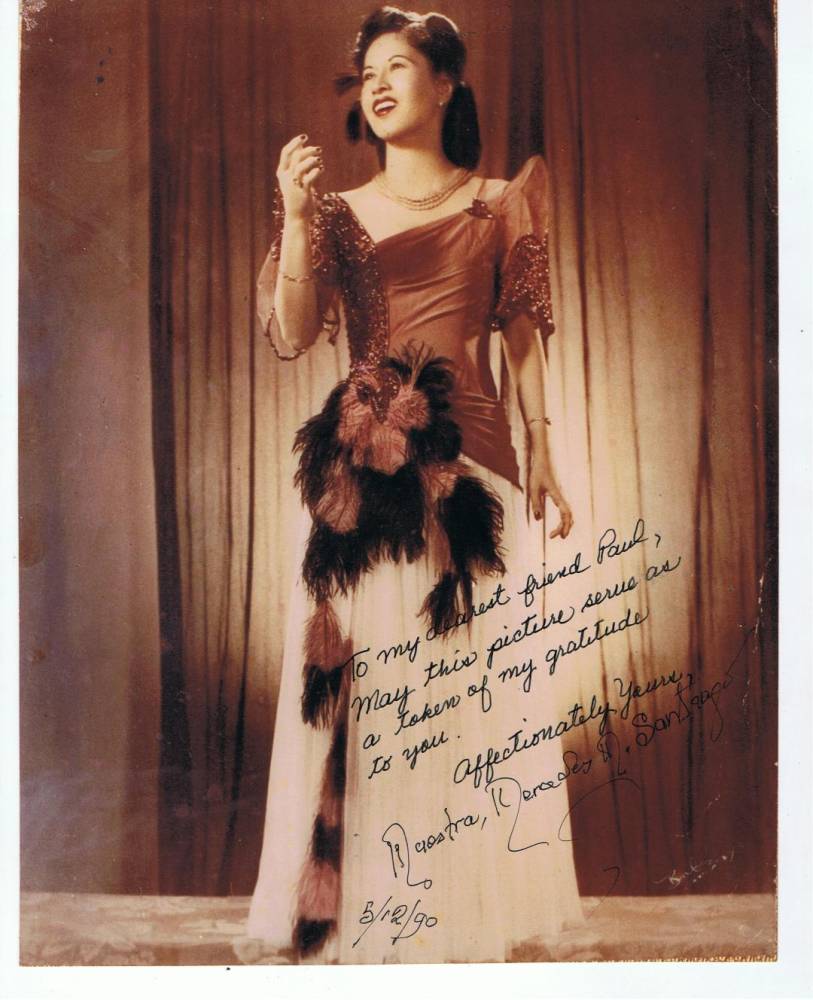

The forbidden love of the soprano and the tenor on Maceda Street

For many years, the house at 1081 Maceda St. in Sampaloc, Manila was where voice students went for lessons. In a small studio in this two-room apartment, the maestra received her students, taught vocalizations and good singing. The studio had an upright piano, a portable cassette recorder, and blown-up photos of students in voice recitals.

The place was also bursting with opera scores: “The Barber of Seville,” “Rigoletto,” “La Traviata,” “Madama Butterfly,” among others. On the ground floor was a huge painting of the maestra as Lucia in Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor.” She was, after all, the first Filipino soprano to sing the part and one of the first to sing Verdi’s “Traviata.”

There were two beds in another room that she used to share with a young tenor she had met at the peak of her “Traviata” and “Lucia” days.

Every time I visited them, I’d be treated to long listening sessions of their “Traviata,” “Lucia,” and “Madama Butterfly” recordings between bottles of beer.

As far as my ears were concerned, the soprano had nothing to fear from Lily Pons, while the young tenor could be favorably compared with Giuseppe di Stefano, a favorite opera leading man of Maria Callas.

Cluelessly, I’d frequently request the tenor to do my favorite Italian song, Gastaldon’s “Musica Proibita” (Forbidden Music). That explains why the piece is frequently asked for as an encore number of tenor Arthur Espiritu in Manila and Iloilo.

Cluelessly again, I once asked another singer-friend: When were the maestra and the tenor married?

It turned out they were not husband and wife. The soprano had been long separated from her husband, and the tenor was just her student.

After their paths crossed, the tenor, Aristeo Velasco, left his wife to live with the soprano, Mercedes Matias Santiago.

Scandal

In the ’50s, that was quite a scandal, and the repercussions were forthcoming. The soprano lost her teaching position in a famous music school and ended up teaching in her modest studio.

But her list of students nonetheless was distinguished. It included Conchita Gaston, Dalisay Aldaba, Remedios Bosch Jimenez (Baby Arenas’ mother), Catalina Zandueta, and, of course, the young tenor who became her lover. Among her other voice students were former first ladies Imelda R. Marcos and Aurora Quezon.

During their prime, the lovers were unfazed in the face of public ostracism. In the name of love, they lived together to the very end.

When Velasco died in the late ’90s ahead of Santiago, I was surprised to see her talking with the tenor’s ex-wife.

They are not enemies? I asked the maestra’s maid. When I turned to Santiago, she told me calmly, “Paul, we have forgiven each other a long time ago. We have shared the same man, and we both got our share of love. There is no reason to harbor ill feelings.”

The tenor’s niece and nephew were at the wake. They were no other than actress Sharmaine Arnaiz and actor Patrick Garcia.

When Santiago died in 2003, her wake was deluged with flowers from former pupils and friends who were silent witnesses to her love affair with the tenor.

The relationship was common knowledge in Manila music circles. The close kin apparently relegated this to the past. The close kin who read my story published in 2004 said they loved it.

Opera-loving family

Santiago was born March 4, 1910, one of two daughters of Juan Matias of Ligao, Albay, and Rosario Regalado of Cavite City.

This opera-loving family frequented the Manila Grand Opera House and the Manila Metropolitan Theater. She was the third Filipino diva, after Isang Tapales and Jovita Fuentes, to leave the country for further studies abroad. Tapales debuted as Madama Butterfly at Teatro Donizetti in Bergamo, while Fuentes debuted in Piacenza’s Teatro Municipale.

Santiago followed suit much later as Gilda in Verdi’s “Rigoletto” in Turin’s Teatro Comunale, followed by a matinee performance as Rosina in “Barber of Seville” in Milan’s Teatro Lirico.

For the record, she was the first and last Filipino to sing for the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini at the Palazzo where Italy’s top artists honored Il Duce.

President Manuel Quezon sent Santiago a bouquet measuring 7 feet tall with this inscription: “Ruisenor de Filipinas (Nightingale of the Philippines).”

In the ’30s and ‘40s, the soprano was the no. 1 interpreter of “Lucia di Lammermoor” and “La Traviata,” among others. In one performance as Anina in Bellini’s “La Sonnambula,” then President Quezon was present and sent her that tall bouquet.

Velasco was born in 1922 in Calauag, Quezon, likewise to an opera-loving family. His father, Pedro Velasco, was a doctor who loved music, while his mother, Dolores Pronstroller, was of German-Spanish descent. She took voice lessons and loved listening to a Victrola gramophone playing records of Italian singers like Amelita Gulli-Curci, Tita Ruffo, and Enrico Caruso.

When the tenor was about 6, the family moved to Manila and lived behind the Manila Grand Opera House, where he heard his first live opera. It is possible that the Velasco family had watched Santiago’s rendition of “La Sonnambula,” which was marred by a long brownout so that it ended at 3 a.m., but the audience stayed put.

A doting grandmother, Carmen Tronqued Pronstroller, took young Velasco to regular nights at the opera. He later realized that he could sing. He won radio amateur singing contests and became a regular fixture in such shows as “The Listerine Hour” and Colgate Palmolive shows. He soon had a sizable following when he started singing regularly in radio programs. In one program, Velasco was known as Johnny Velez singing with one Diana Tuy.

War years

The war years saw Velasco joining the Merchant Marines, where he was soon singing in a special program mounted by the Special Forces. Shortly before the war, he was lured to join bands performing in the hotel entertainment circuit. While singing for the band of Serafin Payawal at The Manila Hotel, he received a personal compliment from no less than President Quezon for the special way he interpreted Spanish songs.

Eventually, he and Santiago crossed paths. In one Manila production of “Lucia di Lammermoor,” Velasco played Lord Arthur Bucklaw while Santiago had the title role. The intensity of her mad scene must have left a mark in the young man’s heart. They fell in love, threw social caution to the winds, and lived together in the house on Maceda Street for many years until their deaths.

Why did the maestra’s marriage break up? She could only reflect on it gingerly. During our interview years ago, while listening to an old recording of “Traviata” arias, she told me that her husband had lost interest in her during those years when she was the opera toast of Manila. He hardly could be found during her opening nights. The husband was also listless that they had no children.

She said, “When I saw a doctor, I was told I couldn’t have a baby because my uterus was defective. That tore us apart even more.”

At that time, she was tall and beautiful, the tenor young and dashing.

The romance of tenor Velasco and soprano Santiago was ignited and intensified by their love of music. They didn’t seem to mind that polite society in the ’50s and the ’60s frowned on their relationship.

Their forbidden love was reflected in the beautiful lyrics of an aria from Tosca: “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore (I have lived for art and love).”

Interviewed by another friend, Santiago opened up about her life: “My life is something like the opera ‘Lucia de Lammermoor.’ It’s a little sad, a little tragic, and a little romantic.”

The above personalities in the arts are featured in the book, “Encounters in the Arts,” by Pablo Tariman. For inquiries, email artsnewsservice@gmail.com or call tel. no. (0906) 510-4270.