Theater 2024: Discerning patterns and possibilities

No longer based in Manila, yet still striving to see as much of its theater as possible, I definitely missed a number of shows this year—for instance, “3 Upuan,” “Mga Multo,” and “Nagkatuwaan sa Tahanang Ito,” which all lived brief, acclaimed lives at the Ateneo.

What follows, then, is an appraisal of Manila’s theater scene that’s more preoccupied with the patterns of its strengths, its limitations, its possibilities for growth.

Tanghalang Pilipino’s banner year

The Cultural Center of the Philippines’ (CCP) resident theater company staged two of 2024’s most intellectually satisfying productions. “Pingkian,” an original musical about Emilio Jacinto and the Katipunan, was that rare play propelled narratively by a progression of ideas, rather than conventional plot points. (A key number—the year’s most thrilling, in fact—essentially rewrote the Kartilya, the Katipunan’s bible, into a rousing, rap-sung manifesto of freedom and personhood.) Meanwhile, “Balete,” partly hewn from two of F. Sionil José’s works, was a marvel of inventive theatricality, its lucid dramatization of the specter of feudalism evidence of what genuine artistic collaboration could achieve.

Together, these shows became ardent interrogations into what makes—or breaks—a nation. They were also exemplary additions to the company’s distinctive body of work in the past decade: along with “Batang Mujahideen,”“Nekropolis,” “Ang Pag-uusig,” “Mabining Mandirigma,” and “Mga Buhay na Apoy,” theater that unflinchingly confronts what it truly means to be Filipino.

‘Medea’ and seeking the classics

Post-curtain at Tanghalang Ateneo’s “Medea” in November, director Ron Capinding spoke of the company’s near-future direction to pursue the classics in honor of the late Ricky Abad. “Medea” was a perfect herald of that future: an ancient text deftly revived, its primal histrionics made intelligible for modern viewers—despite Rolando Tinio’s baroque Tagalog translation.

The larger questions it raised were also worth pondering for other companies: How do we make great art accessible to audiences besieged by brain rot and TikTok? What and where is the place of these stereotypically dusty tomes in a landscape saturated with jukebox musicals?

Months earlier, The Sandbox Collective had hinted at a tangential answer, via its rip-roaring production of the modern cult classic “Little Shop of Horrors”—the success of, among other reasons, intelligent casting. In both cases, it was clear audiences will flock to shows that meet them halfway. The Atenean kids I watched “Medea” with ate up every single crumb of it!

Two musicals and popular success

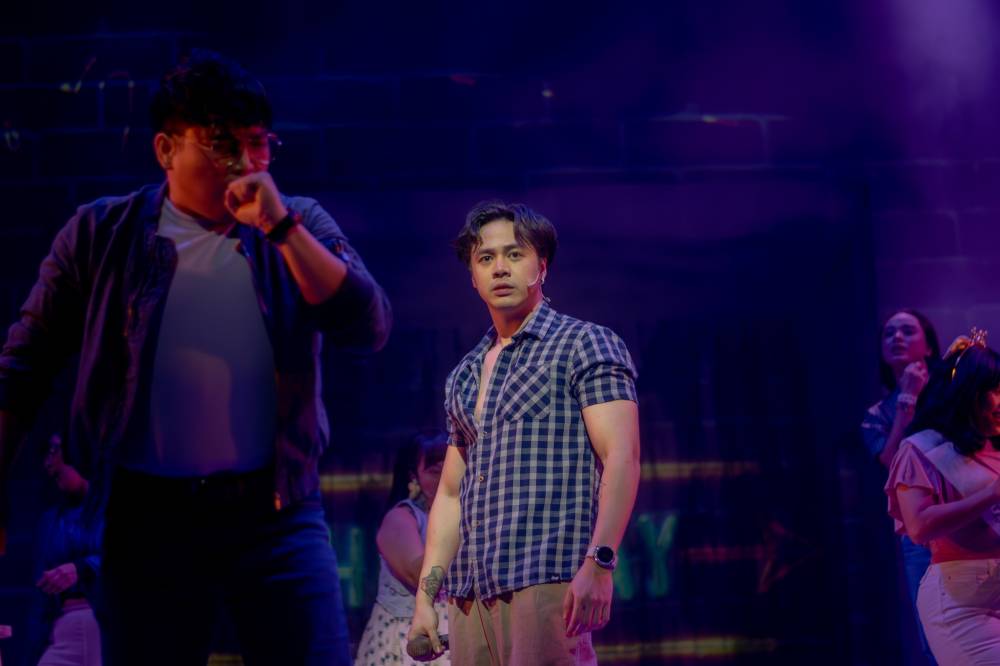

Without question, two of the year’s biggest popular hits met viewers halfway—and knew their audiences. The Philippine Educational Theater Association’s adaptation of the John Lloyd Cruz-Bea Alonzo romcom “One More Chance” sold out its three-month run (from April to June) even before opening—a first in company history. Barefoot Theatre Collaborative’s (BTC) “Bar Boys,” based on the titular film about four aspiring lawyers, enjoyed similar success, its initial three-weekend run in May spawning a six-weekend rerun later in the year.

Far from flawless, both were nonetheless hugely enjoyable nights at the theater. And how they drew the crowds—lawyers and law students at “Bar Boys,” just about every demographic imaginable (that had presumably seen a Star Cinema romcom) at “One More Chance.” Even people I knew who weren’t regular theatergoers were asking about these shows—a reliable metric of success, I’ve found. Most important, their respective companies clearly put in the work into marketing these musicals, from publicity to partnerships to, simply put, transforming them into “theatrical events.”

Right performers, right roles

Some performances were Herculean inevitabilities: Nonie Buencamino in “Balete,” Miren Fabregas-Alvarez in “Medea.” Some felt like kismet: actors seemingly born for their roles, like Reb Atadero’s Seymour, equal parts comic and loser, in “Little Shop of Horrors”; Sheila Francisco and Juliene Mendoza in “Bar Boys,” twin experts in the emotional grammar of the stage; Leo Rialp as an unholy cardinal in Encore Theater’s “Grace”; and—my bias—Sam Concepcion’s Popoy in “One More Chance,” a sublime marriage of performer and skill set birthing local musical theater’s newest leading man (or to borrow from The Knee-Jerk Critic, a true “quadruple threat”).

Some other performances felt revelatory, an actor finally given a sizable spotlight and owning it completely: Benedix Ramos in “Bar Boys”; Julia Serad in “Little Shop of Horrors”; at the Virgin Labfest, Jam Binay as a demented Catholic schoolgirl in “Sa Babaeng Lahat” and Joshua Cabiladas as a millennial “dirty old man” in “Ang Munting Liwanag sa Madilim na Sulok ng Isang Serbeserya sa Maynila.” With Maronne Cruz (Emilia in Company of Actors in Streamlined Theatre’s “Othello”) and Krystal Kane (juggling a dozen or so parts in Repertory Philippines’ “I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change”), it was two former Ateneo Blue Repertory leading ladies slaying—yet again.

The trend of film and TV stars “crossing over” to theater also continued, and amid numerous misses was an undeniable hit: Sue Ramirez, utterly luminous from her first entrance as Audrey in “Little Shop of Horrors.”

Design that earned its place

I mean design that effectively evoked a play’s essence. In “Balete,” two relatively new names—Wika Nadera (set) and Carlos Siongco (costumes)—jointly conjured the characters’ old-world, agrarian aesthetic. GA Fallarme’s projections in “I Love You…” and Miguel Urbino’s sound design for Repertory Philippines’ “Betrayal” were epitomes of restraint and sophistication.

In “Buruguduystunstugudunstuy,” the Parokya ni Edgar musical at Newport World Resorts, Raven Ong’s outlandish trash-bag gowns best captured the musical’s inane spirit. Bituin Escalante’s hair in “Pingkian” was its own entity; so, too, was Alvarez-Fabregas’ cape in “Medea.”

The eternal question of access

Lastly, the Samsung Performing Arts Theater this year became an inadvertent site for continuing conversations on access. On the one hand was “Request sa Radyo,” the play about a Filipino migrant worker in America headlined by Lea Salonga and Dolly de Leon, and which boasted a fully functioning apartment set by Tony-winning designer (and co-producer) Clint Ramos. With top tickets costing almost P10,000, “Request” begged the question: Who exactly was meant to see this “coming together” of beacons of “Philippine pride,” to quote its website? Certainly not most ordinary theatergoers, whom it shut out with ticket prices unparalleled in their exorbitance in recent local history. If anything, it all betrayed an anomalous marketing direction so detached from present realities.

On the other hand was “Mula sa Buwan,” Pat Valera and William Elvin Manzano’s take on “Cyrano de Bergerac.” Returning under BTC, it offered a far more egalitarian theatrical event—one closely attuned to the pulse of local theater. At the full-house performance I attended, the crowd was diverse, with many young-looking members—some of them students on sponsored tickets, I was told—all laughing, crying, and reacting to the whole thing. Through mastery of social media, a dedication to cultivating its fan base, and the sheer will to make itself affordable to as many people as possible, “Mula sa Buwan” illustrated what inclusive, accessible Filipino theater could look like.

Further, accessibility can also mean using subtitles, as in “One More Chance.” Or announcing performance dates and schedules reasonably early enough so people can plot their viewings. Or considering the practicality of watching two shows in one day (why endure Manila traffic on separate days?) and leaving ample time for people to travel between matinees and evening performances (why even start at 7:30 p.m. on Saturdays?).

Regardless of the means, the end remains the same: We need a theater landscape that strives to open its doors to more people, even from places beyond Manila—especially from places where regular theater is rare and therefore could be a precious, life-changing experience.