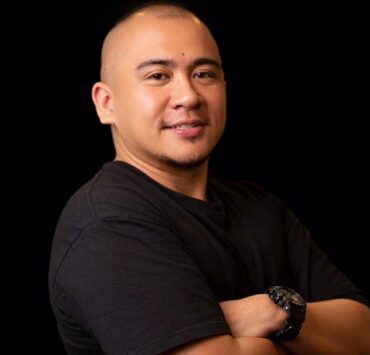

The printmaker from Sitio Botiwtiw

Leonard Aguinaldo literally lives the best of both worlds. His home studio in Benguet is on a hill overlooking Baguio on one side and Trinidad Valley on the other. How can he not be motivated to work each day with views like that?

He has come a long way from selling his handmade cards in the 1990s in bazaars at Brent School or on the Session Road sidewalk during Panagbenga season. When he won the Philip Morris Grand Prize in the Asean Art Awards in 2004, he had enough downpayment to pay for land and a big room on Sitio Botiwtiw in Ambiong, La Trinidad, Benguet, where he and wife Christina moved with their children.

The room grew from there, with partitions being knocked down to make way for a more spacious studio that can also house Leonard’s Inima Press, “inima” meaning “hand press” in the Iluko language. The large press, which can even accommodate a 4-foot by 8-foot piece of carved plywood, is interesting in its gewgaws. Inspired by the Ifugao ceremonial bench hagabi, the press was assembled by the multimedia artist himself. The wheel he fabricated, but the gear is from a recycled coffee roaster. Another printing machine, much smaller, has signage recycled from a hotel.

Leonard works from late evening to early morning, but there are no eyebags to show for them. He works on themes related to Cordillera life ways, and tweaks these to give them a contemporary, sometimes humorous, edge. These days find him carving on plywood the background for a series of wall-size prints that will be shown at the Ateneo Art Gallery, at the Arete Building on the Katipunan campus, from April to July this year. His works will be on exhibit with those of other Baguio artists.

Spirit house

Overseeing his print studio is a triangular spirit house he carved and colored inside and out to commemorate his parents and their story. His mother Petra journeyed from Candon, Ilocos Sur, then met his father Bartolome Sr. in Manzanilla, Baguio, where he was working as a house help. They married and settled in the city.

The family history is repeated in a life-size red and white print on the living-dining room walls. Christina said having the walls and posts covered with her husband’s prints is cheaper than painting them, and a simpler process, too. The prints are done on any paper like newsprint, and glued to the walls. They look better than commercial wallpaper, plus they tell the story of the Aguinaldo family.

On the walls by the paminggalan or dish rack are more prints, then the eyes travel towards a row of hanging wooden spoons, each stem carved with a name: Jose Zane, Roxy, Balitok, Pablo, Santiago, and Enzo. On the bowl part of the spoon are the faces of dogs. Leonard explained that these are remembrances of the first generation of dogs they had when they had just moved to their Botiwtiw house. Only two of those dogs have survived. At that time, he was doing hand pressing for his prints, so it felt as though those pets were part of his artistic process.

Today, the family has eight dogs of different breeds. One has the unique name of Nepnep to mean the monsoon season in the uplands, when the family received the dog.

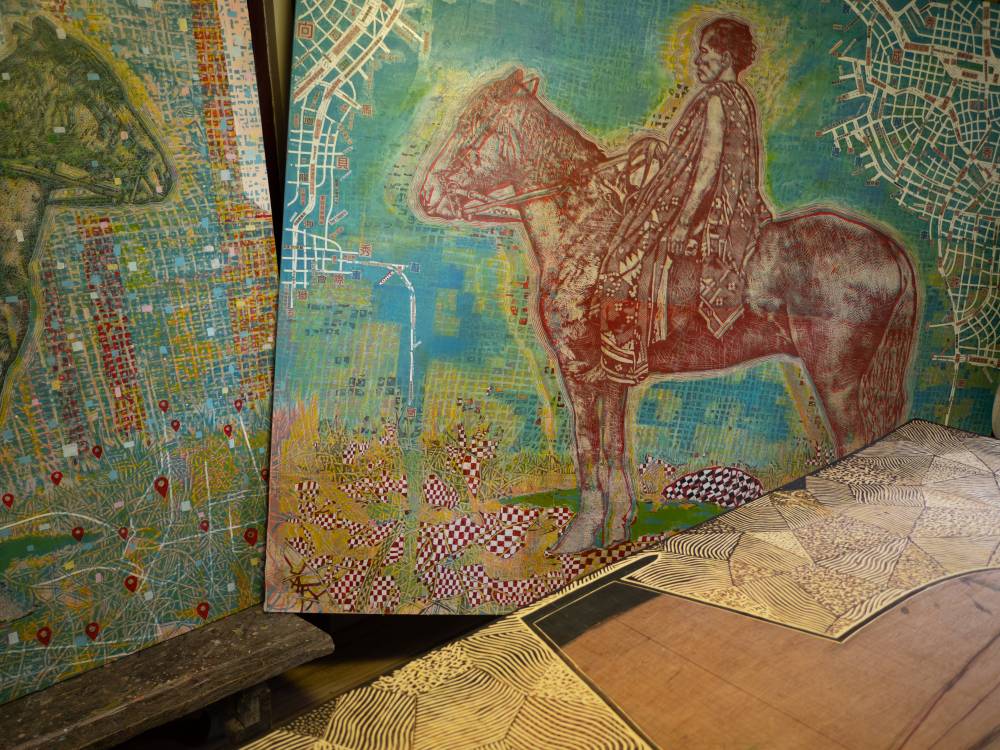

Leonard developed an allergy to rubbercuts, especially when he was making huge ones, so he switched to woodcuts since plywood was cheaper and readily available. Among his latest works are “Disappearing Lands” with an indigenous man on horseback. These will be exhibited at the Alt (for Alternative) Art Fair in August.

Tribute exhibit

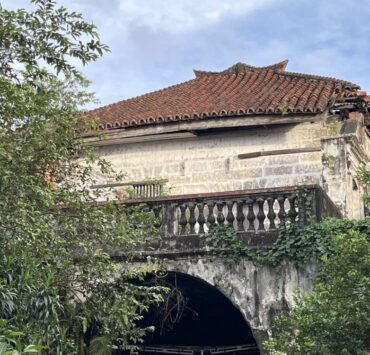

Currently, Leonard is among the artists participating in the tribute exhibit for the late Rene Aquitania, “Set in Stone: Re-imagining the Sagada Dap-ay” at the Victor Oteyza Community Art Space or VOCAS, La Azotea Building, Session Road, Baguio.

The Aguinaldo children have gone down different paths, with the eldest Sky working at a government media station, the second Mandala studying radiology at St. Louis University, and Karayan dabbling in digital art at the Open University.

Christina said what drew her to Leonard were “his kindness and his being funny. He’s not too serious. If something challenges him, he doesn’t take it to heart. He faces it.” Now that she is done with her school fetcher duties, she helps market the bags, t-shirts and cards that carry the Aguinaldo imprints.

Apart from this, she has discovered the delights of fabric art, sewing designs on or around her husband’s silkscreen prints. She is helping her sister Kat Palasi, who’s into natural dyeing and embroidery, by organizing the neighborhood women to work on Kat’s designs in their respective houses. They gather serviceable but secondhand denim jackets from the ukay-ukay stores, then upcyle these with botanical and other designs. If they’re lucky, they stumble upon good Japanese-made denims.

That makes the generally quiet Aguinaldo home a magnet of sorts for clients, friends, art students and curiosity seekers drawn to the bluff where, on one hand, Baguio sprawls below and on the other, La Trinidad. Some people are just so lucky, but Leonard would be the first to say it wasn’t pure luck alone that brought him to this point on a hill.