The time of monsters

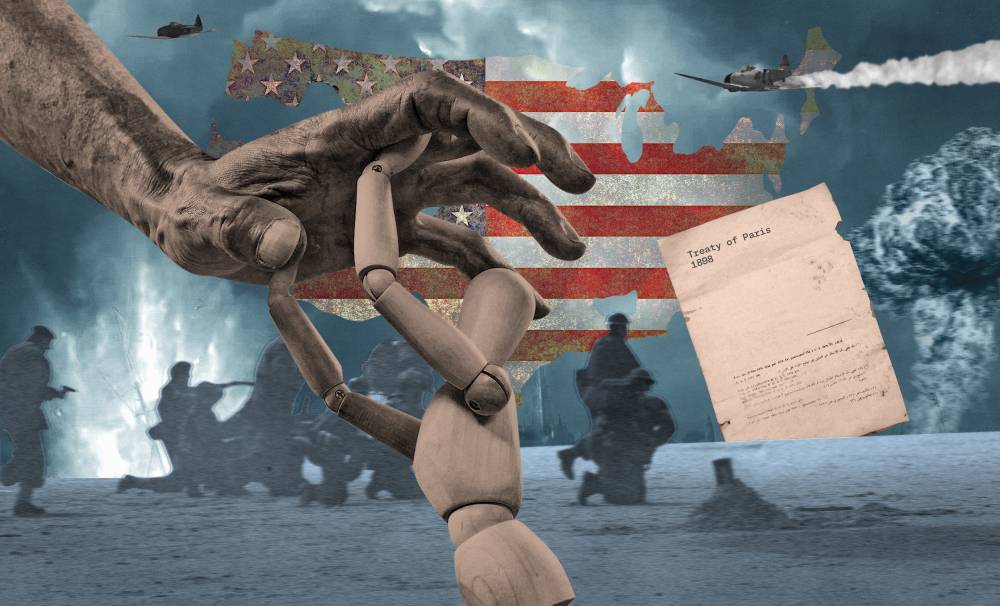

Exactly 127 years ago, on Dec. 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed, officially ending the Spanish-American War that once saw an all-powerful empire feebly chugging along Manila Bay on its antiquated warships formally cede the islands of the Philippines, Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the brash new imperialist kids on the block.

Ironically, just six months before, the Philippines, under General Emilio Aguinaldo, declared independence from Spain and raised the flag of the new Philippine Republic in Kawit, Cavite, with the full knowledge—but not the recognition—of the Americans, only to be hoodwinked. The Philippine-American War, which broke out in 1899, was inevitable.

From one colonizer to the next

As historian and academic Vicente Rafael noted in his paper “Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines 1565-1946,” “Having just overthrown one colonial master, they were not ready to suffer the pretensions of another one.” Moreover, the US had just paid Spain $20 million for the “title” to the Philippines—so of course, it wanted a return on its investment, and there were 7,107 islands whose lush natural resources were ripe for exploitation.

Three decades later, the Italian Marxist philosopher and political theorist Antonio Gramsci wrote these famous words in his “Prison Notebooks,” “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born. Now is the time of monsters.”

Gramsci may have been referring to the encroaching fascism in Europe between the two World Wars, yet his words could well be applied to the anti-colonial revolutionary fervor that swept the colonies of Spain throughout South America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific, not to mention the political transformations taking place in Europe in the second half of the 19th century.

It was this same fervor that no doubt led Aguinaldo and his men to believe at first that the Filipinos and Americans were allies in their fight, not just against an imperial power breathing its last, but the notion of empire—the old world itself—towards a new world.

In the revolutionaries’ eyes, this new world would worship no king but commit instead to a republic founded on democracy, justice, and egalitarianism.

Enter the monster

Because colonizers gonna colonize, the United States of America could not restrain its own global expansionist ambitions. Nor could it suppress its inherent racism. And the equally racist OG colonizer, the Spanish, could not countenance having to surrender to the brown people they had subjugated for 333 years.

By this time, several thousand Spaniards were being held in captivity in Intramuros by Filipino troops. To spare the Spanish the ignominy of defeat at the hands of the “natives,” the highest-ranking representatives of both nations in the Philippines, the American commodore George Dewey and the Spanish general Fermin Jaudanes, colluded, in a deal brokered by yet another European colonizer, the Belgian consul Edouard André, to stage a mock battle of Manila.

It was pure theatre, with negligible casualties on both sides. There were no encores, but at curtain call, the Spanish raised the white flag at 11:20 a.m. as planned, conveniently timed so that all the actors in this charade could break for lunch. How very civilized.

And as a coda, there was a 21-gun salute, courtesy of the British armored cruiser HMS Immortalité, in honor of the US flag now flying atop Fort Santiago.

America had positioned itself (as it would again in 1944 during WWII with MacArthur’s dramatic landing on the shores of Leyte to “liberate” the Filipinos from Japanese occupation, having deserted the very same people in 1941) as the Philippines’ savior, but Filipinos soon discovered that the Americans may have had better military equipment and a slicker public relations machine, but they were racist, white supremacist colonizers to the core.

And like all colonizers, their love language was violence disguised as civilization.

How the mighty will (eventually) fall

“Benevolent assimilation” is what then president William McKinley called it, while Theodore Roosevelt, previously governor of New York, then McKinley’s Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and later his vice-president, was more disparaging, bestowing such choice epithets upon Filipinos as “Tagala bandits,” “Malay bandits,” “Chinese half-breeds,” and “savages, barbarians, and wild and ignorant people.”

Recall that Roosevelt, who assumed the presidency upon McKinley’s assassination in 1901, agitated for the Spanish-American War and the annexation of the Philippines and Cuba. His was the evangelical belief in the “superior people theory” that positioned the United States as a world power. “The most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages,” he declared.

Unfortunately, monsters beget monsters. They live among us, in the puppet leaders of the client states the US props up across the Gulf states and the rest of West Asia, not to mention European countries whose governments may waver between conservative and leftist governments but in the end bow down to the Americans like the good vassals they are, for the sake of “Western civilization.” And oil. And gold.

I take comfort in the incontrovertible fact that all empires end. Rarely willingly, almost always violently.