ever goes unaccounted for.

What many are most impressed by in Zaballero’s studio is her moving wall rack. Inspired by American painter Chuck Close—who, after a stroke, devised ingenious ways to continue working—Zaballero had her own system installed. Manufactured with Mariwasa, they installed moveable trays powered by a motor, which allows her to shift entire paintings from the first floor to the second and back again, all with a push of a button.

Her studio, strewn with articles of inspiration yet neatly organized with tools in place, reflects Zaballero’s fruitful five-decade career. “My whole life is in here already, where I can work alone in peace,” she states.

Second chances and scholarly ways

But Zaballero did not begin as an artist. After spending her childhood and adolescence with her family in Europe and the US, she returned to the Philippines in 1960 at the impressionable age of 18.

Her formative education was spent in the Notre Dame Academy in Boston, Massachusetts, and École internationale de Genève in Geneva, Switzerland. By 18, she had studied at the Marymount Colleges of Paris and Barcelona, where she was awarded an Associate in Arts degree with first honors.

Like a fish out of water, she had to adjust to the conservative society of the Philippines, which was difficult with her Western accent and definitely “je ne sais quoi” European air. By 1964, she had finished a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from the University of the Philippines. “I was miserable, miserable, miserable!” she exclaims, “because I’m dyslexic with numbers.”

Soon after moving to the Philippines, she met her future husband, charmer Toti, who became a successful banker. Together, they raised three bright boys, David, Alec, and Guido. In her book “Phyllis Zaballero,” a substantial biography written by Alfredo Roces, she was described as “a perfect little housewife.”

But that wasn’t enough. “I would get quite depressed, because there was something lacking. I knew that I had to snap out of it, you know? I was painting and taking art lessons, but that’s different.”

She explains, “A lot of women are talented… but you can’t do it on your own. I wanted to do it the scholarly way.”

So, even as a wife and mother, Zaballero went back to school, becoming a freshman at the UP College of Fine Arts. “I was the oldest person in the class,” she recalls. “I was 33. But it changed my life. I [was] a balik-aral... [but] that was also a second chance, a second life.” With that, Zaballero graduated magna cum laude and later became a professor for many decades at the same school.

She also gives firm advice to young people: “Never give in to your parents if you’re not happy with what they want you to do. You’re never too old to start again.”

Conversations across time

Fans of Zaballero would be well-acquainted with her progression as an artist over time.

While her practice shifts, her subjects are never random. Her series of “Window Series” frames panoramic views, often from travels or domestic vantage points, bursting with color and verging on abstraction. Meanwhile, her tablescapes show intimate portraits of daily life: bread glistening with butter, coffee steaming beside sugar and fruit, elevating the still-life in vignettes.

During the period of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos’s regime, Zaballero was also a staunch activist and painted distinctive works in protest, while around the time of the pandemic, she held an exhibition called “Conversations with My Masters,” where she imagined speaking with Edgar Degas, Pierre Bonnard, and Henri Matisse, reframing their iconic scenes through her own brush.

More recently, she’s been working on “Illuminations,” where she manually imposes newer works onto her older works on paper. A diptych in time will have a sketch from 1992, reframed with an ornate, pen-and-ink border sketched in 2023. “When I was a little girl, the nuns would make me copy medieval illuminations,” she recalls. “Page after page of tiny details, done by hand. That kind of discipline stays with you.”

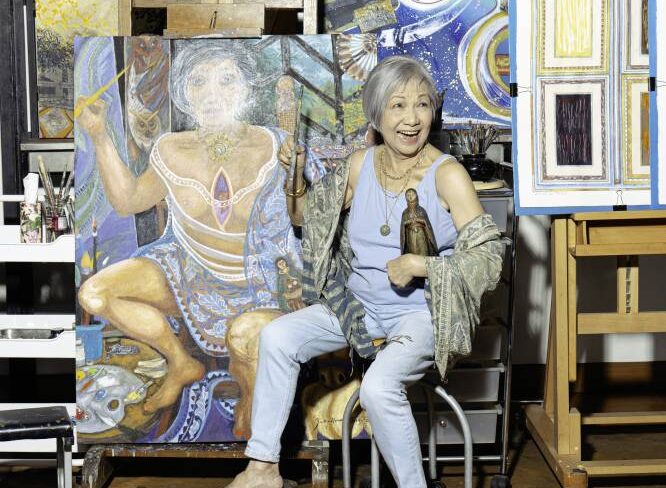

At the center of her studio today is a nude self-portrait, bohemian as ever. She paints one every ten years. In this edition, she depicts herself with sleek, silver hair, chest opened to reveal a Sacred Heart. At her feet is a rocking horse, gifted by her father when she was four and returned to her decades later by her grandmother.

“The background of these self-portraits is always my studio, whatever studio I’m in,” she notes.

But it’s her abstractions that are my favorite. Bold and imaginative, these canvases capture the same persistence and spirit that continues to define her as a cosmopolitan and lighthearted sophisticate.

Today, Zaballero is again in the spotlight with “Phyllis Zaballero: Landscapes of the Mind” at the National Museum of Fine Arts. The exhibition revisits her early abstractions, the same works that earned her the CCP Thirteen Artists Award and established her as a distinguished force in Philippine art.

These paintings, intense fields of color and form, stand in contrast to her later domestic tables and panoramic windows, but the throughline remains with her persistence to see differently and reframe the ordinary.

A space of persistence

Zaballero’s studio reflects a cultivated spirit in a space filled with art and objects that spark conversations across time. “Being an artist, I am very conscious of my surroundings, because it’s how I live, it’s what I smell, what I touch, what I see, that inspires me. It’s part of my life.”

While she is worldly in geography and her experiences, it shows too in her sensibility, as she is forever collecting, documenting, reframing, and conversing with the world through objects.

I’ve known Tita Phyllis since I was a little girl. Ever-chatty, I’ve seen listeners sit, mesmerized by her stories, myself included. And much like her paintings, her words have a painterly quality of their own, painting pictures in the mind.

Her studio, with its archives, stones, moving racks, and portraits, records a life on canvas, as well as the very architecture of her days. Distinguished yet unpretentious, Zaballero demonstrates that inspiration does not necessarily come from chasing novelty, but from persistence, memory, and a deep regard for the world.