When music became a battlefield

War came to the Philippine Commonwealth in December 1941, with Manila and the military installations in the north bombed by Japanese fighter planes hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was the darkest Christmas in living memory. Filipino and American forces retreated to the south. Bataan fell in April 1942, Corregidor in May.

And the Japanese stranglehold on Manila and the rest of the country began.

One of the things that the Japanese military authorities wanted to change in the fallen capital was her culture and music. This was according to National Artist for Music Ramon P. Santos in a recent lecture at Ayala Museum titled “Philippine Music During the Japanese Occupation: A Disrupted Evolution of a New Artistic Language and National Identity.”

The lecture was organized by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Filipinas Heritage Library.

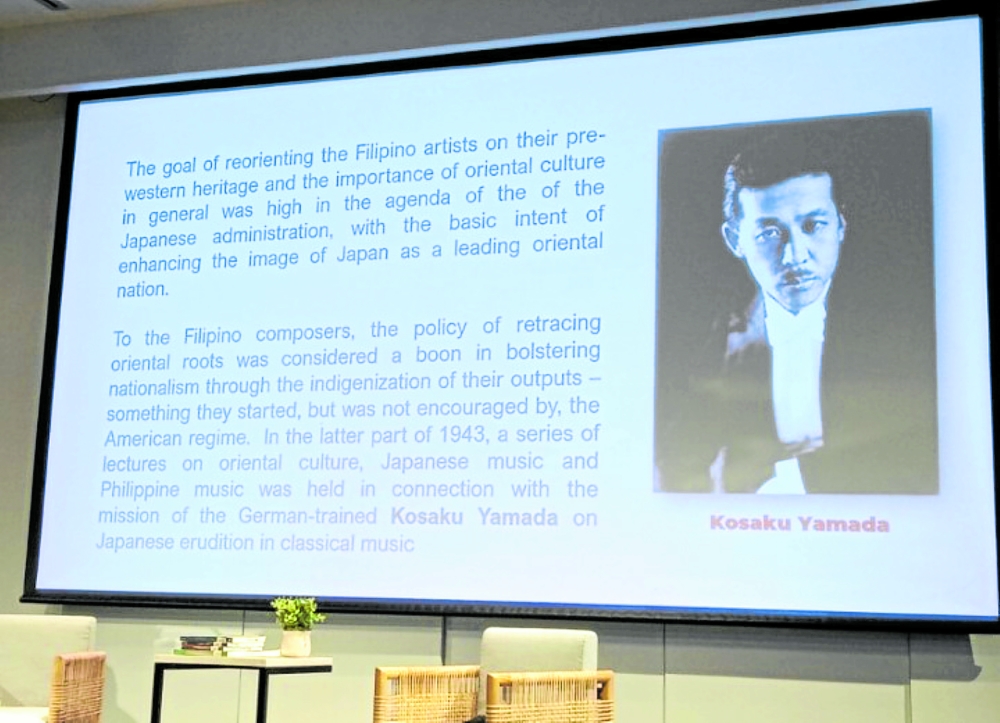

“The goal of reorienting the Filipino artists on their pre-Western heritage and the importance of Oriental culture in general was high on the agenda of the Japanese administration,” Santos said. The intent was to project Japan as a leading Oriental nation, do away with Anglo American influence, and revive pre-Spanish cultural practices, especially those that adhered to the moral code of Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Indoctrination

By 1943, there was a series of lectures on Oriental culture, Japanese music and also Philippine music, conducted by German-trained Kosaku Yamada, a specialist on Japanese classical music, and his team.

Two types of musical works were encouraged, either as commissioned pieces or competition entries: works that extolled the ideals of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, or compositions written for specific events or sectors of society.

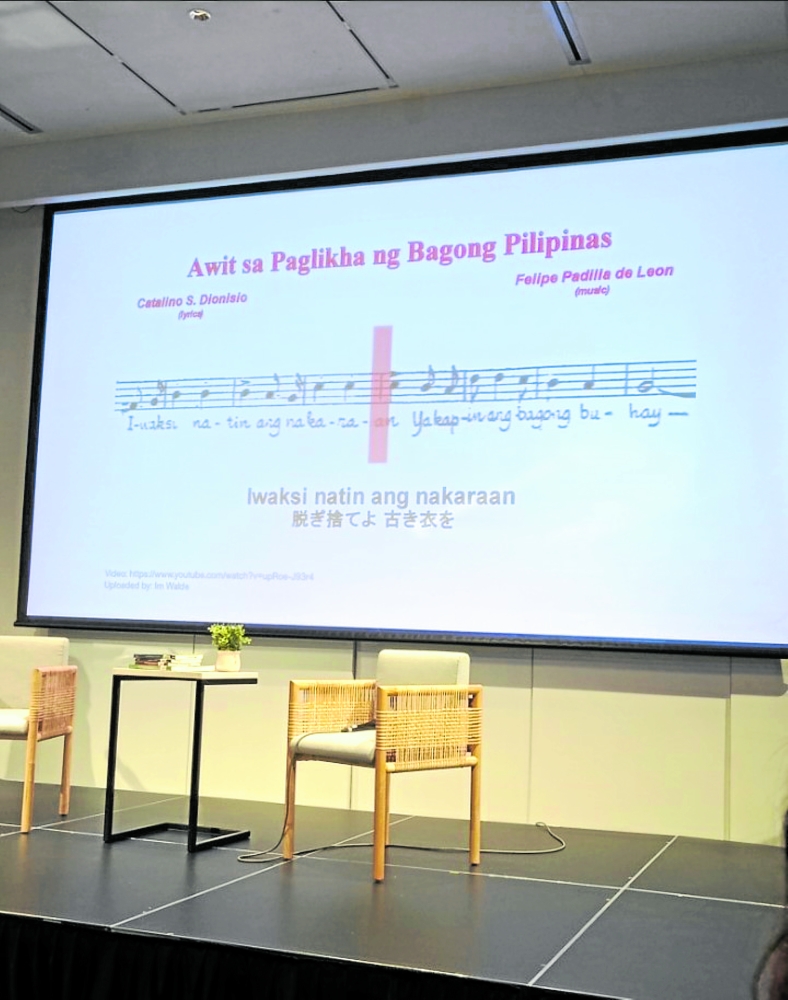

Felipe Padilla de Leon produced “Awit ng Bagong Pilipinas,” “Tayo’y Magtanim,” “Awit ng Magsasaka” and “Awit ng Magdaragat.” Lucio D. San Pedro composed “President Laurel March,” “Stabat Mater,” and “Misa Clemente” while Francisco Santiago created “Magkapit-Bahay Martsa.”

“Much of the music composed between 1942 to 1944 were short pieces for solo voice like Antonio Molina’s ‘Sampaguita’ and ‘Awit ni Maria Clara’; Hilarion Rubio’s ‘Mutya ng Silangan’ and San Pedro’s famous ‘Sa Ugoy ng Duyan,’” Santos said.

Working under a handicap, the Filipino composers and lyricists, the lecturer said, “were still able to articulate nationalist sentiments, by grafting quotations of meaningful melodic motifs in their works.” He gave as examples De Leon’s “Awit sa Paglikha ng Bagong Filipinas” and San Pedro’s “Martsa ng Bagong Pilipinas.”

Ineffectual teaching

The composers at first welcomed the policy of retracing Oriental roots, as this was seen as a nationalistic move to indigenize their works, a development started during the American period but not encouraged by the authorities. However, the program was highly ineffectual, according to Santos. He cited the following reasons: No serious research on indigenous music; very little data on Philippine folk music except for the preliminary writings of Norberto Romualdez and Francisco Santiago; information on the music of Asia hardly existed, and the music of Japan that Yamada and his team introduced was “crudely crafted.”

In February 1945, the Americans finally returned. American bombers and rampaging Japanese soldiers destroyed the southern districts of the city, including Ermita, the family’s birthplace for 100 years. Manila was liberated at last, but at great cost.

After the war, freed from the Japanese yoke, the Filipino composers created large-scale works like Antonino Buenaventura’s “Mindanao Sketches,” and “Youth Symphonic Poem”; De Leon’s “Bataan” and “Banyuhay”; “Hope and Ambition” by San Pedro, and “The Last Trail” by Ramon Tapales.

In the Q&A after the lecture, Santos was asked: Did the Filipino composers work under duress? Did they have a choice? “They didn’t have a choice, I guess,” he replied.