The Skims face wrap is designed to make people feel more insecure

The constant bombardment of content on the internet is leaving us with growing sentiments of hopelessness and futility. You are being presented with a lifestyle that feeds your dissatisfaction every day. But how can you resist the vacuum of social media when you’re living in a digitized society?

Maybe the key is not a complete resistance to content you can’t avoid, but a vigilance to how images and texts are used to contort your values.

The latest Skims innovation is a prime example. It’s important to process how you feel when you find yourself being advertised shapewear for the face. Otherwise you end up passively accepting harmful messaging. Does it make you feel numb? Disempowered? Confused? Our greatest weapon against social conditioning is feeling. The more attuned we are to our emotions, the more capable we are of making active decisions.

The Skims controversy

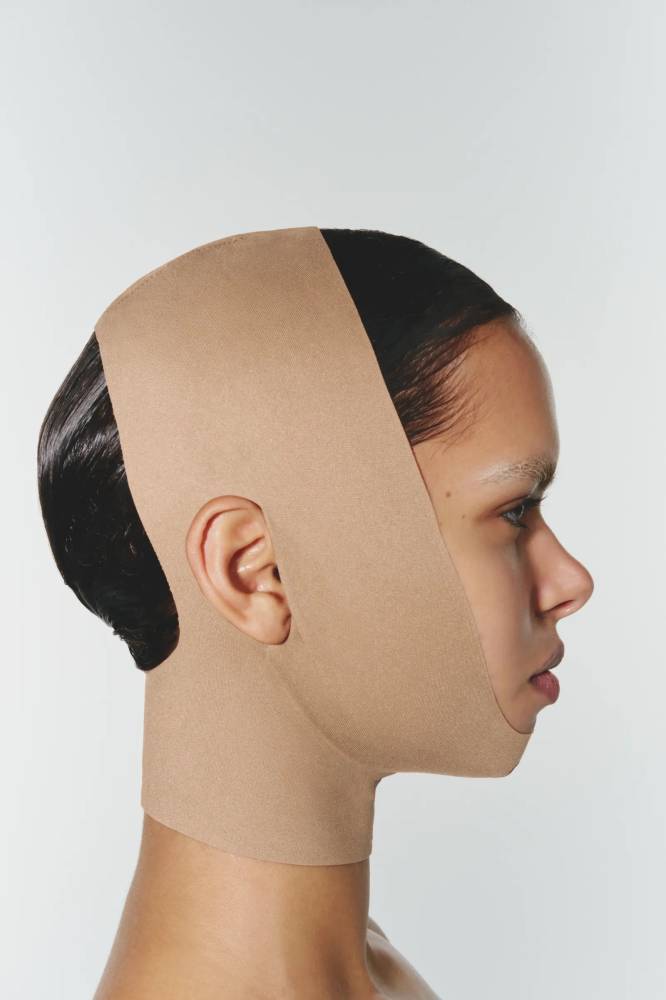

The Skims seamless sculpt face wrap is the latest product to spark controversy on the internet—following Sydney Sweeney’s American Eagle ad campaign. The product, which is similar in appearance to a post-surgical bandage, “boasts [Skims’] signature sculpting fabric and features collagen yarns for ultra-soft jaw support.”

Its description on the Skims website is notably cursory and unclear. What does jaw support actually mean? What are its effects on your facial structure? What is the product’s purpose? The product is as questionable as its price tag— a whopping P3,000 for a sliver of fabric supposedly infused with collagen.

When I first saw the product, my immediate reaction was that of disgust. Not just because a little investigation proves that it is utterly useless, but because the garment itself is creepy. In an Instagram post, Anthony Hopkins donned the wrap in a skit in which he channeled Hannibal Lecter. Michelle Elman, an author and body positive activist, likened it to something you may find in Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

Social media users were quick to generate the discourse surrounding the product. To an audience of over 100,000 followers on Instagram, Brett Staniland says, “What I find interesting is the chokehold Kim [Kardashian] still seems to have on people, especially considering most of her products subliminally message to people that their bodies, and now their faces, are undesirable. And [they’re] not just preying on people’s insecurities, but actively creating them.”

Another social media post by author Tova Leigh writes, “Kim Kardashian didn’t invent toxic beauty standards. But she sure as hell profits from them. This is what it looks like when insecurity becomes a business model.”

This is an age-old story. The entire Kardashian empire was built on a false ideal. The Kylie lip kits that claimed to naturally plump Kylie Jenner’s lips blew up in sales before Jenner disclosed her plastic surgery. Now it’s a billion dollar company. While we could be tempted to frame this narrative as that of female empowerment and a testament to the girl boss, its effect on young girls may have actually been to diminish their autonomy and even manipulate the appearance of free choice.

How can anyone be truly free to choose what they desire for themselves if their notion of the ideal woman has been commercially engineered to make them feel bad about themselves?

How do we resist?

In Jia Tolentino’s 2019 essay, “Always Be Optimizing,” Tolentino describes the “ideal woman” as a woman loyal to the systems that oppress her. She describes a woman of a youthful appearance, glossy hair, and a photogenic quality. A woman who subconsciously believes that their principle purpose is to be looked at and admired. She likely is constantly in athleisure or otherwise luxuriating on the beach.

This description is not to implicate any particular woman, but to exemplify an image we have been made to aspire to. Our notion of the ideal woman, is of course, a woman desirable to men. A woman who endorses products that have an insidious way of chipping at our autonomy and self esteem, while simultaneously existing within the terms of choice and empowerment.

“Can you see this woman yet?” Tolentino writes, “She looks like an Instagram—which is to say, an ordinary woman reproducing the lessons of the marketplace, which is how an ordinary woman evolves into an ideal. The process requires maximal obedience on the part of the woman in question, and—ideally—her genuine enthusiasm, too.”

In becoming the “ideal woman,” we commodify ourselves. We make ourselves available to the market that exploits us, so much so that even sleep, an essential component of our wellness as human beings, is now a mechanism of productivity beyond caring for our health.

The Skims face wraps, marketed as a “must-have addition to your nightly routine,” infiltrates our moments of rest. What do we do to combat this commercial imposition? We simply sleep without it. We allow ourselves to breathe, to close our eyes for a few hours, and imagine waking up to a society whose demands are kinder and more just. We rest only to wake up disillusioned, but not, at the very least, disenfranchised.