What SB19 and Rico Blanco’s shared stage may mean for P-pop

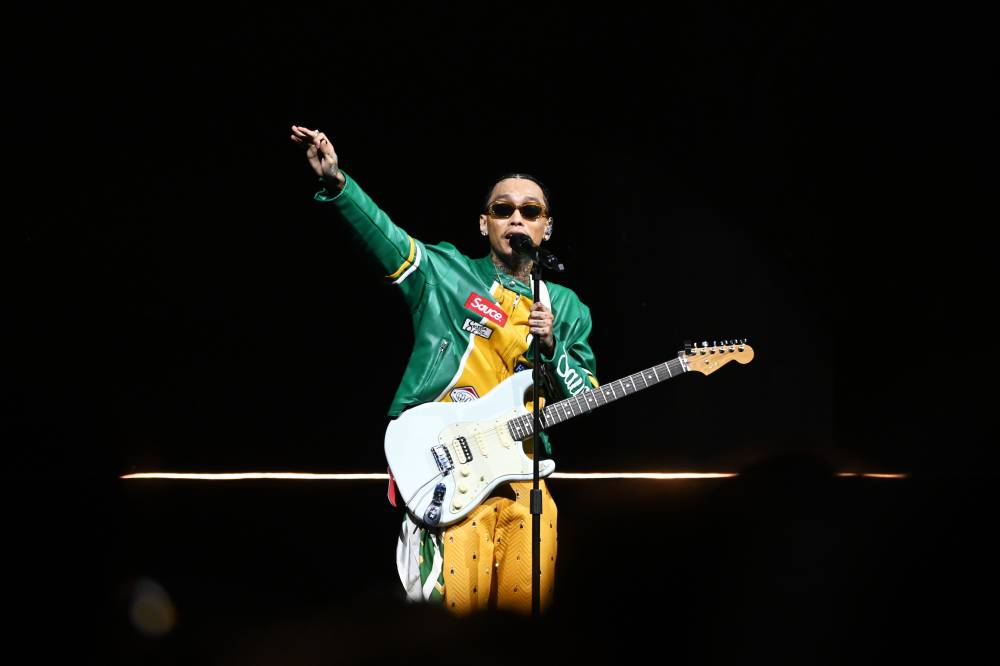

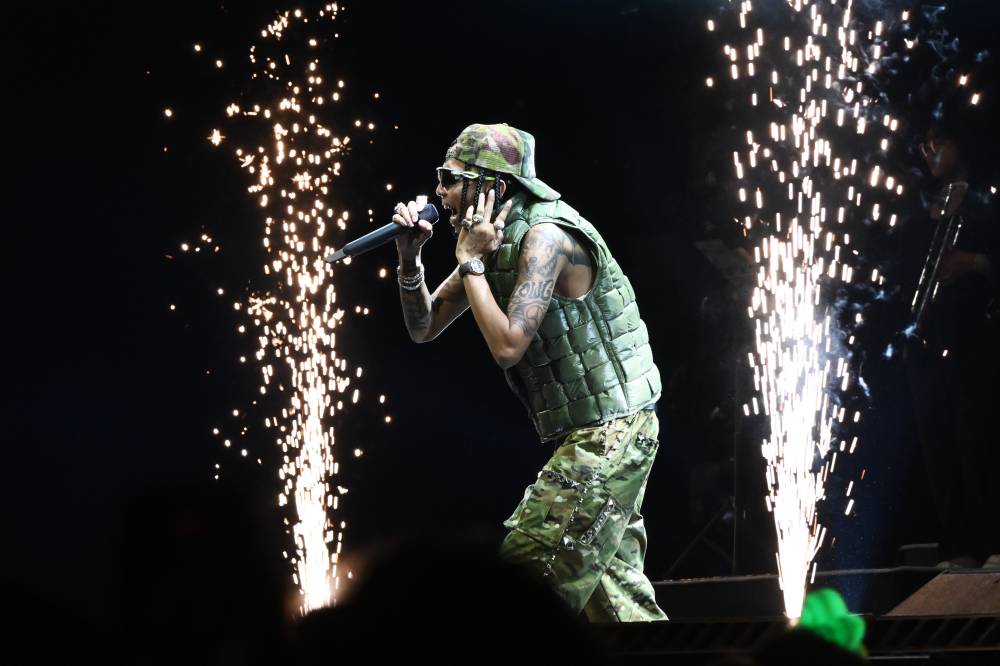

You’ve probably seen the videos by now: Rico Blanco emerging onstage to join SB19 in a rousing performance of his anthem “Liwanag sa Dilim.” And if that wasn’t enough, Blanco—looking like he could’ve passed for a long-lost sixth member—shifted gears, dancing and bringing the house down to the P-pop group’s hit “Dungka.”

At first glance, it seemed like nothing more than a fun little surprise for the 30,000 fans who trooped to the Philippine Arena for the recent Puregold OPM Con. Blanco has always had a flair for the theatrical (just look back at his “Galactik Fiestamatik” era), and he’s actually quite the smooth mover, too (remember that bit of dubstep at the 2010 Myx Music Awards?).

But this rock icon, busting out full-on choreography—hip thrusts and all—next to the ever-explosive Pablo, Stell, Ken, Josh, and Justin? That was something else entirely.

Overly polished

Beneath its novelty, however, the moment could very well be symbolic, cluing us in to a potential shift in attitudes toward P-pop and the gradual embrace of a genre once outright dismissed.

For the longest time, artistic value and respect have been tied to the ethos of rock music—with the guitar-toting, dive bar–touring singer-songwriter as the standard of “real, serious music.” Pop acts, on the other hand—often labeled as shallow or mere conduits of assembly-line music—may top charts, sell millions of albums, or pack arenas, but are still, in the end, found wanting in the eyes of critics.

Scene rivalries have always existed in music: rock fans championed gritty authenticity and live instruments; hip-hop fans claimed street cred; and indie fans scoffed at anything remotely commercial.

It was much the same when the seeds of P-pop as we know it—performance-driven and idol-centric—began to sprout in the early 2010s as an offshoot of the surging Hallyu or Korean Wave. While early adopters found small pockets of support, P-pop in its infancy still lacked a clear identity, making it easy for people to dismiss it as derivative, gimmicky, and cringe-worthy. Not real music.

SB19, and the others who came before and after them, were seen as too polished, too manufactured—as if attention to stylized visuals somehow undermined their artistry. Their embrace of spectacle and displays of affection often invited ridicule and intrusive speculations about their sexuality.

Their mostly young and female fanbase was belittled as irrational or lacking in taste. Their ability to sing live, write songs, or shape their own concepts was routinely questioned. Media and critics were unlikely to give their work serious coverage or appraisal. And when they did, it was often framed as a curiosity rather than a craft.

Making inroads

This is the kind of environment P-pop acts have had—and continue—to navigate. The barometer by which “real music” is measured was never calibrated to accommodate them. So if they were to make it—and if there was to be a future in this space—they had to work twice as hard, contending not just with critiques of their music, but with layers of biases that many of their “more serious” counterparts didn’t have to face.

For girl groups like Bini, the challenge is even more complex—doing all that while walking the tightrope between infantilization and hypersexualization.

But in recent years, through unflagging resolve, creative daring, and exceptional showmanship, SB19 has made significant inroads, taking ownership of the very things they were once mocked for and turning them into tools for innovation. With fan-powered worldbuilding and digital-era discipline, the group has produced well-crafted songs and matching visuals that resonate beyond our shores. They’ve won prestigious awards, shattered streaming records, and redefined what live performances could look like, most notably in the “Simula at Wakas” kickoff concert.

Their success eventually became too obvious to ignore. Slowly but surely, they commanded a second look from the public and even prompted some to reevaluate the genre. That’s not to say everyone doubted SB19’s potential from the start—respected figures like National Artist Ryan Cayabyab, Gary Valenciano, and Ogie Alcasid were among the early believers, openly expressing admiration for the group’s artistry.

Media coverage has grown noticeably more constructive, and institutions like the Ateneo have begun engaging with the genre earnestly, even introducing an elective course on P-pop last year—an academic nod to its growing cultural weight.

A gesture of solidarity

So when Blanco shared the stage with SB19, it felt like an affirmation of this subtle but palpable shift in tides.

Here was a cornerstone of rock stepping into the world SB19 helped shape—and doing something so distinctly pop—at the same venue the group had filled twice over only a month ago. It might be tempting to call it a stamp of approval, but really, it felt more like a gesture of solidarity. A celebration. An act that evoked mutual respect and admiration.

“It’s a dream come true to collaborate with you onstage. Thank you,” Pablo, who had previously recorded “Liwanag sa Dilim” for a television series, told Blanco.

Blanco, meanwhile, thanked the boys for easing his nerves while performing in front of an audience “that deeply loves OPM.”

As their performance of “Dungka” came to a close, Blanco dropped the mic, and Ken, falling to one knee, caught it just as it was about to hit the floor—in a moment that felt lighthearted yet almost reverential.

Some saw it as a symbolic passing of the torch. But here’s the thing: Blanco didn’t telegraph the move, and Ken wasn’t cued to catch it. Which, in hindsight, might be the more fitting metaphor. The baton wasn’t formally handed down—it was anticipated, pursued. And even if it were planned, SB19 still had to work their way up to a place where it was finally within reach.

That moment of recognition and camaraderie wasn’t an isolated one.

The energy surged higher as Bini’s Sheena, G22, and Kaia eventually joined the frenzy in “Dungka.” Bini vibed effortlessly with James Reid on “Secrets,” while Kaia jammed with rock band Mayonnaise on the sing-along anthem “Jopay.” Despite audio issues, G22 powered through “Salamat” with Yeng Constantino.

Stell, Kaia’s Charlotte, and G22’s Alfea blitzed through Bini’s “Shagidi” with razor-sharp moves. Sunkissed Lola swayed the audience with the soft melody of “Pasilyo.” Hip-hop artist Flow G had heads nodding with his fluid delivery on “High Score,” and Skusta Clee’s lush, string-and-horn twist to “Sa Susunod na Lang” added a romantic touch to the night’s varied soundscape.

But beyond individual acts and other surprise collaborations, the concert also offered a glimpse into a broader conversation around P-pop’s identity. If part of the early pushback against the movement was that it felt un-Filipino, what we saw onstage offered a compelling rebuttal.

P-pop has evolved into a movement deeply rooted in Filipino languages, cultural values, and local narratives—take G22’s impassioned performance of the female empowerment anthem “Filipina Queen,” for example. Besides, long-established genres like rock and hip-hop were once foreign imports, too, but were ultimately adapted and redefined by local artists.

If there’s one thing that became increasingly clear as the night wore on, it’s that P-pop—and its cross-pollination with other genres—doesn’t dilute the music scene but makes it all the richer. This affair could very well signal a future where crossovers like these aren’t surprises but the norm.

And perhaps soon, P-pop will be done trying to please or apologizing for taking up space. As SB19 and Blanco might say: “Kung ‘di mo ’to gusto, tumabi ka d’yan!”