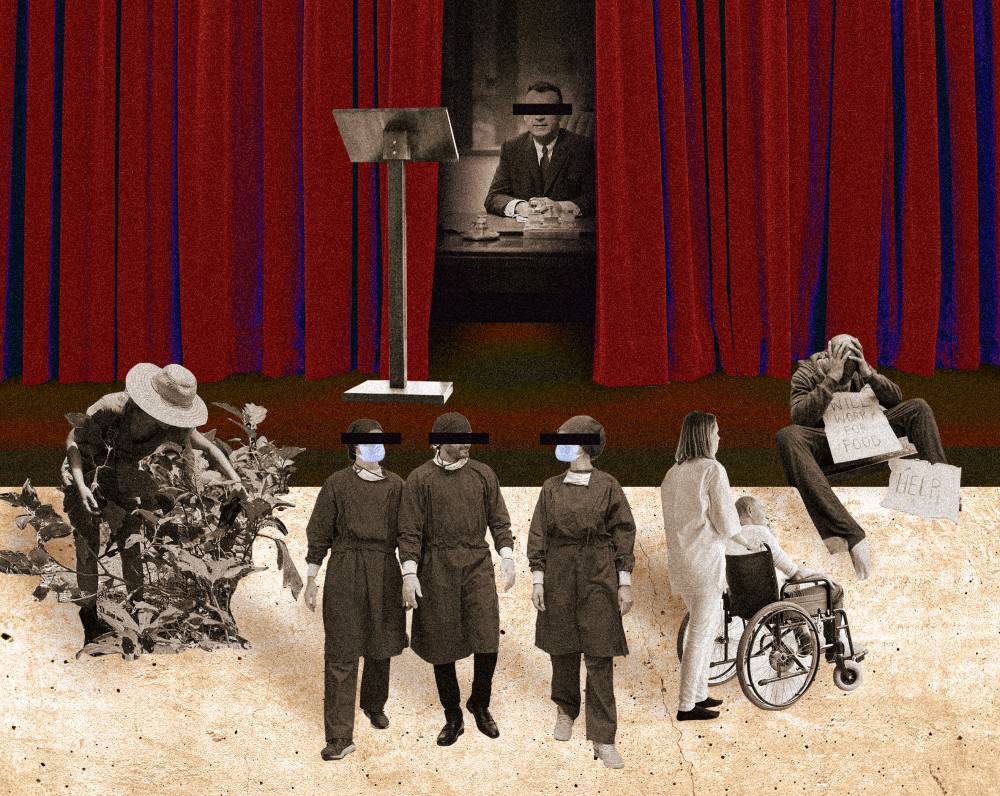

When running the government is easier than making an honest living

Education, more than a right of every Filipino citizen, has long been regarded as an investment for the future. A good education supposedly guarantees high-value jobs, higher salaries, and a better quality of life. But as far as investments go, from increased tuition fees to salaries that don’t quite match the rising costs of living, the return on investment (ROI) has been widely inconsistent.

A college student is expected to spend around P50,000 to P100,000 per year on tuition fees alone. Adding daily expenses (food, transportation, and housing) and other miscellaneous fees—whether you’re at a “big four” school or a state university—spending hundreds of thousands to millions of pesos on a tertiary education is the norm. What more if we add everything spent from grade school to high school? What if we’re talking about someone who pursued post-graduate studies?

And while these aren’t complaints, especially for those intending to become lawyers, doctors, or pilots—where increased costs are expected—what about the minimum wage worker who needs a degree to become a cashier? Why place such financial barriers on those who merely seek an honest living? Why expect excellence from the everyman when we have senators and public officials who only carry loud mouths and promises they rarely ever fulfill?

When running the country has lower requirements than an entry-level job, isn’t becoming a public official the most economical career path with low costs and a high ROI?

Public office as the highest honor and responsibility (supposedly)

From mayors and governors to senators and the president, the general qualifications to run for public office are to have the ability to read and write, to be a registered voter, and to be a Filipino resident for a sufficient amount of time.

This, of course, isn’t necessarily negative. After all, access to public service shouldn’t be solely dictated by one’s educational attainment or the amount they have in their bank accounts.

But as Jose Ma. Montelibano, in his opinion piece titled “ABCs of Public Service,” says: “Because the law opens the way for the most ordinary Filipino citizen to serve the public, a more fundamental law demands that they serve well… Yet, the very law that was created to protect Filipino citizens from bad public servants is the least known and applied.”

The bastardization of RA 6713, or the “Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees,” remains proudly on full display.

It mandates political neutrality between elected officials, but reports of allied camps informing policies and Senate votes dominate the headlines. RA 6713 requires a commitment to public interest, and yet the Philippines was rated as highly corrupt, ranking 114th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in 2024.

And while RA 6713 demands that public officials not take on private practices that impair their ability to perform their duty, we’ve literally had a senator who’d disappear for months at a time in preparation for a boxing match.

What’s more, the supposed penalty for breaching the terms of RA 6713 include: a fine equivalent to six months’ salary; a suspension of one year; or the outright removal from office—reactions to such violations mostly entail half-hearted apologies, a forgettable slap on the wrist, or are even ignored entirely.

Meanwhile, regular employees across various industries pass through all kinds of hoops to find employment. And once they do, they are kept to the highest of standards. For what though? A not-so-competitive salary that can barely (or can’t even cover) their cost of living?

It goes both ways

As much as everything said sounds like a complaint, it really isn’t. It’s a known fact.

It is a fact that private employees have to meet absurdly high qualifications to even get a foot in the door, whereas elected government officials are born inherently qualified. It is also a fact that the everyday salaryman is held to a much higher standard than a mayor or senator (think NBI clearances, barangay cedulas, and drug tests), whereas a public office, by virtue, should be held to excellence.

This isn’t a question of magically raising salaries or lowering expectations for worker performance or attendance—but rather, a demand to make it make sense.

Filipinos, for all that is said about our resilience and strength, are hardworking people. A Filipino will work hard, move to a different country, and take on multiple jobs for the sake of their families. But when those expected to lead cannot even be held to the same standards as their constituents, why put trust in governance? It’s every person for themselves here anyway.