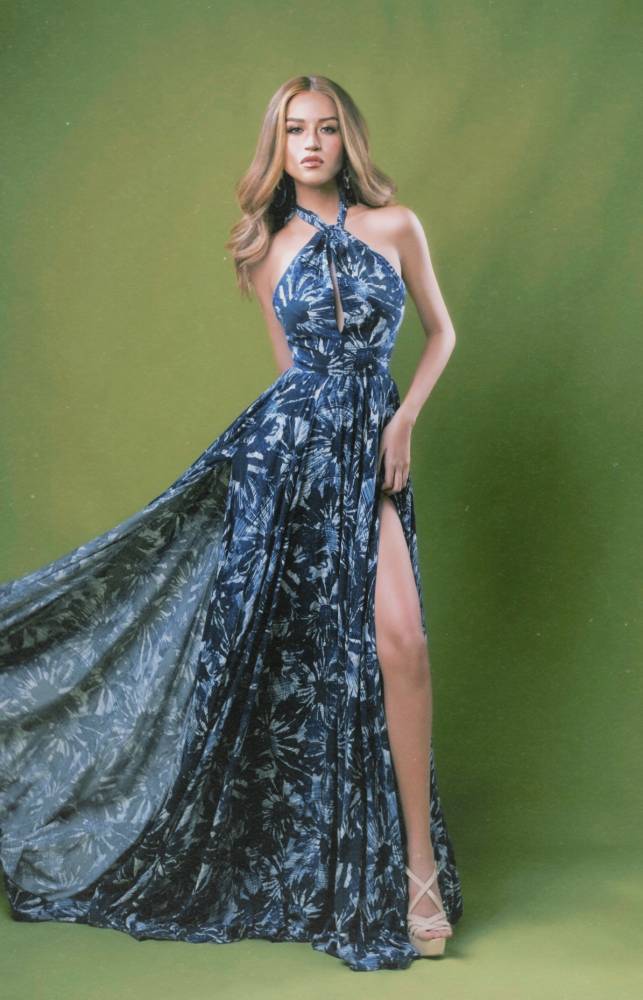

What beauty gives, what it takes, and what it costs

I always knew I was pretty. I just never thought it mattered. Growing up, beauty existed on the periphery of my life. Present, but not something I organized myself around. While my aunt and I sat through “America’s Next Top Model” marathons, the girls I wanted to emulate were Annabeth Chase and Rory Gilmore: characters whose intelligence eclipsed whatever their faces happened to look like.

People told my mother I was smart. Charming. And then pretty. Pretty was always just an afterthought in my existence.

Brains over beauty

Early on, I learned what to invest in. I joined quiz bees and spelling competitions, history bowls, and writing competitions with the school paper. I ran for student government and eventually became student body president. I did theater. I never wore makeup to class. I didn’t even party until my final semester of senior year. I didn’t get my first boyfriend until then either.

And when I did, it surprised everyone: a German athlete from the international school next door.

Even then, my appeal was framed as novelty, not inevitability. For a long time, I wasn’t the pretty one in my friend group. I was the nice one. The funny one. The reliable one. Docile and fun like a sunny retriever.

But almost a decade later, that hierarchy has inverted. Now, most people assume I have no personality at all.

The shift didn’t arrive with intention. At university, I became pretty, or perhaps more accurately, I became legible as such. Post-lockdown revenge travel gave me a tan. I dyed my hair blonde. My body changed, not dramatically, but decisively enough. Nothing about my interior life shifted. The ambition, the curiosity, and social ease had always been there. But now, those traits landed differently.

Wanted for how I look versus who I am

What followed was a strange temporal whiplash. People I had admired from afar in high school—celebrities, public figures, men who once existed half a world away—now wanted me. It was flattering and disorienting. I had imagined meeting them in a hundred ways, all of which presumed a different version of myself.

Standing across from them years later, I felt unchanged inside, only refracted through a new surface.

What unsettled me was not the attention, but the growing sense that it depended on my best angles—on a version of myself I wasn’t always prepared to maintain. I didn’t yet know how to be wanted when I was ordinary.

As a single woman, loneliness hasn’t disappeared; it has simply become harder to articulate. I have more options than I ever could have imagined, and yet choosing feels riskier. I cannot tell if I am wanted or simply wanted for what being with an attractive woman represents.

Underneath the tan, the blonde hair, and the body that now reads as currency, I am still myself. I don’t want to be good enough for everyone. I want to be chosen for reasons that don’t photograph well.

“Too pretty to be taken seriously”

In 2021, I moved deeper into climate activism and became a non-government organization (NGO) founder at nineteen. The new attention opened doors quickly and generously. I led with the ambition and conviction I had cultivated long before anyone cared what I looked like. Meetings came easily. Collaborations multiplied. People listened more closely.

My newfound conventional attractiveness proved to be a double-edged credential. Before, I never questioned why I was in a room; I knew I belonged there. But for the first time, I couldn’t tell whether I was being heard for my thinking or simply tolerated because we live in a country where ideas are easier to champion when the person delivering them is easy to look at.

Beauty, I realized, doesn’t erase merit. It destabilizes the metrics by which merit is recognized.

That tension followed me into journalism. Sometimes I worry about being “too pretty to be taken seriously”—a concern that sounds unserious until you’ve watched credibility thin out the moment it’s aestheticized. While it’s true that the media prefers certain faces, there seems to be an unspoken rule about staying on the fine line between beauty and credibility. Beauty can amplify a voice, but it can just as easily flatten your authority.

Beauty as a condition

Right before I turned 22, I joined a national pageant. Friends had done it to leverage their own NGOs, and recommended that I do the same for mine. I had also just come out of a long-term relationship, and the timing felt reckless enough to be right.

For years, I believed I was above pageantry. I was skeptical of its rankings, colonial beauty standards, and reduction of women into stereotypes and superficial titles. But moral distance, it turns out, is easier to maintain when you’re not being invited in. I scoffed at how pageantry reinforced the idea that advocacy only seemed to matter when it arrived attached to a beautiful woman, whilst paradoxically benefiting from that same logic.

The world treats beauty as an arrival point. In reality, it is a condition. One that expands access while narrowing margins for error. You are listened to more quickly, doubted more loudly, and forgiven less generously.

Realizing you are pretty doesn’t end the story. It complicates the plot.

Multiplicity without question

For decades, women have been asked to choose between archetypes—the Audrey or the Marilyn—as if complexity itself were a contradiction. Never both. And yet both Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe were intelligent, strategic, and deeply self-aware; society simply refused to hold those truths at once.

Elizabeth Holmes, the disgraced founder of healthcare scam Theranos, famously lowered her voice to be taken seriously—a reminder that credibility, for women, often requires self-erasure and dissociation from femininity.

It is almost as if the more feminine and conventionally attractive you are, the more your beauty aligns with the male gaze, the less your ideas are permitted to matter.

As a woman, you are allowed one defining trait. Pretty or smart. Desirable or serious. Men, meanwhile, are granted multiplicity without question—handsome and intelligent, ambitious and emotional, driven rather than delusional. They are allowed to be complex. They are not asked to collapse themselves the way women are.

Women, by contrast, are offered a false economy: choose beauty or legitimate authority, but never expect to keep both. And realizing I am pretty did not give me power; it revealed the cost of being seen at all.

The work, now, is refusing to simplify myself to make that visibility comfortable for others.