Time as great arbiter of grief in Guelan Luarca’s ‘3 Upuan’

Here’s something you only ever learn when the time actually comes: Grieving a loved one’s death is a bizarre, alienating experience. It forces you into a different timeline, a kind of temporal suspension in which your grief is only ever your own, while life around you goes on as if nobody has died. The only way the rest of the world can know your grief is if you actually articulate it—if you ever manage to do so, that is.

This alienation-in-grief, this state of being adrift in time and space, is what preoccupies Guelan Luarca’s “3 Upuan,” a heart-wrencher of a play that’s easily best-of-the-decade material. As precise as it is profound in its rumination on what it’s like to lose someone, this play is perhaps the most persuasive exploration of the subject Philippine theater has seen of late. Put simply, it gets it all right.

It understands, for example, that grief is about perspective. Throughout this play, the characters of three siblings each alternate as narrators, guiding the audience through their individual experiences mourning the sickness and death of their father. Jers, the eldest, is an academic whose idea of processing loss hinges mainly on the vocabulary of the humanities that he deploys daily in the classroom. Jack, the middle son, is a visual artist who finds—and loses—himself, and his sorrows, in sculpture and poetry.

And Jai, the youngest, is a journalist based in America, whose grasp of grief is perhaps, understandably, the most vivid, evocative, grounded.

In a span of 90 minutes, “3 Upuan” takes the audience on a journey that begins at the siblings’ father’s deathbed—but then quickly unfurls backwards and forwards across time, and beyond this single family unit, into a remarkably complex exploration of the origins of human sadness.

Pivotal event

Grief, this play asserts, never really goes away—it only grows or shrinks with time, stuck to our psyches and forever dictating the way we perceive the world after that pivotal, sorrowful event. It is why the world spins the way it does; why people behave the way they do.

In other words, time is the great arbiter. In the play, each sibling becomes ensconced in a world of their own grief, living out a timeline separate from the rest, even as they ostensibly experience the fact and aftermath of their father’s death together.

Jers and Jack pass the time talking hypotheticals in the hospital. Fast-forward after the funeral, Jack and Jai enjoy the most mundane drives around town. Much, much later, Jers and Jai become bonded by yet another tragedy in the family. In all this, we see each sibling existing in two presents: the one that everybody else in their fictive world can see, and the one only they can perceive, shaped by their individual grief. Each effectively becomes a cipher to the others.

The central mystery of this play, then: How does one stop being that cipher of grief?

Here, Luarca proffers the same answer: time. If grief is an experience that halts time, it is also one that can be understood and articulated fully only with time. In this sense, “3 Upuan” becomes a most articulate play about articulating the seemingly inarticulable.

Drawing partly from the French thinker Jacques Lacan, the play is a journey of making sense of the senseless. Articulating their grief becomes, for the characters, a project of piecing together memories, sharing moments of fleeting joy, learning to see the world from the others’ eyes, and finding the right words to capture that singular, incomprehensible feeling. It is a project that takes time, and can only ever be finished with enough time.

Intellectual rigor

Staged in a 60-seater repurposed classroom, Scene Change and Areté’s production of the play (directed by Luarca himself) forces you to confront the characters’ grief head on—and perhaps also reflect upon your own. This intimate setup also renders “3 Upuan’s” intellectual rigor crystal-clear: how this play is structurally unassailable, expansive in its imagining of incident, in how it puts into words the past, present, and future.

That the production somehow miraculously manages to make full sense of the script is a testament to Luarca as director, who has tamed and turned theatrically coherent the novelistic impulses of his own writing. The design here is simple yet utterly effective: mixed-and-matched ceiling fluorescents by lighting designer D Cortezano, pitch-perfect atmospheric sounds by Julia Vaila, and the smartest use of video and projections I’ve seen of late by Teia Contreras.

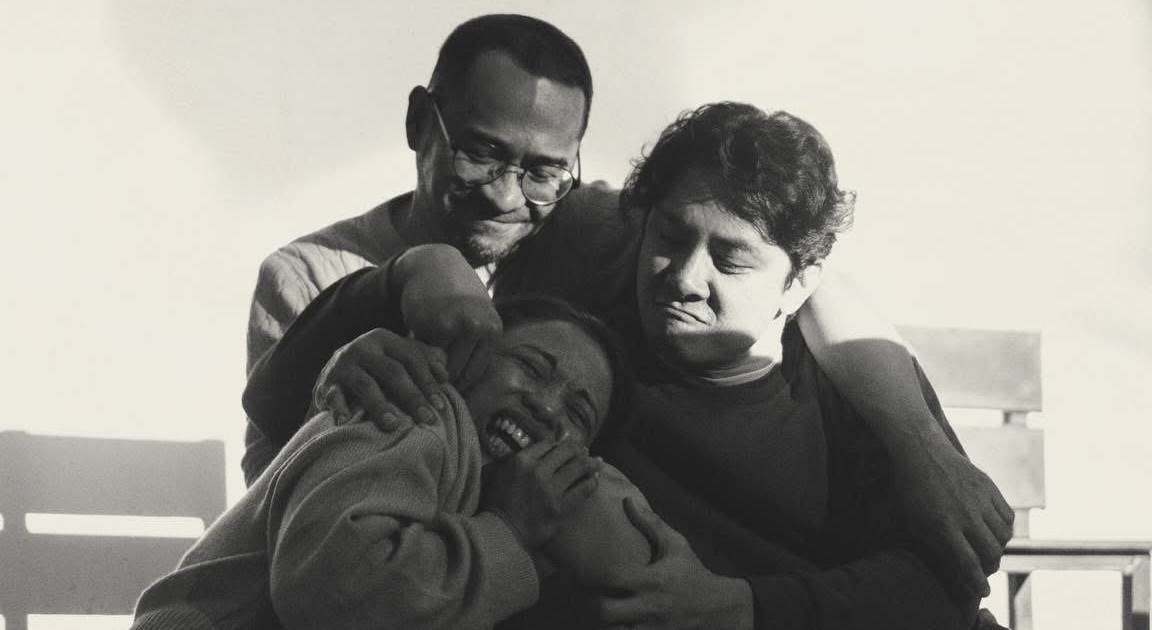

The cast Luarca has assembled, all returning from last year’s premiere, are impeccable in the way they plumb the emotional recesses of their characters: Jojit Lorenzo as Jers, JC Santos as Jack, and—in what has been rightfully labeled a career-best performance—Martha Comia as Jai, a beacon of actorly precision, down to her trying-to-belong-but-could-never-belong American accent as the US-based sibling.

Between this play and “The Impossible Dream,” which recently enjoyed a one-weekend revival at the Philippine Educational Theater Association’s Control + Shift Festival, Luarca has clearly distinguished himself as the preeminent Filipino playwright of his generation. If writing for the theater is an act of radical imagination—of conjuring infinite possibilities, redefining the real, and stretching the limits of our emotive capacities—then Luarca’s body of work is, for lack of a subtler term, peerless.

Cathartic gift

In “The Impossible Dream,” Luarca uses the straightforward premise of a fictitious encounter between Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and Ninoy Aquino as a launchpad for meditating on ideas of revolution and heroism in the post-truth age (and all done in such piquant language!). Likewise, in past plays such as “Nekropolis,” “Desaparesidos,” and even the imperfect “Ardor,” he has consistently pushed for dissections of the Filipino consciousness—in its immediate and imagined forms—that none of his peers could, at present, ever claim to equal.

In “3 Upuan,” Luarca has visibly taken a more inward-looking turn—yet one that is no less meticulous in its explication of a very Filipino human-ness. Those who’ve never grieved for a loved one will nonetheless find in this play a work of astounding sophistication and emotional maturity.

But if you’ve ever gone through the roller coaster of watching a loved one die, anticipating their death, pregrieving the loss to come, then actually grappling with that loss and trying to make sense of the all-consuming aftermath, this play is a cathartic gift.

“3 Upuan” concludes its sold-out run on Feb. 23 at the Joselito & Olivia Campos Teaching Laboratory, Areté, Ateneo de Manila University, QC.