The musical odyssey of PPO founder Luis Valencia

When the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra (PPO) under Maestro Grzegorz Nowak performs at the Samsung Theater for Performing Arts in Makati City on Jan. 17, the national orchestra would have logged its 52nd year.

What many tend to overlook was that the pioneering musicians who comprised the first members of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) orchestra were trained and recruited by its founder, violinist and conductor Luis C. Valencia.

In 1932, Valencia earned a diploma from the University of the Philippines (UP) Conservatory of Music (now the UP College of Music).

In 1938, he became the first Filipino graduate of the Vienna State Academy of Music.

From his Valencia Academy of Music came the pioneers of the CCP orchestra, now known as the PPO. He retired from the CCP in 1980 and died a few years later.

I only know he conducted an orchestra that accompanied the celebrated American diva Beverly Sills at the Meralco Theater in 1969.

He conducted the CCP orchestra when it accompanied pianist Van Cliburn at the CCP and at the Araneta Coliseum. In 1973, he accompanied the legendary opera singers Renata Tebaldi and Franco Corelli.

The first time I saw him perform was in 1975, when the CCP orchestra accompanied Cecile Licad in an evening of three concertos.

Journey

Looking back, the musical odyssey of Valencia started in Aliaga, Nueva Ecija, where he was born.

Before I saw him perform with Licad in 1975, I was a frequent visitor at his Cubao residence, and on weekends, I would pass by for him at the PWU College of Music and proceed to Aliaga town, where he started telling me his story.

He remembered Francisco Medina, who used to teach in Shanghai and who, upon his retirement, settled down in Aliaga. It was in 1925 when a truck loaded with musical instruments arrived in the sleepy town. When Valencia saw them, he went wild with excitement.

Medina gave Valencia a few basic lessons. Shortly after, he was asked to conduct the band composed of his brothers, sisters, cousins, and other relatives. The first few minutes wielding a baton were exhilarating.

In 1936, when he decided to take up postgraduate studies, his journey took a new twist with a slow boat to Vienna. With just enough token money from his benefactors, the young Valencia boarded the ship President Wilson.

Being poor, he was booked in the steerage class, or third class in today’s parlance. One day, as they were passing Singapore, the ship captain dropped by his camarote (berth) and asked about his destination.

“Where are you going, young man?”

“To Vienna,” he replied.

“What for?”

“To pursue an advance course in music.”

“What do you play?”

“Violin, sir.”

“Do you have enough money?”

“No, sir.”

“Would you like to earn money for your schooling?”

Financial dilemma

Valencia was happy at a good opportunity. At that time, there was no standard entertainment aboard the ship.

The captain told him, “Play the violin for my passengers, and I’ll pass a hat around.”

The ship deck was an unlikely setting for another recital, but he acceded and earned $300.

It was the year made famous by the story of the Von Trapp Family Singers. It was the year Hitler’s war was rearing its ugly head all over Europe.

But Valencia’s dilemma at that time was more financial than political. His money could last him in Vienna only a year. All postgraduate students were required to stay for at least two years.

His solution to his problem: finish the two-year course in one year.

His case was brought to the attention of the president of the academy, and his request was considered. He could try to finish the two-year course in one year provided he passed the written and oral examinations of the jury.

After a year, he passed the course with a grade of “Excellent.”

Vienna meant many things to Valencia.

He met the great Toscanini, whose rehearsals he used to attend. He also met the German conductor Wilhelm Furt Wangler, whom he considered almost as good, if not better, than Toscanini.

Meanwhile, the shadow of Hitler was looming all over Vienna. Valencia’s friends advised him to leave the city at once.

From Vienna, he took the first passage to Trieste, a port between Italy and Yugoslavia. He proceeded to Hong Kong, taking the ship Conte Rosso. In Hong Kong a few days later, the newspapers screamed: “Hitler Grabs Vienna!”

Serendipity

He remembered the ship Conte Rosso because of a Hungarian passenger named Mr. Hollach, who enjoyed listening to him while he played the violin in his camarote. Stranded for two weeks in Hong Kong for lack of available ships back to the Philippines, he bumped into Mr. Hollach, who immediately sensed he had a problem.

Mr. Hollach dipped his hand into his pocket and handed him $500 to pay for his hotel bills and for his ship, which would sail for the last time on its way back to Hong Kong.

When he arrived in Manila, Doña Aurora Quezon told him to report to the UP Conservatory of Music for a teaching job. Realizing the dearth of musicians in the country, he decided to devote his time to training young people, all of whom would make up the members of the Filipino Youth Symphony Orchestra.

Earlier, he made an auspicious debut as a violinist with three concertos with the Manila Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Dr. Alexander Lippay. The concert fare consisted of Bach’s “Concerto in E Major,” Brahms’ “Concerto in D Major,” and Paganini’s “Concerto in D Major.”

His conducting debut was at the original Metropolitan Theater during the Japanese Occupation, with the New Philippines Symphony Orchestra. He tackled Mozart’s “Symphony in G Minor” and Tchaikovsky’s “Concerto No. 1 in B Flat.”

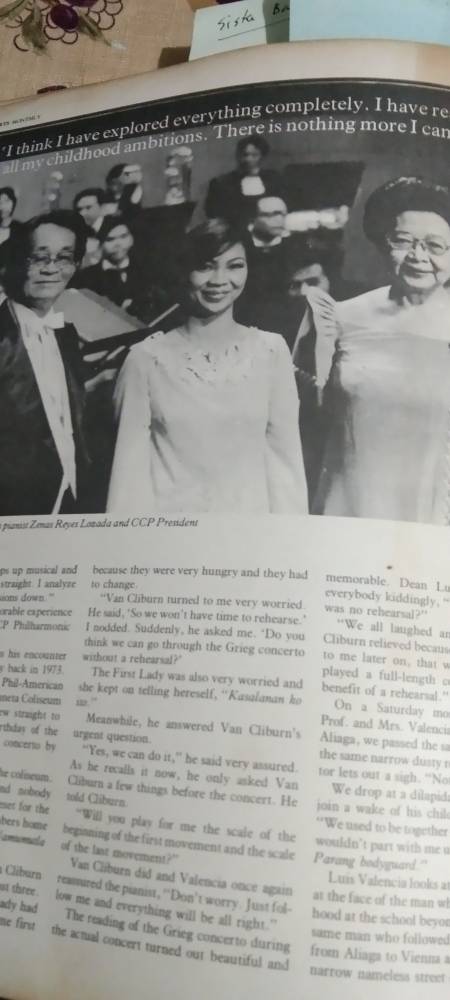

His most memorable experience as a conductor of the CCP Philharmonic Orchestra was his encounter with pianist Van Cliburn in 1973. The main fare was Grieg’s “A Minor Concerto” at a Philippine-American Friendship Concert at the Araneta Coliseum.

The concert was at 5 p.m. Cliburn and Imelda Marcos arrived a little past 3. “Where is the orchestra?” she asked. He said he had sent them home first because they were very hungry and had to change.

“Cliburn turned to me, very worried. He said, ‘So we won’t have time to rehearse?’” Valencia nodded.

“Van Cliburn asked me, ‘Do you think we can go through the Grieg concerto without a rehearsal?’”

Valencia assured Cliburn, “Yes, we can do it.”

He only asked Cliburn a few things before the concert. He told Cliburn, “Will you play for me the scale of the beginning of the first movement and the scale of the last movement?”

Cliburn did, and Valencia reassured the pianist, “Don’t worry. Just follow me and everything will be all right.”

The reading of the Grieg concerto during the actual concert turned out to be beautiful and memorable. Dean Lucrecia Kasilag told everybody kiddingly, “Was it because there was no rehearsal?”

Valencia said, “We all laughed, and I turned to Cliburn relieved because, as he would confide to me later on, that was the first time he played a full-length concerto without the benefit of a rehearsal.”

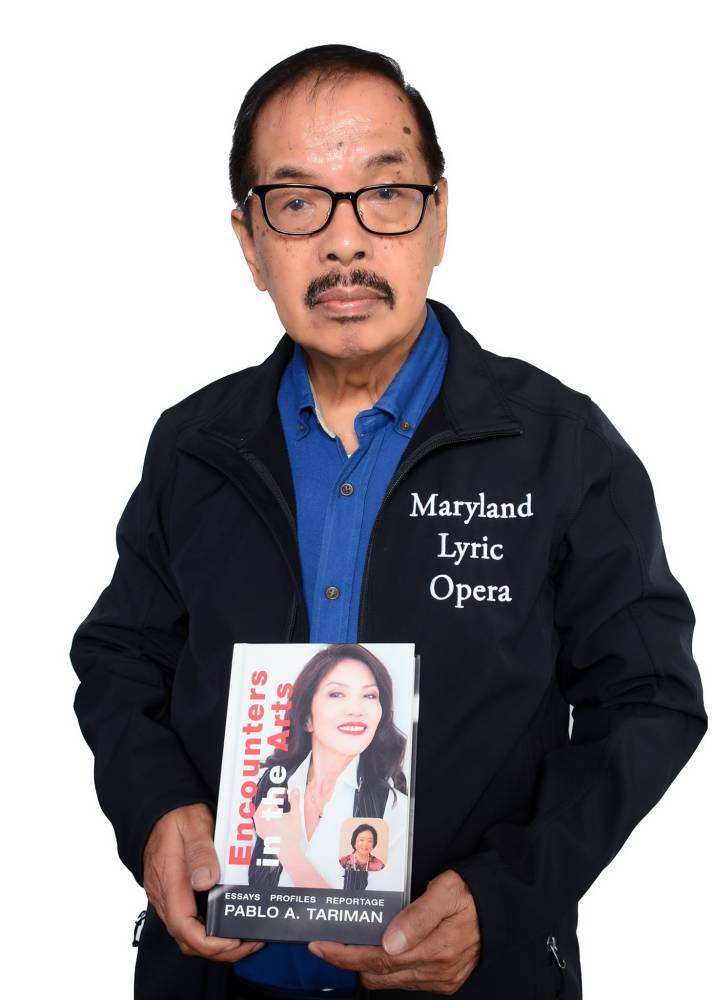

This profile of Maestro Luis C. Valencia is reprinted from Pablo Tariman’s second book, “Encounters in the Arts.” For inquiries, call tel. no. (0906) 510-4270 or email artsnewsservice@gmail.com.