The spy who loved Luna

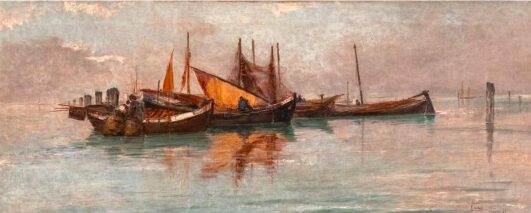

In the flickering glow of Venetian moonlight, a fishing boat glides silently over a still lagoon. The sails, caught in mid-billow, whisper of labor, movement, and mystery. This is “Claro de Luna en la Laguna de Venecia”—a rare seascape painted in 1887 by Filipino master Juan Luna.

Soon, it will be offered to the world once more, not in a dim gallery of European aristocracy, but under the spotlight of León Gallery’s “Spectacular Mid-Year Auction” on June 7.

Yet the painting’s journey—from Luna’s brush to the noble halls of Spanish power, and finally to the vaults of a real-life American spy turned countess—is as fascinating as the twilight scene it portrays.

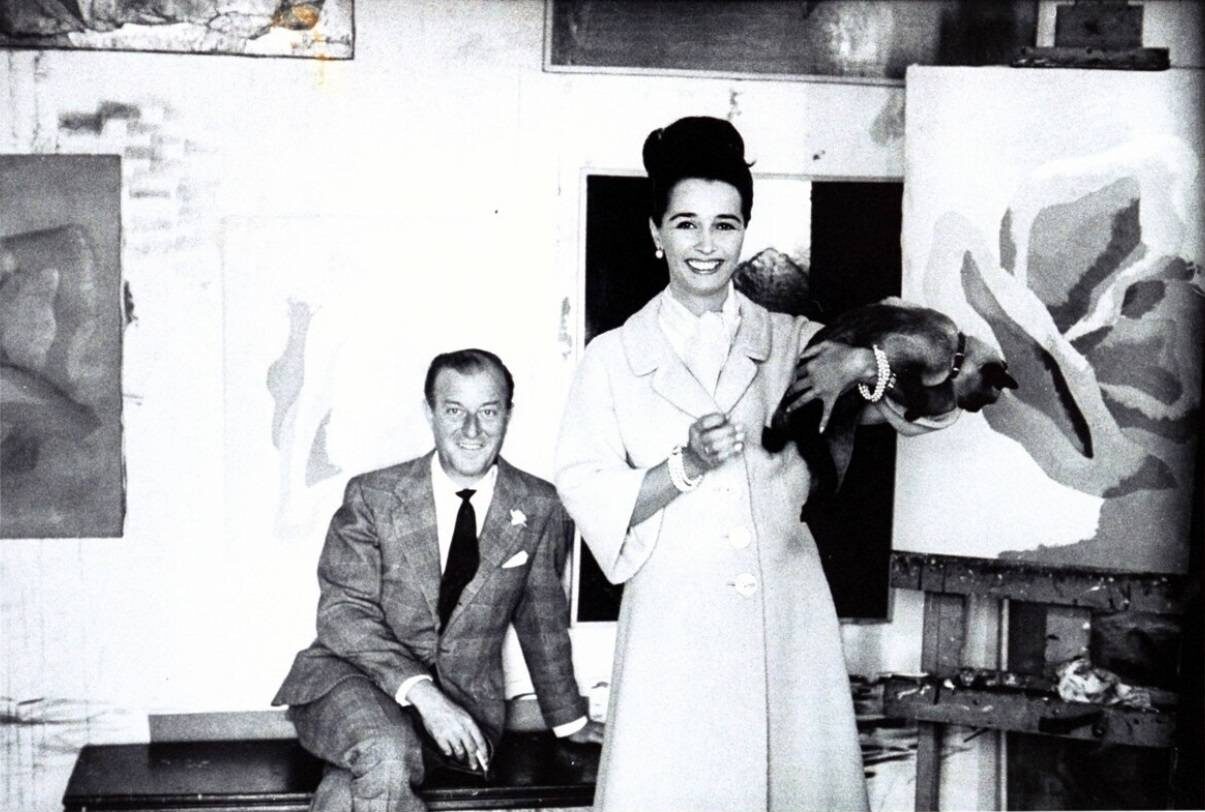

Her name was Aline Griffith. Born in suburban New York, she was recruited during World War II into the Office of Strategic Services—the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. Elegant, calculating, and possessed of fluent Spanish, she operated in Madrid under the alias “Alicia Dreyfus,” gathering intelligence among Nazi sympathizers while mingling with Europe’s glittering elite. Then, in a twist worthy of a romance novel, she married into that elite.

In 1947, Griffith wed Luis de Figueroa y Pérez de Guzmán el Bueno, Conde de Quintanilla and later Conde de Romanones, heir to one of Spain’s most powerful noble houses. Her new home? A labyrinth of castles filled with treasures: Velázquez portraits, Goyas, medieval tapestries—and tucked among them, a moonlit seascape by a Filipino artist named Juan Luna.

Griffith, now the Countess of Romanones, would later claim in her bestselling memoirs—“The Spy Wore Red,” “The Spy Went Dancing,” and “The Spy Wore Silk”—that she remained active in intelligence circles even after donning her tiara. Critics dismissed some of her tales as fantasy, but her books nevertheless catapulted her to fame.

One story she didn’t tell, however, was how Luna’s painting came to be in her family’s possession.

For that, we turn back the pages to the late 19th century.

A Filipino in the corridors of power

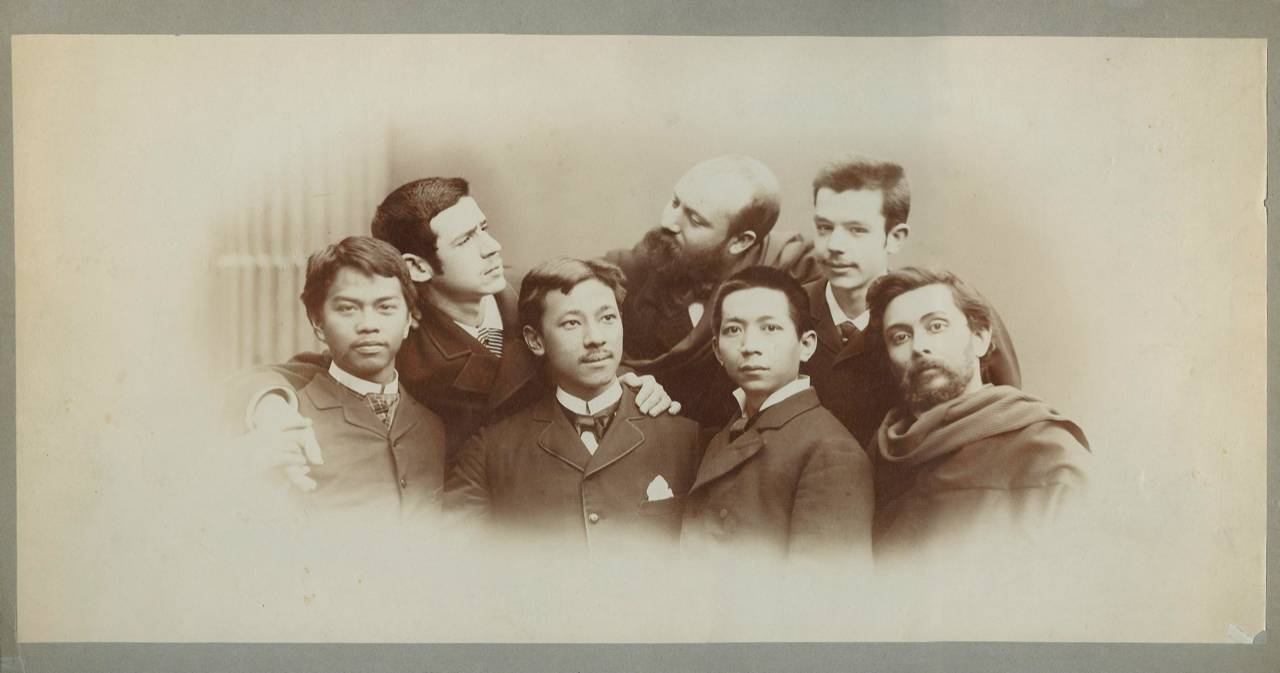

Luna was not merely an artist—he was a phenomenon. Born in the Philippines in 1857, he studied at the Escuela de Dibujo y Pintura in Manila before voyaging to Europe, first as a trained navigator and later as an aspiring painter. After rigorous academic training in Madrid under Federico de Madrazo at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Luna made his way to Rome, where his artistry—and his connections—flourished.

His masterpiece “Spoliarium” won the gold medal at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1884, catapulting him to international acclaim. But more than medals, Luna secured the favor of Spain’s intellectual and political elite. In the bohemian Roman salons of Via Margutta, he rubbed shoulders with the Benlliure brothers, Mateo Silvela, and a young law student named Álvaro de Figueroa y Torres.

That student would become the first Conde de Romanones, a future prime minister of Spain and long-serving director of the Royal Academy where Luna had once studied. Their friendship transcended art. Romanones would later recall, with fondness, “lively Roman days with Luna, Mariano [Benlliure], José, and Mateo.”

It was during this gilded time that Luna painted “Claro de Luna en la Laguna de Venecia”—and sold it directly to his old friend, the future count.

Masterwork between two worlds

At first glance, “Claro de Luna en la Laguna de Venecia” seems like a departure for Luna, who is best known for his epic historical canvases like “Spoliarium” or the allegorical “España y Filipinas.” But this luminous seascape offers a quieter, more intimate window into Luna’s artistic soul.

Painted in 1887, the canvas portrays traditional bragagnas—Venetian fishing boats—gliding through moonlit waters. But beyond its shimmering surface lies a metaphorical depth. According to Lisa Guerrero Nakpil, the painting captures “a man on the cusp of glory,” fresh from his triumph in “Spoliarium,” and navigating the turbulent waters of fame, politics, and personal destiny.

Indeed, Luna’s connection to the sea was more than symbolic. At age 12, he enrolled in Manila’s Escuela Náutica, sailing across Asia and absorbing the maritime rhythms of empire and labor. His maritime upbringing informed his understanding of light, movement, and working-class dignity. Unlike Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, whose seascapes romanticized the waves, Luna’s “Claro de Luna” is grounded in realism. The moon’s reflection glimmers not just on water—but on toil.

Lost, then found

From Luna’s Roman studio, the painting entered the collection of the first Conde de Romanones and remained with the family for over a century—quietly surviving revolutions, two World Wars, and a glamorous American countess’ spy games. When Griffith became Countess of Romanones, she inherited not only titles and castles but also the legacy of her husband’s artistic patronage.

Though she never publicly mentioned Luna in her books, family records and auction provenance confirm that “Claro de Luna” remained among her collection until her passing in 2017. Now, with her estate finally unspooling its secrets, the painting returns to public view.

Jaime Ponce de León, Leon Gallery’s founder, describes the painting as a “capsule of Luna’s golden years,” not just for its artistry but for its provenance. “It represents not only his talent, but his incredible ascent into the aristocratic and political circles of Europe. It’s a historical gem.”

National treasure

The sale of “Claro de Luna” arrives at a moment of growing international recognition for Luna. Long eclipsed by colonial erasure in Spain, Luna’s legacy is being reevaluated as part of a global Filipino diaspora narrative—one in which art, diplomacy, and ambition intersect.

This painting is more than a moonlit lagoon—it is a testament to Luna’s mastery and mobility, to a Filipino artist who once commanded the attention of European nobility, and to a countess who may or may not have whispered secrets into palace corridors.

If paintings could talk, “Claro de Luna” would speak not just of Venice, but of empires, revolutions, and the long journey home.

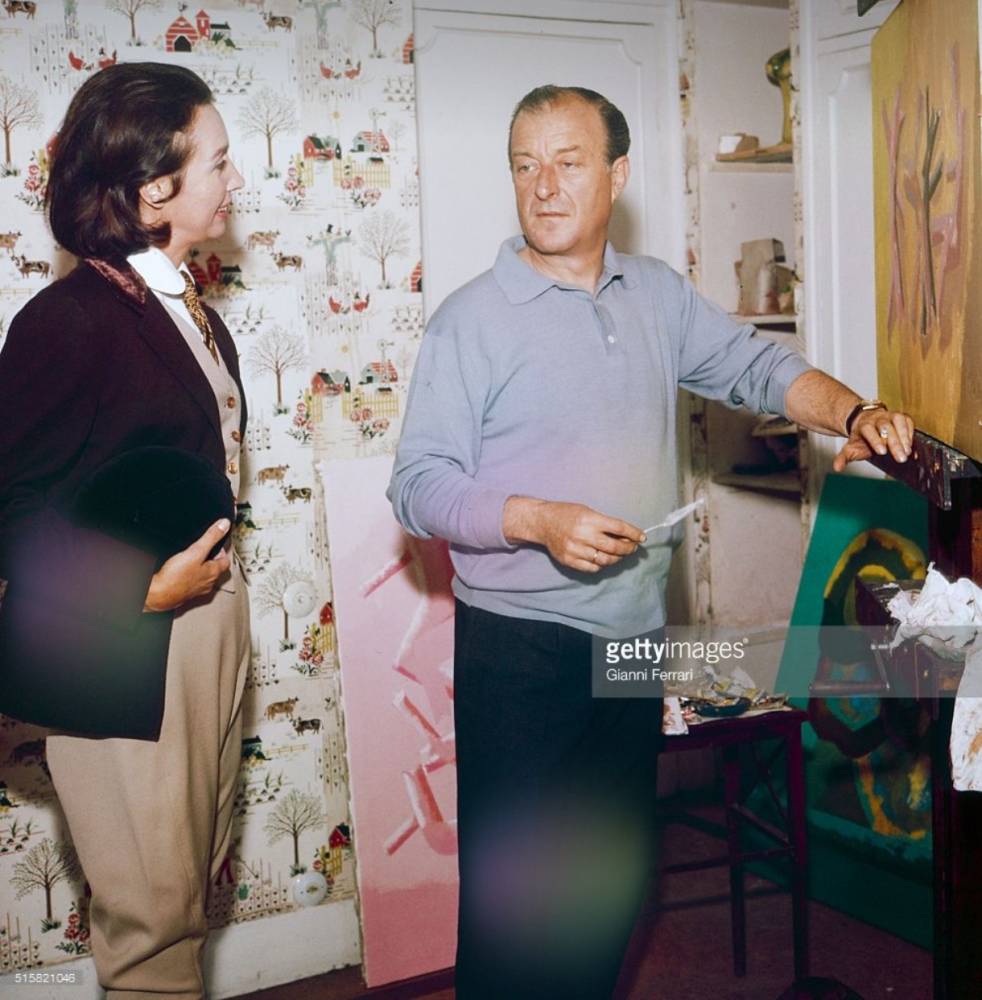

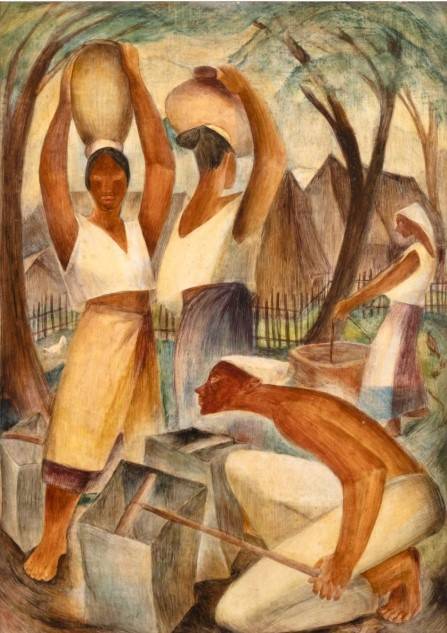

Marking its 15th anniversary, León Gallery’s “Spectacular Mid-Year Auction” will showcase other rare and museum-worthy masterpieces, such as Anita Magsaysay-Ho’s “Water Carriers” (1947), a luminous egg tempera gem from her Cranbrook years, and Vicente Manansala’s “From the Market” (1975), featuring intimate portraits of himself and wife Hilda.

Also headlining the sale is H.R. Ocampo’s modernist breakthrough “Miners” (1952) and Fernando Amorsolo’s epic “The Burning of Manila,” once owned by Don Enrique Zóbel.

Complementing the fine art are historic treasures from Ambeth Ocampo and pieces from the esteemed Belo-Kho collection. A landmark event not to be missed.