Two artists, one legacy: Fil and Janos Delacruz’s shared canvas

Fil and Janos Delacruz are a leading father-and-son duo in Philippine art, following in the footsteps of notable paternal pairings like Angel and Michael Cacnio, Romulo and Jonathan Olazo, and Mauro Malang and Soler Santos. In many ways, the son’s work reflects the father’s, and conversely.

The Delacruzes once again showcase their familial artistic talent with separate but simultaneous exhibits at Art Lounge Manila in The Podium, Mandaluyong—Fil with “Saglit” and Janos with “Tadhana.” Both exhibits run until Aug. 5.

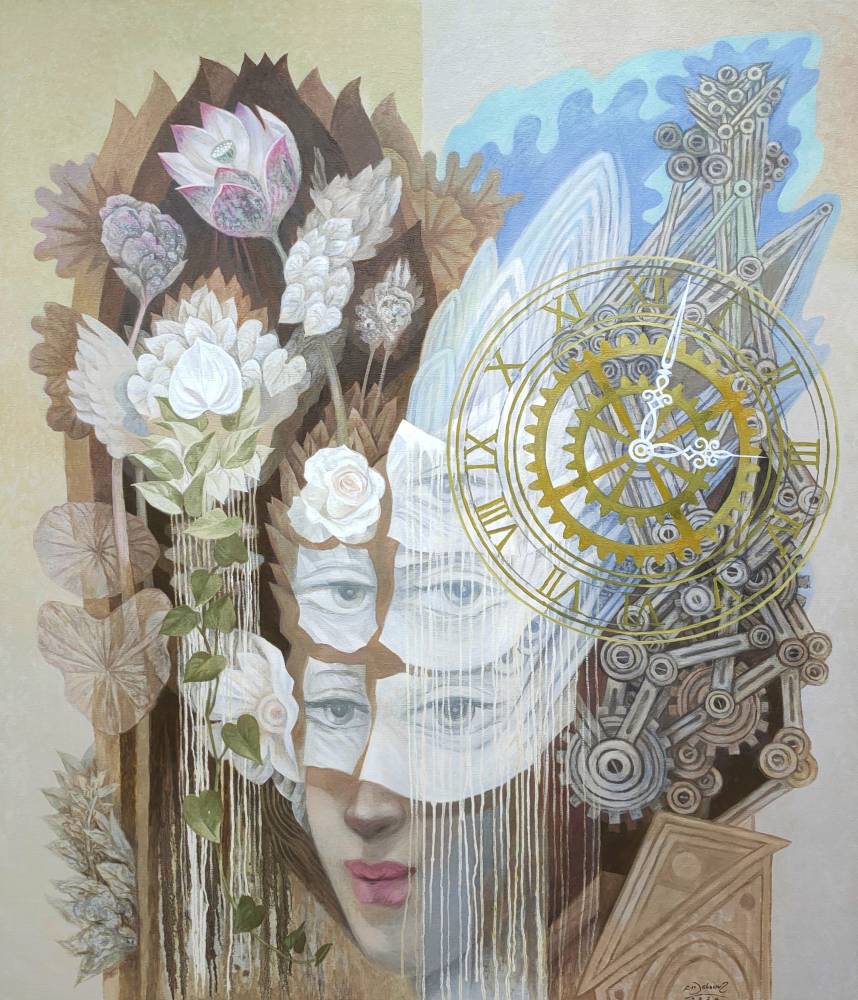

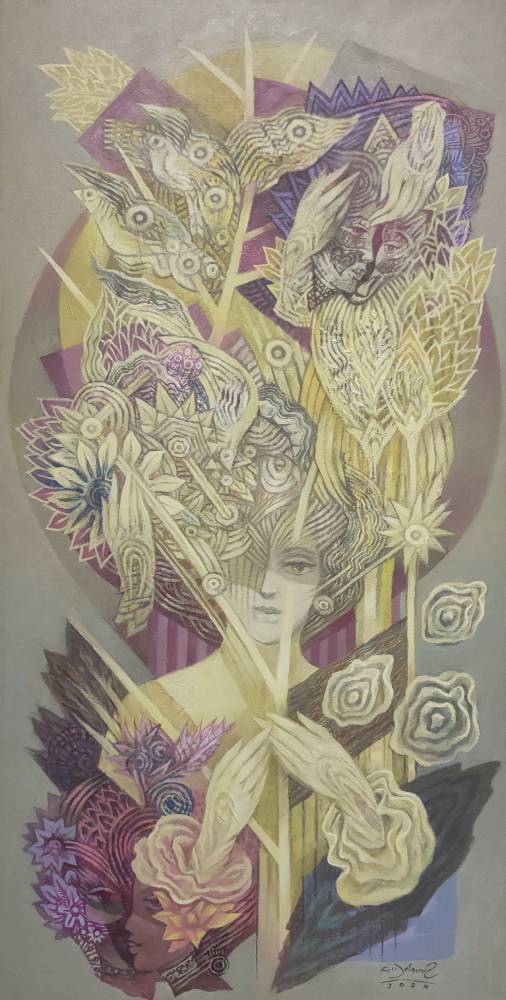

Fil’s “Saglit” is inspired by the Heraclitean philosophy that change is the only constant in life. Featuring mainly oil-on-canvas works, the elder Delacruz explores themes of time and mortality.

His iconic “Diwata” series presents these figures as mythical entities from folklore, symbolizing life’s fleeting nature and creating an intimate connection between artist and viewer. This series also serves as a memorial to Fil’s wife, Marialuz “Marlou” Buenaflor Delacruz, who died in January.

In “Tadhana,” Janos delves into themes of longing, destiny and the complexities of love. His exhibit includes works on canvas, paper and reinforced resin, documenting his visual journey and capturing the intricate evolution of relationships and personal growth.

Both father and son have been recognized with the Benavidez Award for outstanding students of fine arts at the University of Santo Tomas (Fil in 1973, Janos in 2006), and the prestigious CCP Thirteen Artists Awards (Fil in 1992, Janos in 2018). They have previously held simultaneous but separate exhibits, highlighting both the complementarity and divergence in their art styles and trajectories.

Art indeed is in the genes, and Fil and Janos conduct their artmaking as a dialogue of idioms, styles and worldviews.

Indigenous cosmology

Filemon Perez Delacruz (born 1950) is renowned for his paintings and prints, especially those depicting members of indigenous cultural communities. He is particularly known for his work with the Manobo of Kalamansig, Sultan Kudarat, with whom he lived for three years, supporting their struggles against land grabbers and loggers threatening their ancestral lands.

Fil’s art is rich with indigenous symbols such as the diwata, lizard, egg and skull, reflecting the values of the Lumad, the indigenous people of Mindanao.

While his earlier works used Manobo cosmology to highlight themes of displacement and oppression, his recent explorations have shifted toward environmental advocacy and universal themes, such as the matriarchal spirit of Philippine forests and the dualism in nature’s flora and fauna.

His latest exhibit, “Saglit” (Tagalog for “moment”), encapsulates the fleeting nature of life, potentially serving both as a meditation on mortality and a celebration of art’s ability to capture and extend beauty. A constant theme in his work is the iconography of the woman, which remains central to his artistic expression.

Transience

In “Saglit,” according to curator Carlomar Daoana, Fil’s women are depicted with a subdued grace, juxtaposed with symbols of time such as clocks, hourglasses and gears. These figures serve not as subjects of time but as reminders of it, akin to the Greek goddess Ananke, who embodies the inevitability of time’s passage. They convey the message that, regardless of our achievements, our destiny ultimately aligns with the biblical sentiment of “dust to dust.”

However, despite their role as messengers of our fleeting existence, these women are portrayed as flourishing figures. This portrayal suggests that there is value in being conscious of time, allowing us to appreciate the transient nature of life.

In addition to his oil paintings, Fil presents sculptures that reimagine his “Diwata” iconography in resin. These handpainted works, rendered in verdigris and other muted yet captivating colors, enhance the theme of dualism and promise a delightful surprise for Fil Delacruz enthusiasts.

Hybrid forms and fate

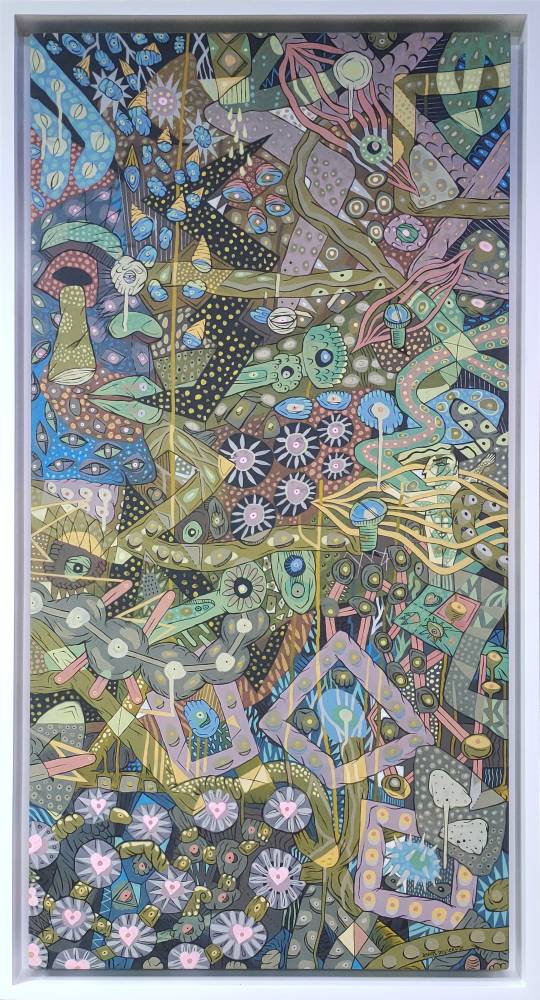

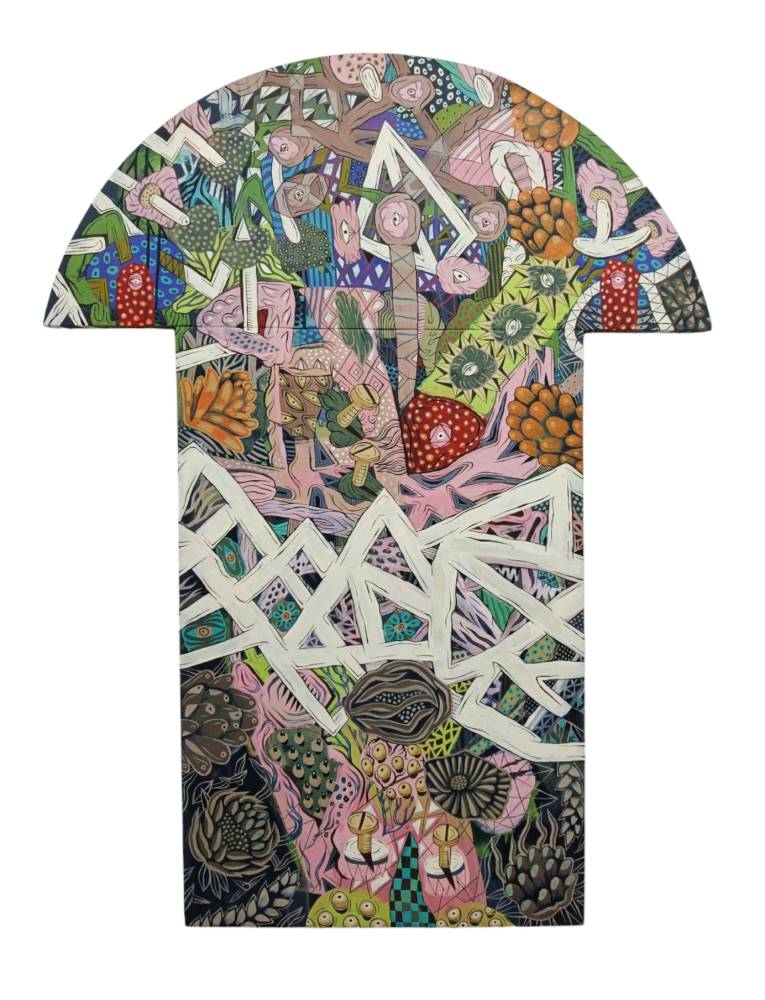

Much like his father, Janos is renowned for his graphic skills, initially evident in his drawings of hybrid figures and later in his printmaking, which has earned him numerous national awards.

Following in his father’s footsteps, who has conducted printmaking workshops, notably at the University of the Philippines fine arts school, Janos has also been giving similar workshops in Mindanao.

For “Tadhana,” Janos continues his visual journaling by presenting works on paper, handpainted reinforced resin and canvas. These pieces are characterized by dynamic lines, shapes, colors and patterns.

“Tadhana,” meaning “fate” or “destiny” in Tagalog, sees Janos exploring themes of human drive and despair through the lens of romantic love. The exhibit delves into whether romantic love is predestined or arbitrary, capturing the tumultuous emotions and complexities that come with it.

“Tadhana” also serves as a heartfelt tribute to Janos’ late mother. His autobiographical approach illustrates how her passing prompted him to reflect deeply on life and relationships. Through his art, he navigates personal doubts and emotions, utilizing his creative process as a form of private therapy. In doing so, he, like his father, transforms personal grief into a public narrative.

Through their personal losses—Janos losing his mother and Fil losing his spouse—the Delacruzes have elevated their art to more contemplative and profound levels. They embody Bertolt Brecht’s idea that true stature is shown by how one mourns, and they have made mourning an element of social progress through their artistic endeavors.