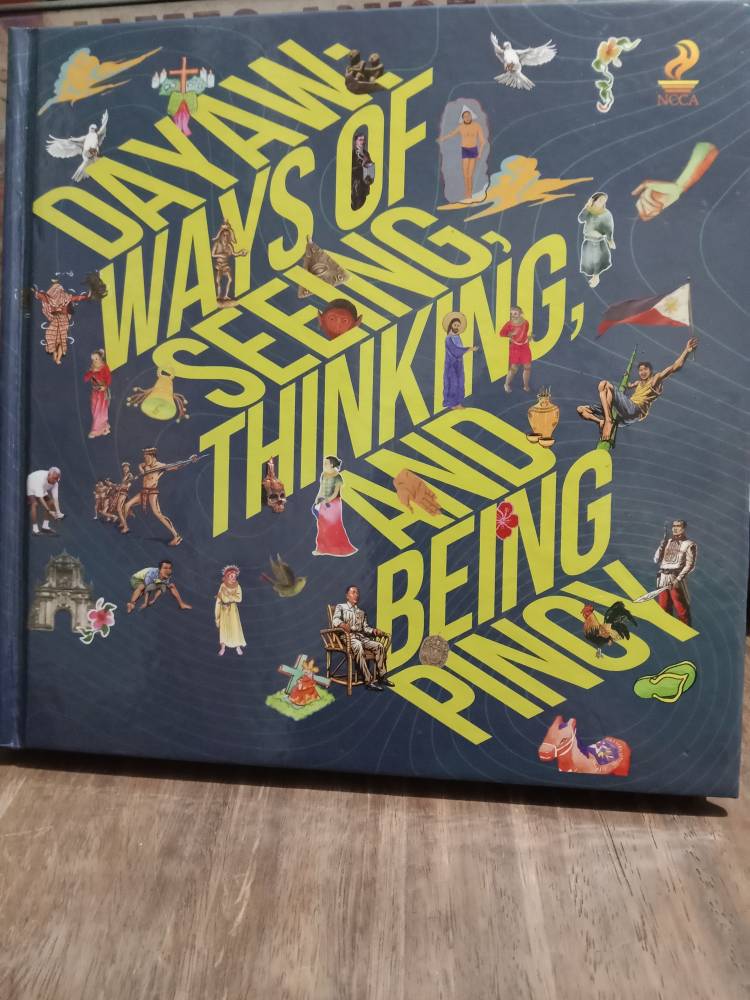

This book is a journey of discovery for young Filipinos

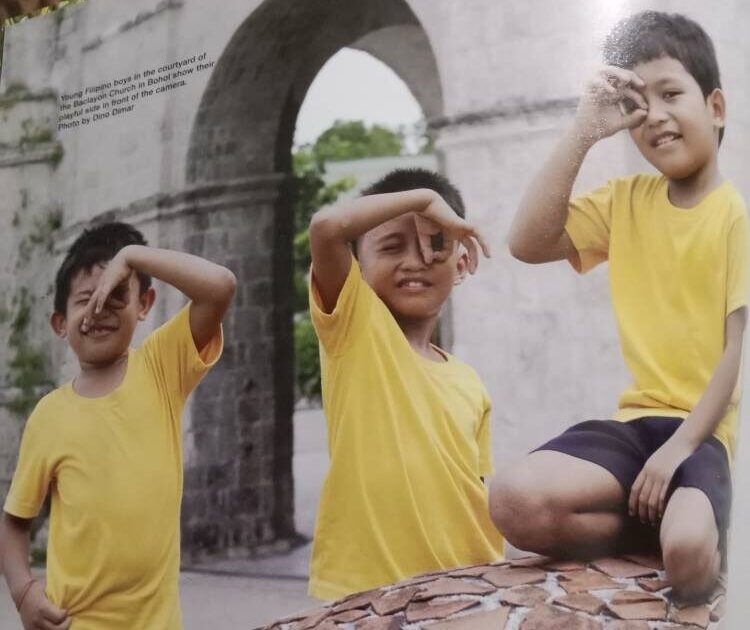

A handsomely illustrated book just published by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) has a long title: “Dayaw: Ways of Seeing, Thinking, and Being Pinoy.” It is written by the late playwright Floy Quintos and Florence M. Rosini, with photos by Dino Dimar and a foreword by humanities professor Felipe Mendoza de Leon.

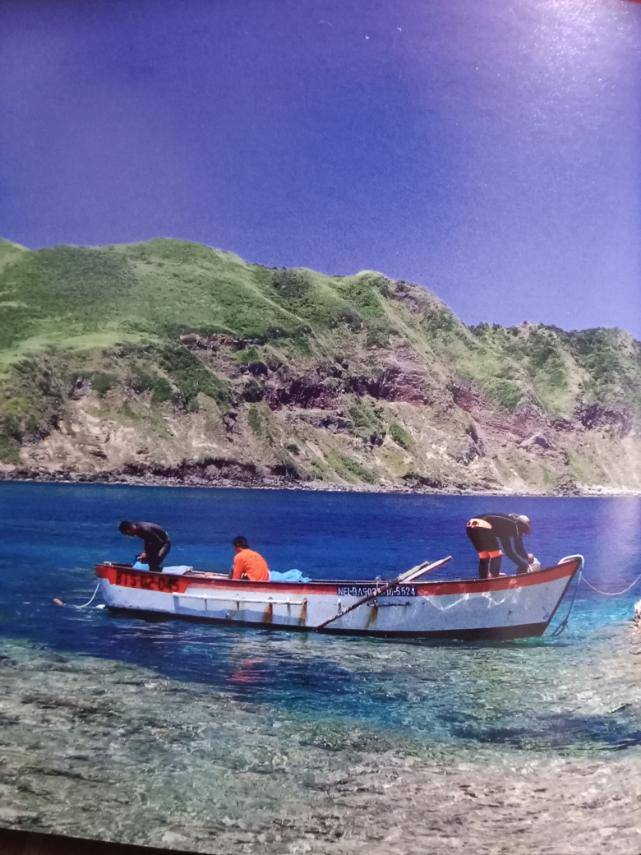

The book covers practically the whole gamut of the Philippine experience—it segues from the precolonial past to the present and then back again.

There are archeological discoveries that go back hundreds, even thousands of years, proving our ancestors were literate, had diplomacy and spiritual depth. The authors write, “Our ancestors had a life, and what a rich and colorful life it was!”

Excavations led by Dr. Armand Mijares of the University of the Philippines in the Callao Caves in Cagayan from 2010 to 2015 yielded fossils, a foot bone, seven teeth, and two fingers 67,000 years old—older than the Tabon man of Palawan. In Rizal, Kalinga province in 2014, archaeologists discovered the remains of a huge rhinoceros 709,000 years old that had been hunted and butchered.

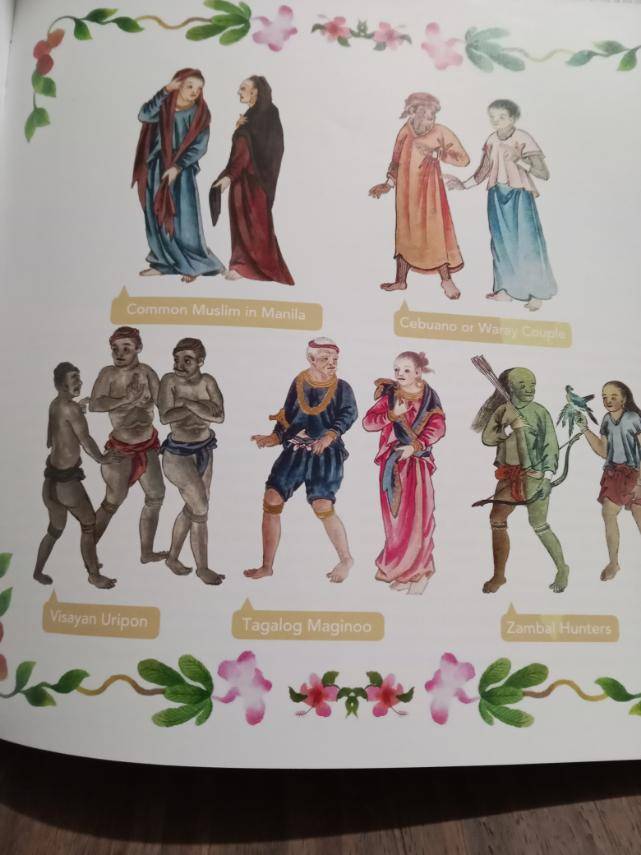

The Boxer Codex (1590) shows that our ancestors had a sense of style, with a well-dressed lady from Cagayan Valley wearing a gold appliqué closure; loose blouse and a camisa from a Tagalog man; the Visayan Pintados with tattoos; plus reptile and insect motifs to “capture the ferocity of the animal spirit guide” (among the Ibaloi, Kalinga, and Ifugao).

Our ancestors, like others from ancient culture, had the custom of pabaon, or gifts to ensure the comfort and prestige of the departed. Outstanding examples can be found in many of our museums.

“The collections of both the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas and the Ayala Museum showcase the creativity and design skills of our ancestors,” Quintos wrote. These include necklaces, earrings, bracelets, loose beads, even whole belts.

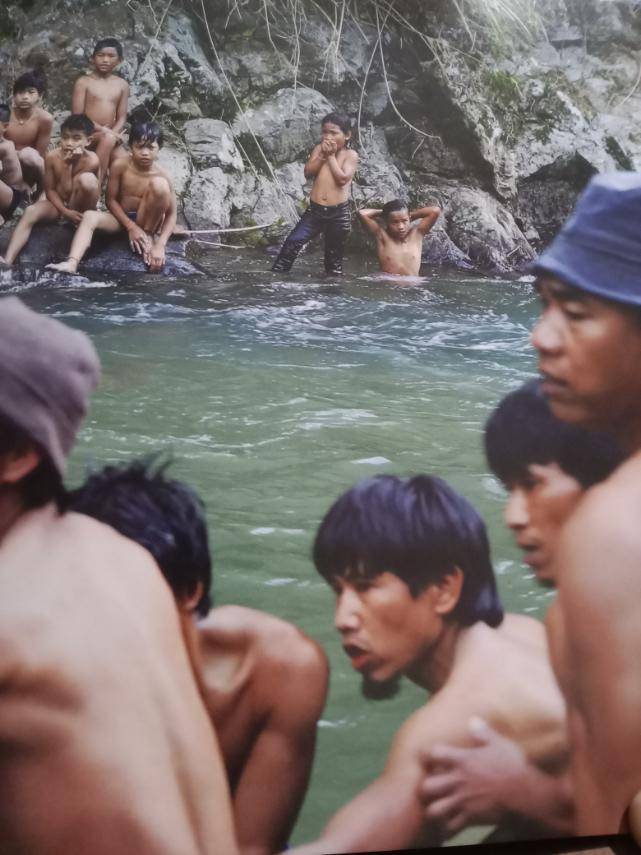

Before the arrival of Magellan in 1521, the introduction of Christianity, and the naming of the islands after Philip II of Spain, our ancestors practiced the animist religion, believing that souls and spirits dwell in all of nature’s creations. Man is a steward, not owner of the earth, and there were mediums or shamans who contacted the spirit world.

Our superheroes

The book then delves into excavated pottery, heirloom beads, and other precolonial artifacts that are valued today as art and museum pieces, but which were functional during olden times. The same can be said, the authors point out, for contemporary folk art like the works of the master carvers in Paete, Laguna, and the higantes of Angono, Rizal.

The book makes a strong case for our own superheroes, the heroes of our own epics, like Lam-ang, Aliguyan, Tud Bulol, and Darangen. And while other cultures have only one epic, the Philippines has more than 20 that have been documented. More may have been lost or forgotten.

“Each epic represents the shared culture, experience, and aspirations of a particular group of people,” Quintos wrote. “These were passed on, not through written texts but through chanting and singing during rituals and community gatherings.”

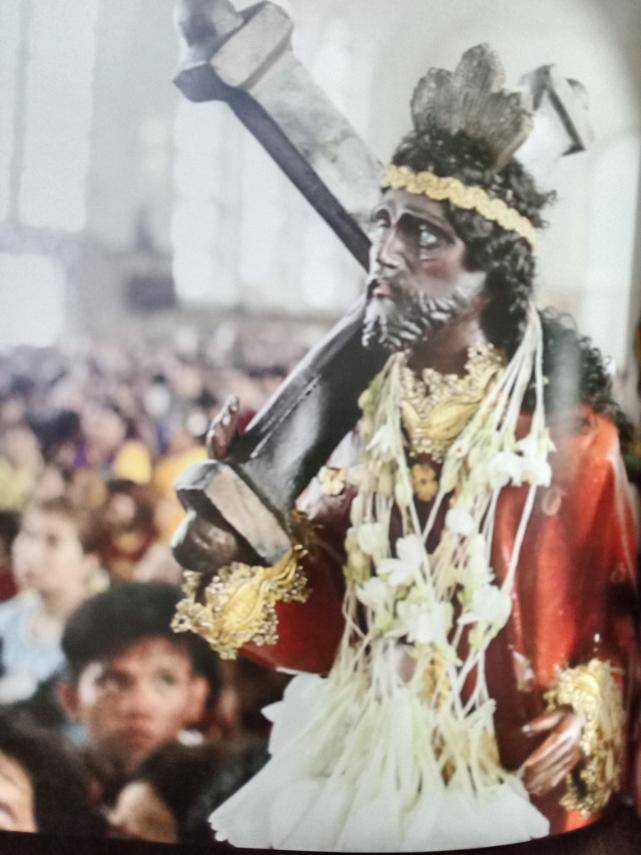

The second part of the book, written by Rosini, is a veritable apotheosis of landmarks such as Intramuros, the restored Metropolitan Theater, Binondo, and Escolta; our devotion to the saints; our culinary heritage; the Komedya and the Kundiman; traditional chanters and singers; martial arts like the arnis (Tagalog and Hiligaynon speakers) or estokada (Cebuano speakers); folk dances; and the decalogues of our national heroes.

The authors end with a wish for high school students who are the target audience of this book: “Keep believing in the better Philippines and Filipinos that this book can help make possible.”