The two sides of marine tourism in Bohol

Whatever happened to Balicasag Island?

As our boat sped through the clear turquoise waters, expectations were tempered but far from dim.

A zoomed-in photo taken from the plane the day before showed a number of boats lined up along the beach, a stark difference from when we practically had the island to ourselves back in 2006.

But it has been almost two decades since we took our advanced open water diving certification there (barely escaping the small island before Typhoon “Milenyo” hit only a few hours later), after all. Realistically speaking, more tourists would know about the island by now, especially those coming in from colder climes this time of the year.

Still, the waters surrounding Balicasag have been a marine sanctuary since 1985. And when we first went there, it was one of the most breathtaking underwater views we’d ever seen. The aquatic ecosystem was rich and vibrant, densely populated with colorful corals and an abundance of marine life. Even the night dive proved spectacular, despite the strong current that kept sweeping us away. The area has clearly been protected.

But we couldn’t hide our dismay as we approached the shore after the hour-long trip. There were so many tourist boats already there, ours had a hard time finding a parking spot. The serene scenery has now been replaced with a row of tiangge, rental shops, eateries, and covered designated dining areas abuzz with people and background music. We were escorted to sit on plastic chairs facing a small enclosed office as we awaited our turn in the water, it felt and looked like queuing for our driver’s license at the Land Transportation Office.

To be fair, the wait didn’t take too long. But the fact that there was even a holdup already clued us in on how populated the site has become (not that the density of the people milling about wasn’t a clear enough clue to begin with).

Occasional fish

And yet we took it as a good sign: The fact that people have to wait to get into the water—and are only allowed one hour tops to enjoy the underwater views—gave us the impression that the people in charge were restricting the number of snorkelers to avoid crowding the area. But when we finally got out into the open water, the designated snorkeling area was so packed we constantly had to look around to avoid bumping into other people or boats.

Well, we thought, maybe the view would make up for it.

Unfortunately and perhaps unsurprisingly, the reef has lost its mass and color, and we spotted only the occasional fish swimming by. There was still a good variety—a triggerfish or two circling their territory, a parrotfish here and there, some sergeant majors and a handful neon-blue damselfish gathering near a coral, to name a few. Randomly, but quite rarely, a small school of some other nondescript fish would cross our path. We did spot another pawikan from afar, but the crowd made it hard to swim after it (even without a toddler to mind), so the guide just took our camera with him to hopefully get some decent shots.

It’s hard not to feel disappointed, realizing that tourism has taken priority over conservation in one of our most beloved travel sites, especially in an area that is supposed to be and should have been heavily preserved. There should be a way to allow people to appreciate the beauty of Balicasag without overcrowding it and, as a result, overburdening and destroying the ecosystem. Maybe the reason we were all made to crowd at only one spot when the small island has great underwater views all around is to restrict the area affected by visitors, but the goal should be minimizing the detriment to the environment in the first place, and that goes for the ecology not just underwater but on the island itself.

It would be a good idea to actually schedule and limit the number of people visiting the area. At the very least, they could have played an educational video about the local marine life and how to interact—or not interact—with it safely (with translation into other languages) for people to watch at the waiting area. It might not do much, but it’s something.

Napaling Reef

We did have a gorgeous seafood platter lunch at the covered dining hall, but after the realization that the promised four-stop island-hopping adventure has been reduced to just that one disheartening spot, we asked to be brought to at least another site before heading back to our resort. (On a side note, it was aggravating how it took some convincing to get the booking agent to see how unacceptable it was to charge an exorbitant fee for an entire tour package and only deliver a quarter of it.)

On our way back to Panglao Island, the boat stopped midway so we could get in more snorkeling time. We asked our very young boat drivers for the name of the spot, but they didn’t even know. We suspect they just found a random point along the way to drop the anchor before we reached the end of our destination, but it didn’t matter. We saw more underwater activity there than we did during the entire one-hour slot at the supposed marine sanctuary.

Here’s the thing about Bohol waters, though: They’re so beautiful and vast that you need not go to Balicasag Island Marine Sanctuary to experience their magic. On New Year’s Day, we found ourselves heading to Napaling Reef, which we learned about from a tour ad in a couple of tricycles we’d ridden. A bit of online research also convinced us to give it a go, especially since it was just a 15-minute ride from our resort anyway. No boat transfers needed; no extra gear required save for mask (plus snorkel) for viewing, and a life vest for safety.

And because the current was hardly noticeable, and with the area for snorkeling having been cordoned off, visitors might not actually even need a guide (although they are required for those swimming with kids and they double as photographer-slash-videographer, which you would definitely want).

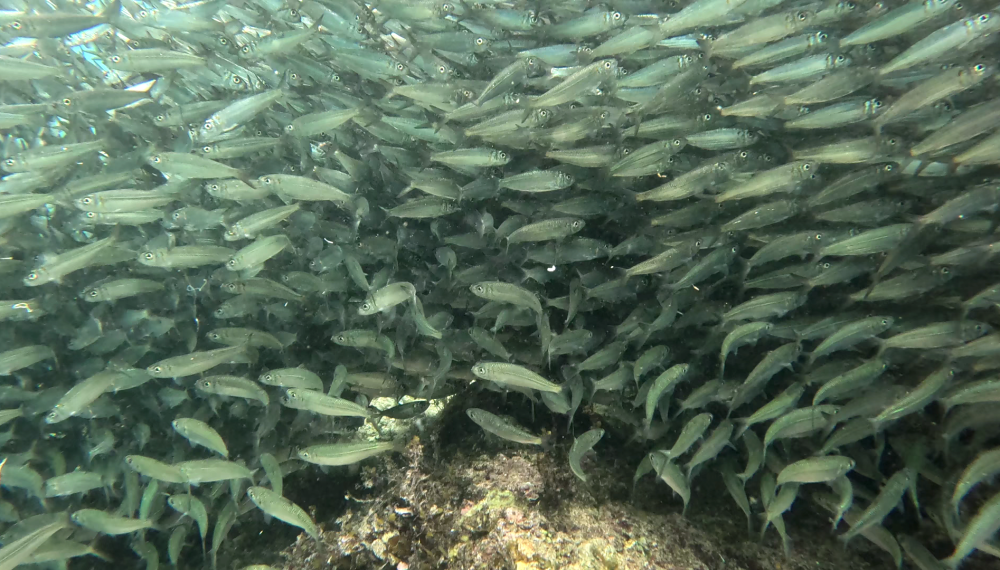

After waiting for an available lifeguard-guide, we were led down a short flight of stairs on the side of the cliff, taking care not to slip since it had been drizzling. We stepped into the cool water, and as soon as we dipped our heads below the surface—with our feet still touching the submerged foot of the stairs—we were met with a marvelous sight: a huge wall of sardines huddled together in a writhing mass of gray and silver, seemingly a million pairs of round, wide eyes staring back at us. The experience was, suffice it to say, as advertised.

Marvelous sight

When we moved closer, the school would disperse in delightful swirls, but immediately reconvene nearby. The guide said the fish, which gather at that side of the reef during the day to feed off the tiny shrimps there and then move to the other side of the cliff come nighttime, have gotten used to human presence, possibly after realizing the visitors weren’t really doing them any harm.

The area was also a bit crowded (you’d have to look out for “traffic” when trying to get nice underwater action shots), but even just snorkeling in a limited circumference already offers an exciting spectacle. We finally saw an underwater community teeming with life, the healthy-looking corals serving as homes to numerous marine animals. Aside from the sardines, there were parrotfish and triggerfish circling about as well. We saw some angelfish, needlefish, Moorish Idols, pipefish, seahorses, an eel, and so many other types of interesting-looking sea animals we couldn’t name. We also spotted a bird locally known as tikling swooping in for a snack every now and then.

Regrettably, the rain tends to wash some mud into the waters from the cliff, obscuring the underwater visibility. But unless the downpour continues, the mild current would eventually clear it all out again.

The other end of the approximately 1-kilometer snorkeling area offers an interesting view as well. There, they placed artificial reefs, which are structures set up to encourage coral growth that in turn stimulates the development of the ecosystem. Clearly, done right, tourism and conservation can and do coexist.