When doctors speak and write

When one considers the poet and metaphysician Marjorie Evasco, who has trained medical doctors in writing narratives of healing, one thinks of elegant verse and prose the way they are described by another poet, Darrielle Cresswell:

“And she made elegance

An art form,

For she didn’t just

Place words on her page;

No, she was there

With them,

Dancing,

Eternally dancing…”

At her recent Baguio visit, Evasco conducted a pebble poetry writing workshop for students on a Sunday morning at Mt. Cloud Bookshop, a hub of literary and cultural happenings in the city. Pebble writing seems a more poetic phrase than stating it concerns writing about the environment, climate change, and the like.

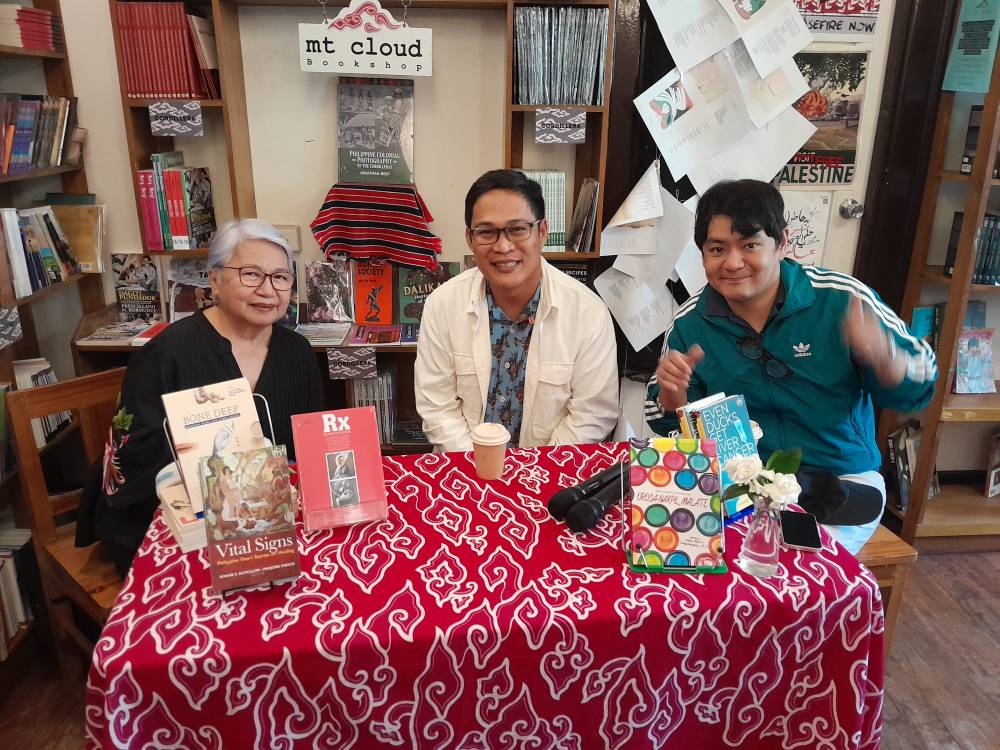

In the afternoon, she led a panel on “The Doctor Is Out: Reseta Talks, Prescribing Narratives” with her physician students, both published authors, Joti Tabula and Will Liangco.

Firstly, Evasco told of how she enjoyed visiting Baguio “where we could talk with writers and readers.” Secondly, she was happy that the subject of the intersection of literature and medicine was being tackled, even though the humanities tended to take the back seat when faced with a medical case. Thirdly, she was there to launch her new Milflores Publishing book, the anthology “Vital Signs: Philippine Short Stories on Healing.”

Short fiction

In the book are short fiction by a gamut of Filipino authors on different forms of healing, including the kind drawn from indigenous knowledge. In a story by Ligaya Fruto published in 1941, she wrote about the lack or absence of abortion services without mentioning the word abortion. As anthology coeditor (her partner here is Dr. Ronnie Baticulon), Evasco pushed hard for the representation of women writers, of writers from the regions in the Visayas and Mindanao.

Tabula defined health not just as the absence of infirmity but also the presence of social, spiritual, and mental well-being, which is frequently not taught in medical school. He saw there was no champion in his profession in making medicine more human. He felt strongly that he needed guidance from the masters in creative writing.

He studied for a master’s degree in the field; he only lacks a thesis to graduate. Meanwhile, he helped set up Alubat Publishing, which specializes in literature and medicine. According to Google, the Tagalog word “alubat” means “to be in a state of extreme danger or peril” or “to be in a critical situation.”

The field of narrative medicine or narratives on healing has grown robustly that doctors even have a literary contest in the field. Evasco holds almost yearly workshops for medical students and doctors. Tabula said there is even a network already called Philippine Society for Literature and Narrative Medicine.

Liangco, author of “Do Ducks Get Liver Cancer?,” said he began writing blogs in, of all Internet spaces, Friendster, with a captive audience of one or two persons, all his friends. He was a student then who discovered that what doctors dealt with in the hospital were not always life-and-death situations. “We are not always saving lives. What we’re doing is a lot of paperwork, we quarrel among ourselves, etcetera.”

Blogging as release

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, he realized that there was poverty in the kind of training he received. He continued blogging “after a hard day’s work to document how I feel, how I interacted with people, handled different cases, dealt with other doctors. Hopefully, I can write every day.”

Tabula, a poet also in Filipino, said nothing beats “writing and reading. You have to do it well. I happened to have read well in high school. Consequentially, I wrote well. In medical school, there were lots of readings, and we wrote a lot on the charts.”

He added that medicine required a writer’s imagination in evaluating different diseases, especially if they’re occurring in a person at the same time. And then, the doctor must have the right amount of empathy “to help the patient search for purpose at the end of life.”

He said “reflective writing” is part of the medical discipline, a “must” for doctors, but it is not done well enough in the Philippines.

Tabula said he felt sorry that after second year college, medical students are not exposed to humanities subjects anymore but focus on anatomy, biochemistry, pathology, and the like. He espoused the integration of narrative medicine to help raise the emotional quotient of doctors.

What sets apart graduates of the University of the Philippines College of Medicine is “you become a builder. You just don’t graduate and get a job,” he said.